Courage is rare. True humility is even rarer. But the only British soldier to be awarded the Victoria Cross in Afghanistan has both

Beware of imitations, but the words of Lance Corporal Joshua Leakey were the real thing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To listen to Lance Corporal Joshua Leakey on Thursday’s edition of the Today programme, talking about the circumstances that led to him being awarded the Victoria Cross, was to be ushered into the presence of what, in modern-day public life, is a fairly unusual figure: the man without an agenda. Leakey turned out to have exposed himself to Taliban fire on several occasions, manned a machine-gun and, despite his subordinate rank, demonstrated sufficient leadership qualities to turn the tide of battle, and yet his account of these exploits was distinguished by an extreme self-deprecation.

Naturally, his VC, the only such to be awarded to a British soldier in Afghanistan who survived the conflict, was “an honour” and “massively humbling”. But the decoration was, he insisted, “not about me in particular”. It also belonged to his comrades and, above all, would keep green the memory of the two among their number who had failed to come back from the campaign. In a statement reproduced in several newspapers, Leakey observed that “the only thing I was really scared of was letting my cap badge down… I’m lucky. I’m here. I’ve got all my limbs, my health. I’ve got my friends and my family.”

In a media scrum otherwise dominated by senior politicians apologising for just how gamely they had reacted to the rattle of the swill bucket, all this struck a note of genuine humility. Curiously, of all the human activities calculated to produce these feelings of self-abnegation, military valour must rank fairly high on the list. Researching a book about the Bright Young People, for example, that motley collection of social butterflies satirised in Evelyn Waugh’s early novels, I was struck not only by what “good wars” the majority of these gilded young men seemed to have enjoyed, but their determination not to brag about their adventures.

James Lees-Milne’s wartime diaries, for example, record a meeting with an old friend named Hamish Erskine, or, to give him his full title, the Honourable Hamish St Clair Erskine, former boyfriend of Nancy Mitford, fancy-dress party fixture, and, at any rate in the 1920s, the most consummate flibbertigibbet ever to grace the dance floor of a small-hours Mayfair nightclub. Erskine, severely wounded and awarded a Military Cross after being dragged away from the battlefield by a non-commissioned officer, remained tight-lipped. “He denied that he was courageous,” Lees-Milne noted. “There was no alternative to what he had to do.”

What might be called the psychology of humility has a number of different compartments. Some of it is to do with straightforward shyness. A much more significant strand proceeds out of the need for self-effacement, a belief that individual achievements, and the individual will, do not, in the end, amount to very much and that humanity’s ends are much better served by way of selflessness. And yet, of all the human virtues, none, it might be argued, is quite so susceptible to being turned into a parody of itself, and of producing the reverse effect of what is officially intended, such as that very common type, the person who is so determined that a fuss should not be made about him, or her, that an even worse fuss gets stoked instantly into being.

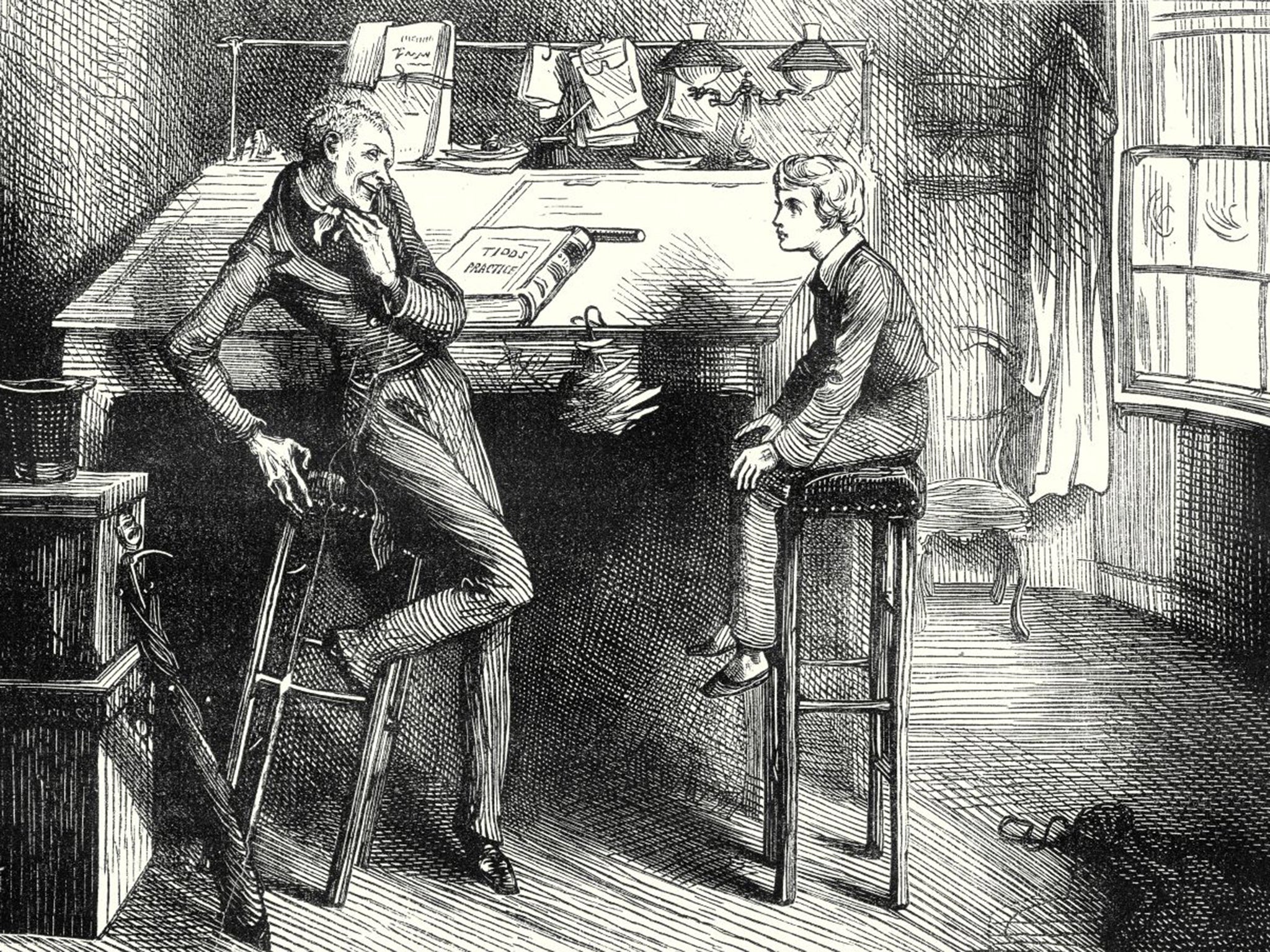

Naturally, the ease with which humility can morph into mock-humility is a creative writer’s staple. Uriah Heep’s constant assurance to David Copperfield of how very humble he is, while secretly plotting to bankrupt his employer and carry off his lissom daughter, wouldn’t fool a five-year-old, but in fact Dickens provides a much subtler portrait of mock self-deprecation in Martin Chuzzlewit’s Mr Pecksniff, a self-aggrandising old fraud, whose two daughters are called Charity and Mercy and who is described as warming his hands by the fire as if they were a widow’s hands or an orphan’s. King Lear, if it comes to it, is a play about mock humility, whose theme, as Orwell once put it, is that if you want to live for others then you should genuinely live for others rather than as a roundabout way of obtaining advantage for yourself.

Dickens, of course, would have been vastly amused by the large number of 21st-century public figures who are encouraged to parade their humility on television or in newspaper columns, for the sentiments being advertised are so obviously ambiguous. If, on the one hand, the banker hauled up before the Public Accounts Committee knows that he is expected to apologise for something, and generally to abase himself before Margaret Hodge and her cohorts, then, on the other, there is always a dreadful sense of his not quite knowing what the apology is for. One could see this in the public dressing-downs administered a few years back to Barclays’ Bob Diamond, whose face, throughout these serial exposures, bore the bewildered expression of a man who couldn’t quite understand why he was being arraigned for trying to do what he thought was his job. And one could see it again in Sir Malcolm Rifkind’s expostulations that his touting for highly paid consultancy work was entirely above board.

What happened to humility? Did it merely go the same way of those other high-Victorian abstractions such as chastity, piety, civility and charity, all of which are struggling to survive in the modern world? Undoubtedly, the decline of religious belief – at any rate in the West – did something to tarnish its attractions, for if there is one thing that an educated European consumer dislikes it is the assumption that there is some motivating force beyond the fulfilment of the individual’s material needs, and the existence of some greater authority than sheer self-interest. On the other hand, even the most committed humanist ought to be able to see the advantages of humility, for at its heart lies an ability to see yourself in context, sub specie aeternitatis, to use that old Latin phrase, adrift in a universe where the richest City Croesus who ever swindled a pension fund is not much more than a glorified worker ant.

That this is not, in the end, a merely abstract discussion was confirmed by another of last week’s news stories, the results of a survey of more than 10,000 14- and 15-year-olds by Birmingham University’s Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues. One of its conclusions was that a focus on exams had squeezed out attempts to instil moral values and that students “appeared to approach moral dilemmas from a self-interest perspective rather than deciding to do what was morally right”. Around half of those surveyed “failed to identify good moral judgements”.

How does one guard against the “self-interest perspective”? Why, by being humble. And what role models exist to encourage this humility? Trying to think of a modern politician who might be described as “humble”, I could come up only with the Labour Party’s deeply ascetic Frank Field, who, back in 1997, was invited to “think the unthinkable” by Tony Blair at the Department of Social Security and sacked for doing exactly that. The Pope, with his lack of interest in Vatican ceremony and his keenness on cheap hotels, ticks certain of these boxes while failing to disguise a suspicion that genuine humility is rarely quite so media friendly. In the arts world, the best example I could find was the musician Robert Wyatt, confined to a wheelchair these past 40 years but who, I learn from Marcus O’Dair’s excellent biography, Different Every Time, declines to distinguish between his pre- and post-paralytic state. Unfortunately, such people rarely go on to head governments or control investment funds. Perhaps they should.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments