Peter Popham: Aung San Suu Kyi meant to leave Britain for a few weeks – not 24 years

She and her family paid a terrible price about which she has never been willing to speak

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The look on her face as she arrived at the airport yesterday, a blinding smile on the point of bursting through her pursed lips, said it all: this was a homecoming. The word may not be diplomatic – for years she fought against the canard spread by Burma's junta that she was not really Burmese but a tool of foreigners, a creature of the hated British oppressor – but it contains plenty of truth.

When she left the family home in Park Town, Oxford, on 31 March 1988 and flew to Rangoon to nurse her gravely ill mother, it was a mercy dash, no more. She was going away for a few weeks or months, not 24 years.

Oxford had been her home twice over: in 1964 she had arrived from Delhi, where her mother, Daw Khin Kyi, was the Burmese ambassador, as a fresher at the all-female St Hugh's College, to take a degree in politics, philosophy and economics.

She threw herself into student life, teaching herself to punt, buying a Moulton bicycle and volunteering as a stage manager on plays. She was appalled by the adventurous attitude of her fellow students to sex. "I will never sleep with anyone except my husband," she declared, to the derision of the others, "until then I will just go to bed hugging my pillow". She was not a brilliant student: twice she tried to change her course, without success, and emerged with a third-class degree, which hampered attempts to return to academic life.

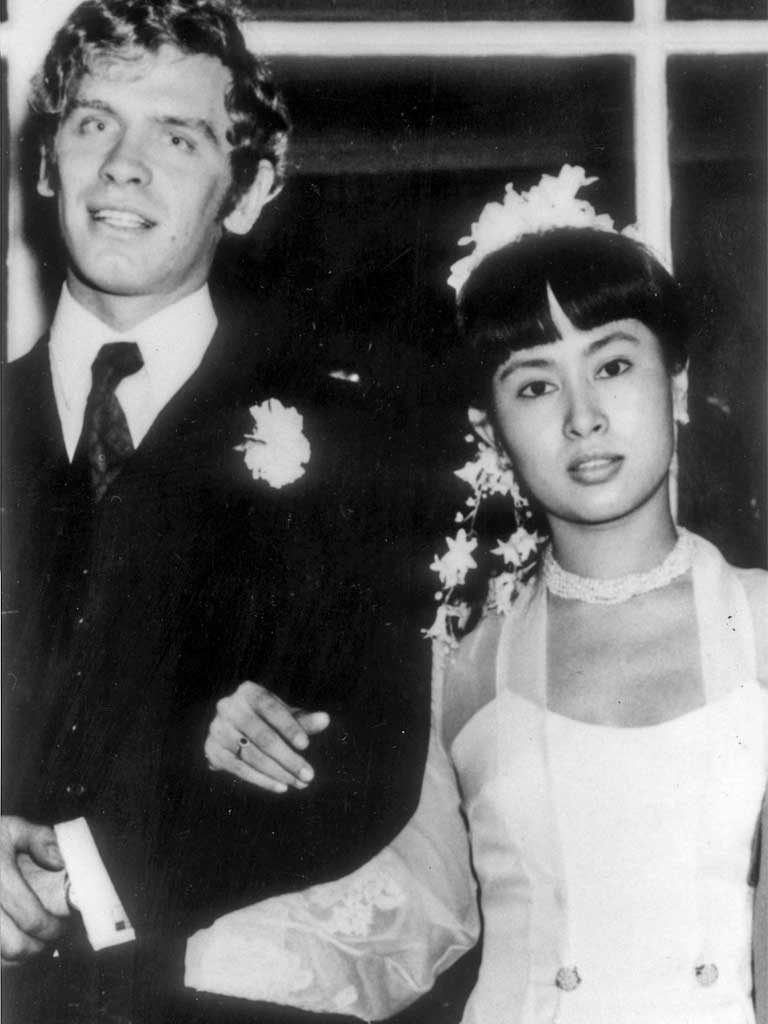

After marrying Tibet scholar Michael Aris in 1972, they settled in the city, eventually moving to a Victorian house with their sons Alexander and Kim. Once the children had got past their first years of school, she set about fulfilling her early ambition to be a writer: her best and most important work was a biography of her great father, Aung San.

Oxford was her life. Back in Burma, in 1988, students and others pressed her to join the democracy movement, but she resisted. She knew what it would mean: there would be no dipping a toe in then withdrawing it. Burmese politics had killed her father, assassinated before he could become the first prime minister of independent Burma. It was not for herself that the delegations wanted her – she had never made a political speech or taken a political stand – but because she was her father's daughter and would bring the lustre of his name to their movement.

Finally, she agreed. She and Michael were aware it would massively disrupt their domestic routine, but neither could have anticipated that it would blow the family apart. Michael wrote in a cheerful letter home after she had taken the plunge – the whole family was there to watch her make her first major speech, before a million people outside Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon – that he hoped the tottering junta would collapse by Christmas, then family life could resume.

Whether Suu was ever quite that sanguine is not clear. But in their worst nightmares they could not have foreseen the terrible years ahead: the way the regime would deliberately prevent her husband and children from visiting her, cynically exploiting her emotions to try to drive her out of Burma for ever.

Of course she never succumbed, and all four of them paid a price about which she has never been willing to speak. Oxford, where she travelled yesterday, remained intensely nostalgic. Buddhism warns sternly against attachment, and that includes attachment to place. But to the extent that this devout Buddhist can admit the concept, England for Aung San Suu Kyi is home, quite as much as the villa in Rangoon where she spent so many years confined.

What she must be feeling today, after a birthday reunion with her English in-laws, other relatives and friends in the city where she lived for more than 15 years, is impossible to imagine.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments