Olaf Cramme: Hollande will go via Brussels to rescue France

A victory for the Left in today's French election would help those who want more regulation on the City of London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

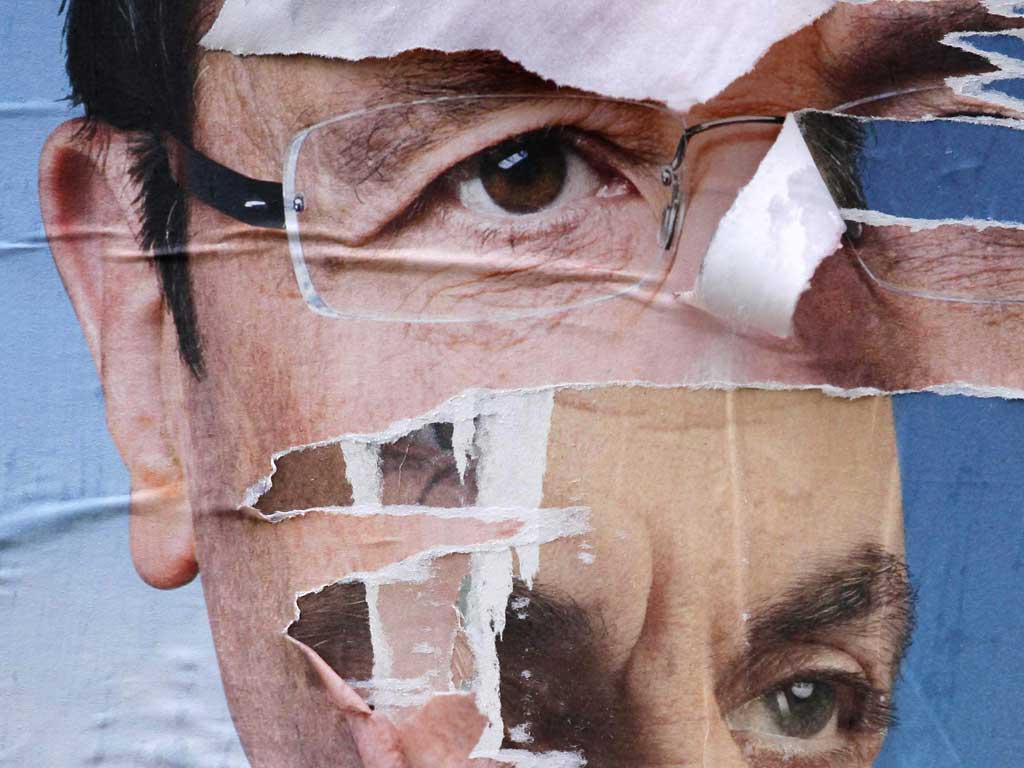

Your support makes all the difference.Today, people from across the globe are looking at France in the expectation that the dry and colourless François Hollande will take the presidency. The last time such a major political happening occurred was in 2008 when the world was gripped by the inescapable appeal of Barack Obama and his ideas for radical change. It tells you everything you need to know about the state we are in: then, the animating theme was hope. Now, it is fear.

Much of Europe has been returned to recession. The eurozone crisis is out of control again. Unemployment is rising almost everywhere, with one out of two youngsters on the streets in some countries. People across all segments of our societies are anxious about their status, living conditions, income or job prospects – often all at once.

Against this background, it almost seems that Europe is much keener on Hollande than France itself. In France, it was the unpopularity of Nicolas Sarkozy that dominated the electoral contest before the Front National stole the headlines. Hollande's tactic has been to portray himself as "Mr Normal". French voters seem to approve, yet show very little enthusiasm for his ideas on how to prepare the country for the future.

In Europe, however, the expectations are excessively high. Two camps of believers stand out: pro-Europeans, who are tired of defending the EU and the euro in the light of the present Franco-German (mis)management; and social democrats, who virtually lust for a political and ideological resurrection after years of marginalisation.

Hollande's central message appeals to both sets: the global financial markets are the new enemy. They must be determinedly reined in for the primacy of politics to return. Only then can we create a fairer society and reinforce solidarity within and between member-states.

For pro-euro Europeans, this is a welcome change of tune from the dogmatic emphasis on austerity, said to be policed by rapacious financial markets. According to an increasingly popular view, such pressure can only be broken by a resolute shift of focus on to growth, if necessary through a new coordinated stimulus, ideally matched with the creation of a European credit rating agency with a more benign view of the common currency.

For social democrats, it provides new certainty that the battle between capital and labour is far from over. At last, a new mission has been found, reminiscent of the good old days when the task was to build up an industry-led, "real" economy.

But how likely is it that Hollande will meet these expectations? There is no doubt that the eurozone needs a plan B. Today, the EU feels cold, polarised and leaderless. Hollande's arrival would bring a breath of fresh air, urgently needed to restore the "common purpose" pivotal to the eurozone's future. Hollande and Angela Merkel's conceptions of European integration are not really that far apart. She will be happy to perform yet another U-turn in the interest of EU consensus, which remains Germany's overriding concern.

Initial hiccups may be unavoidable, but Hollande is less of a "Gaullist" than Sarkozy and more inclined to strengthen the EU's centralising institutions. In the long run, this – and not the row over a few more growth-enhancing investments – could make the real difference in shifting the eurozone from a flawed, decentralised rules-based system to a proper fiscal and political union.

So pro-Europeans might have something to cheer. But things are less clear for the left. Apart from a few electoral gimmicks – like the questionable 75 per cent top tax rate for those earning €1m – there is no social democratic blueprint which is set to overcome the deep split between communitarians and cosmopolitans, or the tensions between social justice and economic efficiency. There is also no new macroeconomic model which can alter the rules of the game.

Instead, by committing to fiscal prudence and a balanced budget, Hollande bows to France's massive challenges: debt to GDP of about 90 per cent, a worsening trade deficit and an unsustainable public spending ratio. He might have campaigned on inequality and fairness, but from day one he will be engulfed in a battle about restoring competitiveness, job creation and fiscal retrenchment. Disappointment among his own supporters looks inevitable. European social democrats will think twice about what ideas they can actually borrow.

Yet, even if this sobering picture comes true, one important lesson remains for the centre-left: Hollande is only too aware of the narrow policy space which politicians now inhibat. He knows about the contest between the dynamics of the global economy and the struggle of national politicians to control and temper it. He deliberately abstained from following François Mitterrand's initial intentions to resurrect "socialism in one country". In lieu thereof, should he win today, he looks likely to pin his hope to the European Union, despite the habitual grand rhetoric of French exceptionalism. Imperfect though the EU might be, it still remains Europe's most promising device for creating the policy space in which real political choices can be enacted.

What does this mean for Britain? The Government is likely to face even more of a headwind in its attempt to liberalise the EU from the outside. If anything, Hollande will take an even harsher line on regulatory issues, with the City of London as the main prize. For Labour, it means accepting that the centre of gravity in European social democracy has definitely shifted from London to Paris. But this should offer a new chance: without experimentation and new governing ideas, the left cannot regain its past dynamism and élan. Hollande will have to try this out on the back of the EU. Labour should watch closely and engage.

Olaf Cramme is the director of Policy Network and a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics' European Institute

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments