Rupert Cornwell: Obama will be on trial with the 9/11 accused

Out of America: President's decision could rebound. US courts are not used to defendants who've been tortured

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At the time, as America reeled from the horror of the 11 September attacks, the idea seemed perfect: a remote and instantly available high-security prison for the country's most implacable enemies – "the worst of the worst", as the Pentagon boss Donald Rumsfeld called them, when the place opened for business in January 2002.

Technically it wasn't on US soil, so inmates would not enjoy the tiresome protections of the American legal system, nor, since they were not classed as prisoners of war, those "quaint" Geneva Conventions. It was conveniently close to the mainland, but hidden within a military base, so prying eyes could be kept away.

But Guantanamo Bay hasn't quite worked out like that. Instead, it has proved a nightmare, and not just for the numerous detainees who, far from being "the worst of the worst", were mere flotsam from the Afghan battlefield. Such was the blot on America's global reputation, and so uncomfortable the legal arguments that Guantanamo spawned, that even president George Bush wanted to shut the place down, only to conclude it simply wasn't practical.

Last 23 January, three days after taking office, Barack Obama signed an order to close Guantanamo within a year, but found himself facing the same realities as his predecessor. The deadline will not be met, and last week Gregory Craig, the White House counsel closely involved in the deliberations, in effect paid for the delay with his job. But the 44th president's Guantanamo travails are far from over.

From the outset, the US authorities faced the problem of what do with the captives. Even in Guantanamo, they couldn't be held for ever without trial of some kind. So military tribunals were set up, but their loose standards of evidence and the limited representation permitted to defendants served only to draw more criticism.

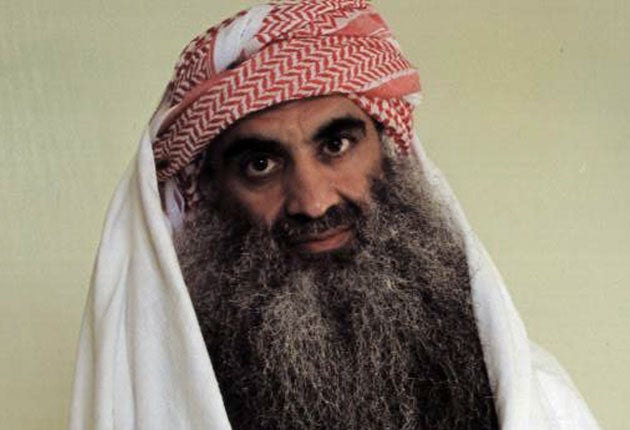

The Obama White House sought to amend the tribunals' mechanism, but with limited success. Now it has gone a giant step further, with the stunning news that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four other prime organisers of 9/11 will be taken to New York, the scene of their crime, where they will be tried in a civilian federal court a few blocks from Ground Zero, where 2,605 people died.

There could be no clearer proof that Obama means to get rid of the shameful limbo-land that is Guantanamo Bay. It is the boldest decision yet taken by this President – but could also turn out his most foolish.

If the trials proceed smoothly, they will be a belated vindication of the American legal system. They will make a political point, too, further distancing this administration from the Bush-Cheney creed of government by executive fiat. But if they do not proceed smoothly?

The trial of Zacarias Moussaoui in a federal court in Virginia gives a taste of the potential pitfalls. Moussaoui, the so-called "20th hijacker", pleaded guilty to being party to an al-Qa'ida conspiracy to crash planes into buildings and remains the only person thus far convicted in connection with 9/11. Moussaoui's histrionics, and his long insistence on conducting his own defence, often turned this trial of a comparatively small fish in the war on terror into a circus that lasted four years, from 2002 to 2006. In the end, civilian justice worked, but barely.

The trial of Mohammed and his accomplices (presumably we must now call them "alleged accomplices") is of an entirely different magnitude. The possibilities of legal snarl-ups are endless. For starters, the five may seek a change of venue, on the grounds a fair trial is impossible in New York City. Then there's the torture factor.

During his interrogation in CIA-run "ghost camps", Mohammed was subjected no fewer than 183 times to waterboarding, a procedure that Eric Holder, the US Attorney-General who announced the New York trial on Friday, has publicly declared to be torture. The Bush-era military tribunals admitted hearsay evidence and evidence obtained under duress, but civilian courts do not. So what if Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the entire plot, withdraws his confession? If that is struck from the record, does the US have enough other evidence to prove a death-penalty case? If it does, how much will have to be heard in camera, for reasons of national security?

And what if the five try to call other suspected terrorists, either at large or behind bars, as witnesses? Of course, Mohammed, who has proudly boasted of his responsibility for the attacks, may try no such manoeuvres. But if he attempts to turn the courtroom into a theatre of martyrdom, the trial would merely fuel new grief, new anger, for the bereaved families.

The timing of the trial is not clear, but it may be in full swing by the time of the mid-term Congressional elections, now less than a year away. If things get bogged down – or, worst of all, if the case against a defendant were thrown out on technical grounds – a political disaster for Obama's Democrats could be in the making. Republicans who are already lambasting the decision to try the five in a civilian court will make hay with charges that Obama is both naive and unpatriotic.

So much, in that case, for good intentions. In the depths of the Second World War, Churchill used to tell colleagues that when the Nazi leaders were caught, they should be put up against a wall and shot. War crimes trials, he claimed, would be a farce. In fact, Nuremberg, for all the complaints of "victors' justice", was a cathartic exercise, showing that the law could cope with such gigantic crimes. New York could yet be another Nuremberg. If not, however, even Barack Obama will have to admit that Churchill had a point.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments