Patrick Cockburn: The strange forgettability of some civilian massacres

World View: It is too soon to know if the deaths of an Afghan family last week will alter things in Afghanistan, but some atrocities have the power to shape history

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

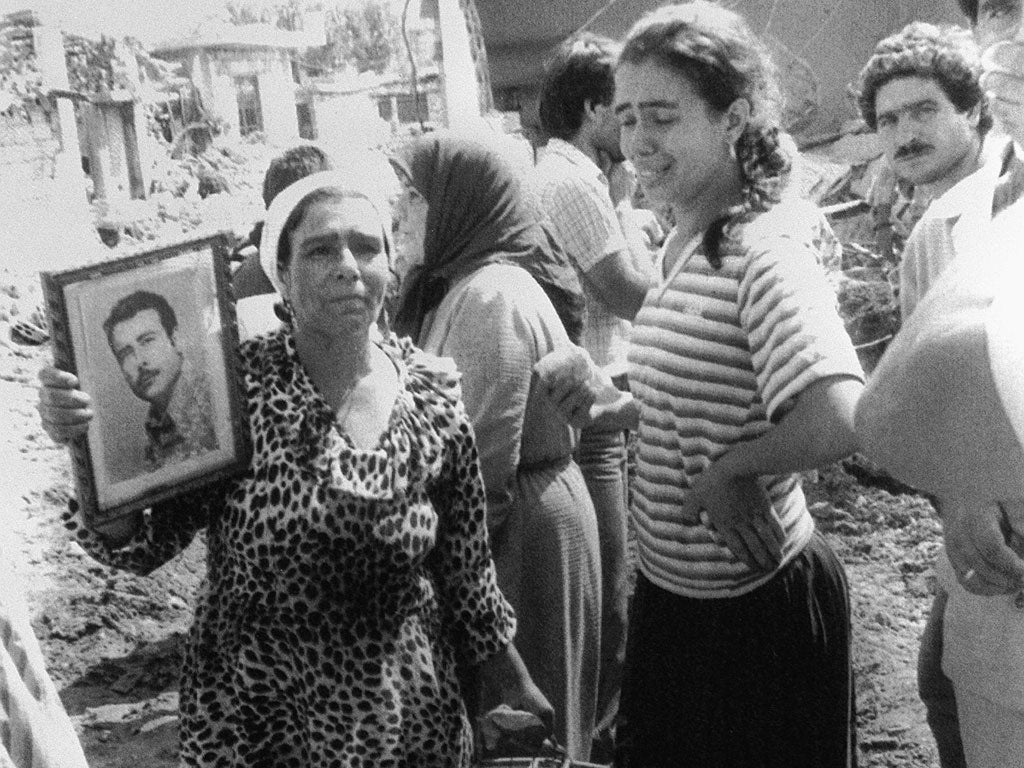

Your support makes all the difference.I remember walking into Sabra and Shatila in south Beirut in 1982 just after the massacre of at least 1,700 Palestinians by Christian militiamen loosed on the refugee camps by the Israeli army. There was a sweet, sickly smell from the bodies of people that were beginning to bloat as they lay heaped up in small shops and alleyways. Most were old men, women and the young, some half buried by a bulldozer that had pushed sand over them. The effort at hiding the slaughter was half-hearted, leaving heads, arms, legs and rags of clothes of the dead sticking out of the ground.

It would be wrong to say the memory of the massacre never left me, because for years I did not think about it. I even lost the clipping in the Financial Times, for which I then worked, describing what I had seen. But then, in 2008, I saw a brilliant animated film called Waltz with Bashir, by the Israeli director Ari Folman, about how he had been at Sabra and Shatila but had suppressed any recollection of it. So had Israelis as a whole. Just before the end of the film the animation ends and turns into news film. It shows a group of Palestinian women wailing with grief as they search for their murdered families. It is a moving scene and, I believed, new to me until I suddenly saw that, walking with the group of women, was myself.

It would be nice to say that the exposure of the Sabra and Shatila massacre changed things for the better, but it did not. The Israelis once again killed Palestinians and Lebanese civilians on a mass scale in 1996, 2006 and 2008. Describing the slaughter of Lebanese at Qana in south Lebanon in 2006, Anthony Shadid, the New York Times journalist who died in Syria in February, wrote that "where Israeli bombers caught their victims in the midst of a morning's work, we saw the dead standing, sitting, looking around". A one-year-old baby had died with its pacifier dangling from his body, and a 12-year-old curled into a foetal position seemed to be vomiting earth.

Massacres vary in their impact. Small atrocities can become the building blocks of history and others, in which greater numbers died, are soon forgotten. Mass killings by the government against peaceful protesters resonate more than those that are a by-product of armed conflict. What starts as an attempt to intimidate opponents can irreversibly delegitimise a state. British rule in India was fatally undermined by the massacre of unarmed Indian protesters by British troops in Amritsar in 1919; and the shooting of 13 demonstrators by British paratroopers on "Bloody Sunday" meant that the many Roman Catholics previously hostile to the IRA would now tolerate it. In each case, the opponents of British rule were enormously strengthened both by what had happened and by anger at official lies.

Will the latest massacre in Afghanistan have long-term significance? The facts are well established. An American army sergeant shoots 16 Afghans, mostly women and children, in two villages in Kandahar province a week ago. The impact so far appears to have been greater outside than inside Afghanistan. Foreigners may be shocked by the killings of civilians, but Afghans will scarcely find it unprecedented. The 16 dead in Kandahar will appear to many as just more of the same, differing only in that the latest crime is more blatant and undeniable.

Compare this to a much bigger massacre in Farab province in eastern Afghanistan in 2009, when US bombers killed 147 people in three villages. I was in Herat, the city to the north of Farab, but it was too dangerous for me to drive to the devastated villages because the Taliban were strong in the area. There was evidence that all the dead were civilians. Enraged farmers drove their tractors with trailers filled with the corpses of their relatives to protest outside the governor's office in Farab city. The initial Nato story was that the Taliban might have killed the civilians themselves by throwing grenades into houses, but this did not explain the giant craters. Late in the day, there was a grudging official admission that the US aircraft might have destroyed the villages. But the story never took off internationally because it could not be verified.

Massacres are often only the culmination of a long line of violent incidents, which have previously been ignored by all except the victims. When photos of US prison wardens mistreating inmates were published in 2004, the impact was greater outside Iraq. Iraqis were indeed frightened by US troops, but less by Abu Ghraib and more by shootings at vehicles that got too close to US convoys.

All contested occupations have the potential for atrocities by occupying troops. There was a time, during national service and mass mobilisations, when this would have caused no surprise. Soldiers were considered by home populations as dangerous young men with semi-criminal tendencies.

The Duke of Wellington was denounced for snobbery for calling his men "the scum of the earth", which was true. He was accused of inhumanity for favouring retention of the lash, but he argued that without the threat of a beating there was no way he could safeguard civilians from his soldiers.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments