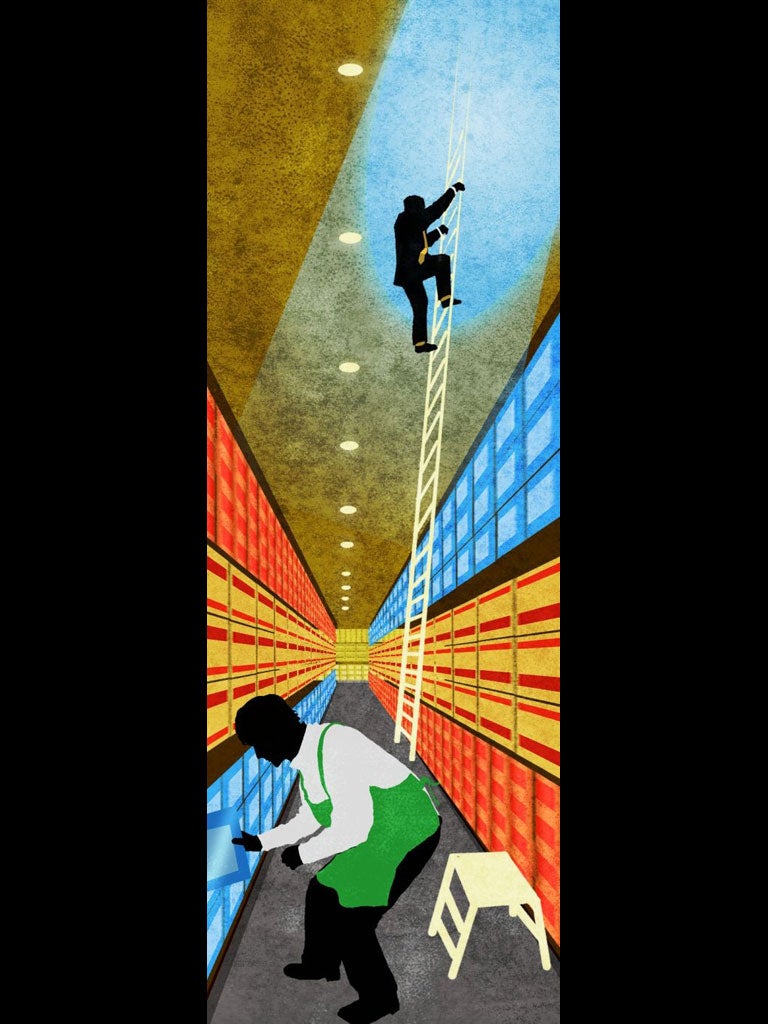

Viv Groskop: Poundland may not be a dream job – but it doesn't have to define you

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Shelf-stacking was too challenging for me.

This was around the late 1980s, early 1990s, and I was in the sixth form and earning money for driving lessons. The problem was, I was an overzealous stacker, eager to please and wanting to save my co-workers the extra graft of having to restack later. "You're packing too many in," tutted the manager. "No one wants to buy crushed crisps, Vivienne." I was stripped of my responsibilities regarding the Golden Wonder delivery.

They moved me to the till. Even more disastrous. I liked to chat to the customers more than I liked to add up their grocery purchases correctly. This was in the days before scanning, where you keyed in each price individually. I can still remember the resentment in one woman's eyes. I rang through her entire basket of goods twice as she thought I'd overcharged her. Which I had. But we had had a great chat! For free! What was her problem?

Hopeless doesn't cover it. But this is the trouble with work. We are all made for different things in life. But sometimes it's not easy to find those things. And sometimes no one wants to pay you to do the thing you would rather be doing – or even just the thing you would be better at.

At the same time, certain kinds of work are seen as exciting and worthwhile. Others are euphemistically referred to by prime ministers as "learning experiences". Honestly, who wants to sign up to a "learning experience"? It has the ring of Deliverance or at least of mild torture of some kind.

The discussion about work has arisen thanks to the Government's various new unemployment strategies. In the past few weeks TK Maxx, Poundland, Sainsbury's and Waterstones have all sought to distance themselves from these schemes. And yesterday the Employment minister, Chris Grayling, found himself having to explain to BBC Radio 4's Evan Davis that David Cameron really does have a point about this "learning" in a supermarket business.

It's not much fun to hear it from an Old Etonian who has never strained his eyes checking a sell-by date (tell me about it – the effort!), but it is true that you can actually learn something from shelf-stacking. Even if, as in my case, it's just that you shouldn't really be doing it. (Davis seemed strongly to disagree. With Grayling. Not about whether I would be better suited to shelf-stacking. Unhelpfully, this was not discussed.)

But the arguments over the rights and wrongs of these schemes underline how messed up we are over work as a concept. Most people now seem to labour under the illusion that fulfilling, meaningful work is a basic human right. We wish. Unfortunately, it's a massive luxury. And one few of us can afford, especially in a recession, where it's monumentally unwise to be picky about how you earn your cash.

It's almost as if "work" itself has become exclusively an abstract concept, something we engage in as a route towards self-fulfilment, a part of our identity. In our collective mind, it's no longer something we do to pass the time and earn money to pay the rent. But that definition of work is just in our minds. The reality is very different. Most people have at some stage in their life worked in low-paid, low-skilled jobs in supermarkets, bars, restaurants, factories or on the land. And many – actually, surely, most? – do it for a living their whole lives.

The idea that you can turn something exciting that you love to do into your main source of income is a relatively modern one. Traditionally, work has been something you did to get by. If you can make it more than that? Well, in that case, as my grandad would have said, you don't know you're born. He ran a corner shop for 40 years. He saw it as a job to be tolerated, not a vocation to lose himself in. He was bemused by ineptitude around point-of-sale displays.

We assume that there's something wrong with "working to live". But the fact is, that is what most people do. Only one thing is for sure: one way or another, we all have to work because we all need to earn money to live. Anything else is a bonus, according to Sylvia Plath: "You don't write to support yourself. You work to support your writing." (If Plath, not the most practical of people, could embrace that, then surely anyone can.)

The difficulty comes when it feels as if someone else is exploiting your situation. The Government's problem is that the "work-for-free at Tesco" row is about two completely different things which have become dangerously conflated. First, we have a group of people on benefits who have not necessarily ever seen anyone in their family go out to work, and who have no idea what the point is of working when you can't get paid much more for working than you do for being on benefits. Second, we have an unemployment problem because there are not enough jobs to go round.

It's the second problem that is the killer here. If you have jobs going and money to pay people to do them, could you please just employ people and pay them? There is no need to call it "work experience" if it is "work". The first problem is a longer-term one and will not be solved by telling those used to benefits, "Oh, you have to work at Tesco now to get the same money you used to get for free."

Meanwhile, let's not disrespect work of any kind. Work is work and, more importantly, it's money. Whether you stay in it or move on, it's not who you are. Royal Bank of Scotland boss Stephen Hester started out packing Polos. Damien Hirst first discovered formaldehyde when he drew the short straw with a student placement at a mortuary. Shirley Bassey worked in a porcelain factory. Janet Street-Porter worked at Woolworth's. Sue Perkins was a toilet cleaner.

I was and always will be a person who cannot stomach Golden Wonder crisps. They're always crushed into little bits anyway, aren't they?

twitter.com/VivGroskop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments