Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The American writer Lydia Davis, whose collected stories are about to come out, has a curious reputation among the cognoscenti: some of her stories are shorter than anyone else’s.

Davis translated Proust, and perhaps it was in reaction to that that she started to enjoy the one-sentence short story, the one-clause short story, the short story consisting of fewer than 10 words. My favourite among these very short stories is Away from Home, which reads in its entirety; “It has been so long since she used a metaphor!” – a little masterpiece of regret which anyone who has ever struggled abroad in a non-English speaking environment will recognise.

How short can a short story be? Some of Chekhov’s early sketches are only a page long; some of Kafka’s only reach a cryptic paragraph. In the 20th-century, the challenge of writing a very short story was turned into a challenge, or a competition, or merely a creative writing task. There is a whole genre arising from creative writing classes called “flash fiction”; the idea is that one writes to a set number of words, perhaps 50. Little of any interest has come from this project, and not many writers, having essayed it, have taken it all that seriously. There is an apocryphal story of Hemingway producing a six-word story running For sale: baby shoes, never worn, but if he did write it, he never published it.

A French writer once apologised for the length of a letter, saying that he hadn’t had the time to make it shorter. And some writers have genuinely found there was nothing more to say after a sentence. Before I read Lydia Davis, I thought the shortest story written and published with literary intent was by Augusto Monterroso: When he woke up, the dinosaur was still there. (Seven words in Spanish). Davis outdoes him with her story Example of the Continuing Past Tense in a Hotel Room: “Your housekeeper has been Shelly". The very shortest, I think, is the alarming “Index Entry”, which speaks quite eloquently of someone taking the wrong side in Pascal’s Wager, and finding out when the sentence of his or her life is so abruptly interrupted that they may have made a terrible mistake. It runs: Christian, I’m not a.

Writing, and particularly the writing of a short story, is always a balancing act between the suggestive and the specific. Too much of the one, and the story could mean anything at all – “I love you” is not a story. Too much specificity and worked out implication, and it is a novel rather than a short story. Oddly, these super-short stories, which have spread in an age of lowering attention spans and 140-character summaries of emotional states, often seem quite different in intent; Lydia Davis’s 10-word stories require a very slow reader, like the interpreter of crossword clues. It is hard not to read them and wonder what is none of our business: how long they took to write.

Those who know Peter call him by his real name

Lord Mandelson is evidently enjoying himself hugely with the publication of his memoirs – come on, those pantomime-villain TV adverts are funny, aren’t they? Unusually, it looks as if they may be required reading (I certainly enjoyed the book). Johnny de Falbe at John Sandoe’s bookshop told me the other day that the phone was ringing with constant requests for the volume. Could it be that the British reading public is learning to love Peter Mandelson, too?

Not quite. I notice that surprisingly often, when Mandelson is referred to in print, he will casually be referred to as “Mandy”. Newspapers are always inventing nicknames for politicians which no one in the political sphere would ever recognise. In the eighties, no one within the loosest orbit of Mrs Thatcher would ever have referred to her as “Maggie”, let alone addressed her as such; she was always “Margaret” to anyone with a claim to insider status. But there is something rather nastier about the persistence of “Mandy” as a nickname for Lord Mandelson. He doesn’t in the least look like someone who encourages his closest friends to call him by a girl’s name. As it is, the tabloids, harping on endlessly in their tittering suburban way, look very much like playground bullies hinting menacingly that they might let out a secret. They may have forgotten that it was all clarified many years ago. If you want to pretend you know him, call him “Peter”.

Those pubescent shrieks will always be with us

“What’s going on?” I said. Round the back of a Shaftesbury Avenue theatre, a huge crowd of teenage girls gathered, lightly interspersed with some pained-looking mums and a few middle-aged men of deeply worrying appearance. From time to time Mexican waves broke out, and shrill choruses of shrieking; the girls’ eyes were bright and their elbows being sharpened.

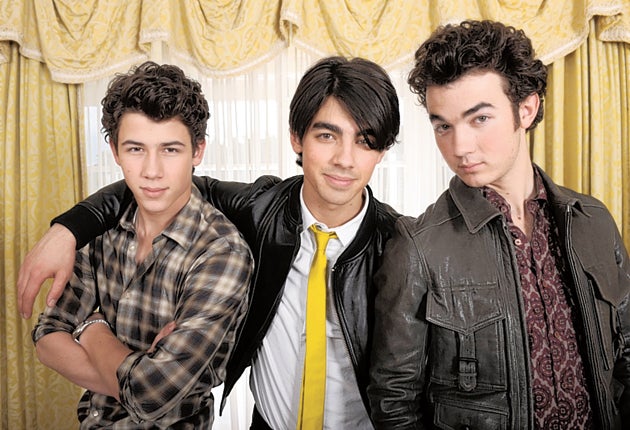

“It’s Nick Jonas,” it was explained to me. “Who?” I said. “Nick Jonas,” the girl said, rolling her eyes. Despite my being an avid reader of Heat magazine, this particular teen idol had completely passed me by. I discover that he formed a band with his brothers, called the Jonas Brothers, all of them looking like spaniels, and, to my ears, a total load of MOR crap. Still, it’s not aimed at me.

After reading Allison Pearson’s excellent new novel about the David Cassidy cult of the mid-Seventies, and observing the overheated expressions on the faces of the Jonas Cult, one wonders whether there will ever be anything new in the world. Out of Africa always something new, the ancients observed: and out of America always something you’ve seen before, they might have added. There will always be a puppy-faced American boy of impossible cleanliness singing rubbishy ballads about love; there will always be 13-yearold English girls behind a barrier, shrieking out of the sheer pleasure of spending an afternoon like this with your mates.

They’ll laugh about it in the future. For the moment, I’m sure they wonder sometimes: if they were ever in a position to be in the same room as one Jonas Brother, or all of them, what would they actually do? Whisper “Hello” and then faint, I expect. I wish I could feel that excited about anyone, really.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments