Rupert Cornwell: The mother who blazed a trail for Obama's career

Out of America: Stanley Ann Dunham was, as the title of a new biography attests, a very singular woman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mothers of American presidents can be unusual. Virginia Kelley, whose first born was Bill Clinton, was a lively soul from deepest Arkansas with a penchant for men, racehorses and make-up. Or take Lillian Carter, the mother of Jimmy: nurse and Peace Corps volunteer, a daughter of the Deep South who put desegregation into practice long before civil rights took wing. But none surely is as remarkable as Stanley Ann Dunham.

Ponder Barack Obama's background and you think of the most exotic part, his brilliant and dominating Kenyan father, virtually unknown to the son, who would inspire Obama's memoir Dreams from My Father. Then there's his maternal grandmother – "a rock of stability throughout my life," the future president wrote in his political manifesto, The Audacity of Hope – who died on the eve of his election in November 2008.

Of his mother, however, we were long given little encouragement to learn more. She came from Kansas, Obama said in his campaign, using Kansas as shorthand for American normality. In her case, though, nothing could be further from the truth. At last, in a fascinating and overdue biography by Janny Scott, Stanley Ann's story has now been told.

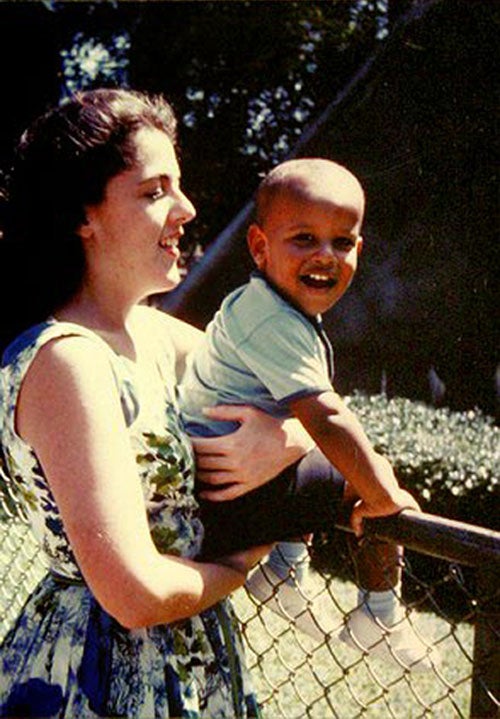

A Singular Woman is the title – and singular she was, starting with her first name, taken from her father: "He wanted a boy, and he got me," she would joke. To describe her as a white woman from Kansas, Scott writes, is like describing her son as a politician who's keen on golf. In fact, Kansas barely featured. By the time she was two, the family had moved to California – then back to Kansas, then Oklahoma, Texas, Seattle and Hawaii.

There she went to school and university, and met Barack Obama Sr in autumn 1960, when she was 17. When she became pregnant, they married, and on 4 August 1961, Barack entered this world in a Honolulu hospital, a fact proven by the world's most famous birth certificate.

By the standards of her or any other time, she was a trailblazer. Stanley Ann Dunham married an African when mixed marriages were illegal in half of all US states. Divorced, she remarried and completed her undergraduate degree, then moved with her new husband, Lolo Soetoro, to Indonesia – which in the 1960s might have been the dark side of the moon for almost every American.

There she would spend more than half her adult life. With Soetoro, she had a daughter, Maya, and for long periods was raising not one, but two mixed-race children, of different fathers, virtually singlehandedly. She spent countless early-morning and evening hours educating her son herself. When she felt she could do no more, she sent him back to Honolulu, where he lived with his grandparents.

In 1972, she went back to Hawaii to be with young Barack and embark on a postgraduate degree in anthropology. Three years later, she returned to Indonesia to do the fieldwork for the degree. This time, though, her son did not accompany her.

Stanley Ann's second marriage lasted longer, but was effectively over by the late 1970s. She would become a top development economist, a fighter for women's rights, and a champion of micro-credit to help the rural poor in Java. In 1992, she returned to the US, spurred by the marriage of her son. By 1994, she was back in Indonesia, but her health was failing. In 1995, she left Jakarta for the last time, and 10 months later, at 52, died of uterine and ovarian cancer.

You can see why Obama did not dwell on much of this. His mother was his certificate as a regular guy – except regular guys' mothers don't live abroad, look like peaceniks and specialise in foreign aid. But, through her own great-great-grandfather, one Falmouth Kearney who came over in 1850 during the potato famine, Stanley Ann did give him what no self-respecting president should be without: Irish forebears and an ancestral hometown (Moneygall, south-west of Dublin) to drop by when he visits Britain and Ireland in nine days' time.

A Singular Woman is not a sentimental book. When Stanley Ann died, Barack was still a civil rights attorney and law professor in Chicago, not yet elected to the Illinois state legislature. But she suspected what might happen. In Indonesia, she would boast about her evidently extremely gifted son, telling a friend that he could be the first black president. Independent-spirited and ever curious, she loved Indonesia and its people, and had none of the stereotypical arrogance of the American abroad. But when the chips were down, she knew her son's destiny was in the US.

In a moving passage, Obama talks to Scott of his mother, her values and idealism, which verged sometimes on naivety. She was concerned about the big things in life – less so about the nitty gritty; whether, for instance, a job carried health insurance.

Where she was passionate, he is dispassionate – but maybe the cool also reflects Indonesia, where politeness and outward good temper are ingrained. And Obama over the years has grown readier to acknowledge her influence.

Dreams from My Father first appeared before her death. In the 2004 edition, he adds in a new foreword that, had he known his mother would die, he might have written a different book, "less a meditation on the absent parent, more a celebration of the one who was the single constant in my life".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments