Rupert Cornwell: A 21st-century version of the medieval stocks

Congressional hearings used to be riveting political theatre that could turn US history. That's all changing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

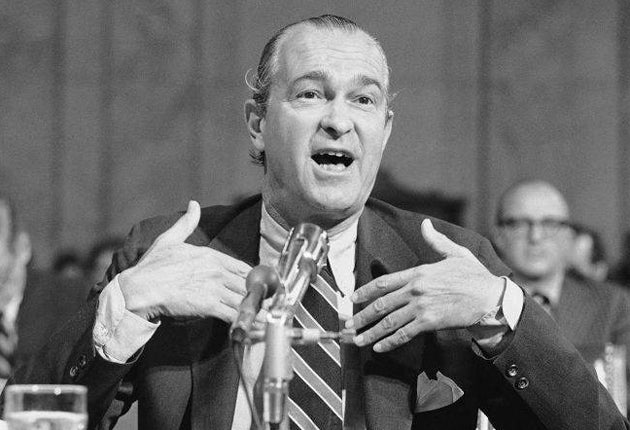

Your support makes all the difference.When he looks back on this annus horribilis for BP, Tony Hayward will doubtless remember yesterday as among the very worst of many dreadful days – the day he was "sliced and diced", as one of his inquisitors put it, under the eyes of the entire world. It will be scant consolation to the oil company's chief executive to know that, whatever his personal discomfort, he is participating in one of the signature rituals of American democracy.

More than any other of its activities, hearings highlight the role of Congress as a separate and co-equal branch of government, utterly independent of the executive and judicial branches, headed by the White House and the Supreme Court respectively. This gives the US legislature a unique authority.

The power of subpoena ensures that if summoned, no ordinary citizen can refuse to appear without risking being charged with contempt of Congress, an offence that can lead to fines and imprisonment. To lie under oath is, if anything, worse – as the former CIA director Richard Helms found out in 1977 when he was fined and given a two-year suspended jail sentence for denying the agency had secretly plotted to bring down the Allende government in Chile.

But the many reports of Mr Hayward's humiliation do not tell the whole story. The fact is, investigative hearings by Congress aren't what they used to be.

Once they were not only riveting political theatre but events that could turn US history. In 1954, hearings destroyed the reputation of the malign Senator Joseph McCarthy. The televised Watergate hearings of 1973 and 1974 helped bring down Richard Nixon, and the Iran-Contra hearings of 1987 almost did the same to Ronald Reagan. That rarely happens now.

This is not to dismiss the backstage investigative work carried out by the Committees: take the unearthing of BP memos suggesting the company was more than aware of the risks of the Deepwater Horizon well. But the acute partisanship of modern US politics increasingly blunts the Committees' thrust.

That became clear at the outset, when the senior Republican on the House Commerce and Energy panel turned his fire not on BP but on the Democratic administration of Barack Obama, accusing it of a "$20bn shakedown" by forcing BP to set up a compensation fund for victims of the spill. The disaster is thus a subplot of November's Congressional mid-term elections.

As a result, yesterday's grilling of Mr Hayward – like those of top executives involved in the 2008 financial collapse and earlier corporate scandals – is a 21st-century version of the medieval stocks, public disgrace for the public villain of the moment. In recent months the heads of Wall Street banks and Toyota's president, Akio Toyoda, among others, have sat where Mr Hayward sat. In varying degrees they apologised to their inquisitors, and by extension all America, for their sins. Mr Hayward did the same.

But for all the venting of outrage, and the emotional satisfaction thus gained, few new facts generally emerge. Those that do are usually lost amid the showboating of committee members.

When, after lengthy opening statements by each member of the panel, the man in the hot seat does get his chance to speak, his best tactic is to grovel. Like Mr Toyoda, Mr Hayward will be reminded that remorse is not enough. But for the cameras and the reporters, a new day and a new story will soon dawn.

Invariably, silence is better than bravado. Alone among his Enron colleagues, former CEO Jeffrey Skilling declined to invoke his right to avoid self-incrimination under the Fifth Amendment during Congressional hearings into the energy giant's collapse in 2001. But his robust self-defence probably gave prosecutors the ammunition with which to convict him. Mr Skilling is now serving a 24-year sentence in a federal prison.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments