Rupert Cornwell: Magic Johnson still smiles in the face of HIV

Out of America: A TV documentary next weekend and a Broadway show mark the inspirational life of the basketball legend, who retired in 1991

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

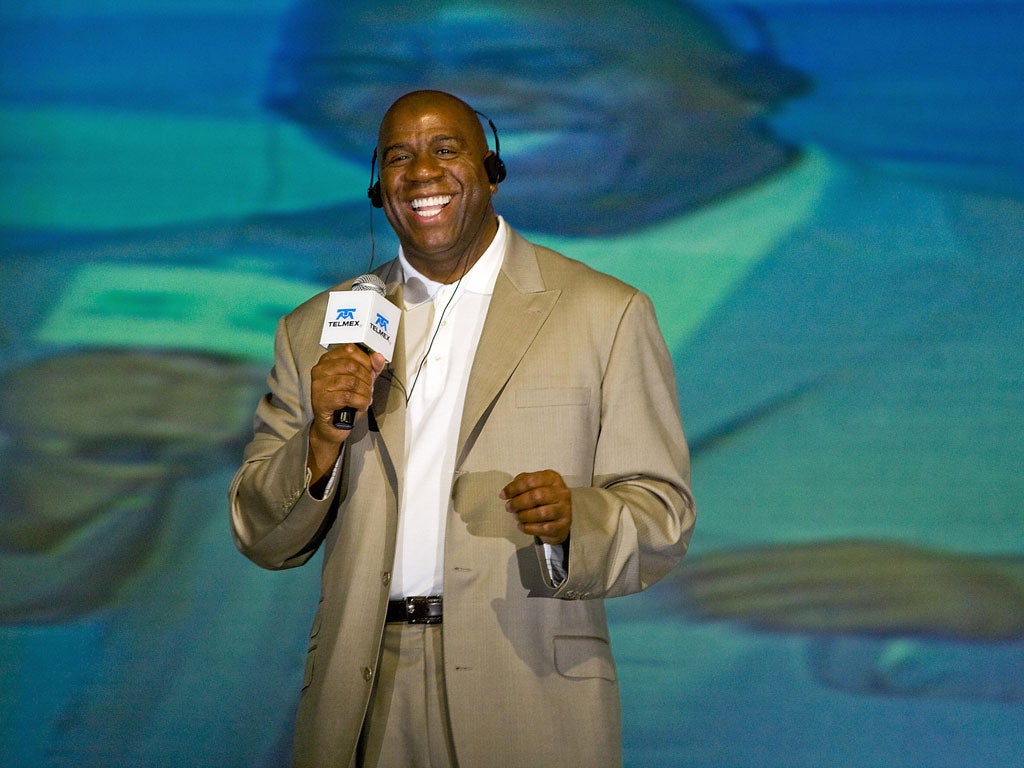

Your support makes all the difference.You didn't have to love basketball to love Earvin "Magic" Johnson. Yes, he was a great player – as good as Michael Jordan, in the view of many qualified to hold forth on such matters. But, above all, it was that smile; that huge, infectious and utterly disarming smile, melting the stoniest of hearts at the very first encounter. As much as his sporting prowess, his smile made him Los Angeles's crown prince, as he led his LA Lakers to five National Basketball Association championships during the 1980s. Today, it is one of the reasons why Magic is one of the most inspirational stories in a country in sore need of them.

But the smile also contributed to disaster. The temptations for idolised superstar athletes who spend so much of their career away from home are well known, and Magic by his own admission succumbed to more than his fair share. In his case, the consequences were calamitous. On 7 November 1991, in a moment many basketball fans met with a stunned disbelief comparable to the JFK assassination, Johnson announced that he had contracted HIV, and was retiring from the NBA immediately.

To understand the shock, you must remember how the world saw Aids back then. The disease was a plague, terrifying and not fully understood. It was associated with homosexuals and drug addicts, and was assumed to be a death sentence. The most famous public faces of Aids were the actor Rock Hudson and the rock star Freddie Mercury, who hid their condition until their gaunt and ravaged appearance made it impossible to deny. Beset by press speculation, Mercury finally confirmed he had the disease on 23 November 1991. A little over 24 hours later, he was dead.

Then there was the tennis champion and civil rights campaigner Arthur Ashe, who in April 1992 announced that he had Aids. Ashe, heterosexual and with the most conventional family life, had apparently been infected by contaminated blood used for a transfusion after heart surgery. Within months, he too was dead, proof that Aids could strike anyone, with equally deadly consequences.

During the Eighties, the Reagan administration had been attacked, and not only by the gay community, for its perceived indifference to what was already clearly a national health crisis. By the time that Magic held his press conference, attitudes were changing, as later demonstrated by the critical and box-office success of the movie Philadelphia, about a gay attorney who is drummed out of a prominent law firm because he has Aids. The attorney, played by Tom Hanks, sues the firm for unfair dismissal and wins. But he too dies of his illness. Aids might no longer be a badge of social shame, the film was saying, but it was no less fatal for that.

Magic, too, encountered prejudice when he went public with his condition, revealed by a routine insurance medical. Although an adoring public voted him into the NBA's All-Star game in February 1992, some players refused to work out with him, claiming they could be infected through a cut. Johnson had hoped to make a comeback, only to realise he could not do so without throwing his sport into chaos. However, he never lost his smile.

Even on that day in 1991, as he told the world of his disease, the smile was on display – as huge, as beaming and as irresistible as ever. That day, Johnson took Aids out of the shadows and became the new face of the disease, hopeful and optimistic. He felt absolutely fine, he declared. "You have to come out swinging and I'm swinging. I'm going to beat it and I'm going to have fun."

At the time, those words seemed absurd bravado. This, everyone believed, was a dead man walking. But everyone was wrong. Contemporaries such as Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston may have gone – but, 20 years on, Magic Johnson is alive and very much thriving.

Not only is he a global ambassador in the struggle against Aids, with a foundation that has raised millions of dollars for research. His business interests, including property, health clubs and a chain of cinemas, are worth some $700m (£438m). He owns a TV channel aimed at promoting the talents of young black actors, and leads a group bidding for the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team, valued at $1bn or more. Johnson is proof that even when infected with HIV, a person can lead a full and productive life.

It should be said that he was fortunate in his timing. By 1991, the mysteries of HIV/Aids were being unlocked, and new drugs were already under development. Today, Johnson takes a cocktail of them. He has not been cured of HIV, but thanks to the drugs his immune system functions normally.

Paradoxically, Johnson's success may have lessened the spotlight on Aids, creating an impression that it has gone the way of smallpox and polio. Far from it. In the US, an estimated 1.2 million people currently have the virus, and since it began to spread in the 1970s, 500,000 may have died from it. Indeed, according to President Barack Obama, in a speech marking World Aids Day last December, while the infection rate in the US overall has been holding steady for more than a decade, among young black gay men it has risen by almost 50 per cent in the past three years.

Globally, even though the rate of increase in new cases each year may have slowed to a virtual standstill, some 34 million people globally remain infected – three-quarters of them in Africa. And that despite the $15bn global Aids relief programme announced by George W Bush in 2003. The plan is not perfect and the follow-through has been patchy, but for a much-vilified president it may prove his most admirable legacy.

If Bush is already half forgotten, Magic Johnson is not. Next weekend, the sports channel ESPN is running a 90-minute documentary on his remarkable story, and in April a show opens on Broadway chronicling his glory years with the Lakers. But no actor surely, however gifted, will ever match that Magic smile.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments