The President's extraordinary Joe

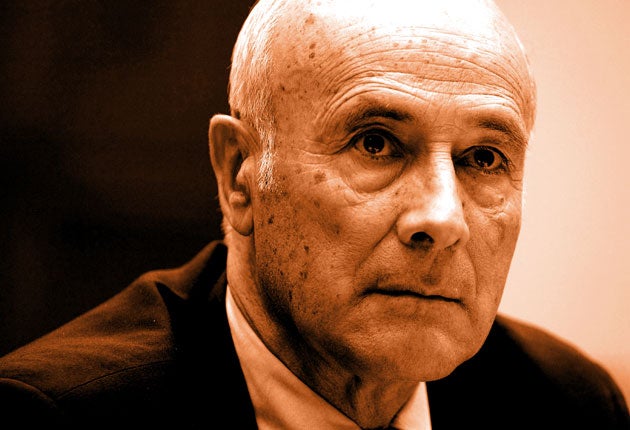

He's the US professor who moves between academia and politics with ease, and whose term 'soft power' defines diplomacy in the Obama era. Mary Dejevsky wonders why Britain doesn't have its own Joe Nye

There are book tours and book tours.

And the one that has taken Harvard professor, Joseph Nye, around the UK over the past two weeks was at the very high-class, high-minded, end of the spectrum. At 74, the authority on international relations – and much, much else – could be said to be at the height of his influence.

Nor is there the slightest hint that he might be slowing down. His programme was as packed with engagements as that of any rock star with an autobiography to sell. His Harvard assistant of many years told me, when I rang her to clarify exactly what his timetable had been, that she had known nothing like it. She was exhausted trying to track it. If there is such a thing as an Ivy League circuit in the UK, Nye played it. He spoke at breakfasts, lunches, teas and dinners, giving a host of interviews in between. In London he ran the gamut of the think-tanks, with formal lectures at Chatham House – the Royal Institute of International Affairs – the RSA (Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce), and the LSE. He was the lead speaker in a symposium at Oxford called "Major Powers and International Responsibilities"; he spoke at the Bristol Festival of Ideas. His final engagement, last Thursday, was in Cambridge to deliver the inaugural lecture at one of the University's newest ventures, the Centre for Rising Powers. His subject on this occasion was the future of US-China relations. In between, he conversed with MPs, met Foreign Office diplomats and gave a plethora of broadcast interviews. I caught him on Night Waves on BBC Radio 3 and then on BBC Television's Newsnight, in a strangely prickly encounter in which his characteristically mild and unruffled manner seemed to ruffle Jeremy Paxman mightily. It was hard to pin down exactly why the Paxman-Nye encounter did not work.

Maybe Paxman understood that you just don't do adversarial with American academic luminaries – friendly obeisance is more like it – but did not know which other register to choose. Or maybe it was just that they were both tired at the end of a long and unusually warm day.

All this frenetic activity was in aid of Prof Nye's new book, The Future of Power. If you were feeling uncharitable – not a notion, it has to be said, that his precise and affable manner in any way incites – you might describe this as the latest spin-off from the work that, more than any other, elevated him from leading US academic to the status of fully-fledged global guru. This was the book he published in 2004, called Soft Power: the Means to Success in World Politics. That work itself, though, was the development of a book he had penned almost 14 years before: Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. Published in 1990, this is where the term "soft power" originated. Nye distilled the concept in an article the same year for Foreign Policy magazine, whence it gradually penetrated the conference and policy circuit to become not only THE turn of the century buzz phrase in international affairs, but recognised as a way of exercising power in practice.

Its continuing magnetism can perhaps be gauged by the fact that, as a term, it has now drawn into its embrace even Russia – widely seen as a traditional "hard-power" state if ever there was one. In Moscow last autumn, I was in an international group that met the Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov. Russian-US relations were thawing, following President Obama's decision to "push the re-set button", and Russia's President, Dmitry Medvedev, had responded with peace-generating murmurings of his own. Listening to Lavrov, I suddenly heard what I assumed was the Russian for "soft power", almost jumped out of my skin and remarked on it afterwards – only to discover that the translator had not rendered the two crucial words into English as "soft power", demonstrating just how much of a novelty this addition to Russia's diplomatic lexicon still was.

The phenomenon of "soft power", of course, had been around for centuries before Nye coined the phrase. It is probably as old as diplomacy itself. You can also, if you like, single out Machiavelli as an arch-exponent of its manipulative strain. Shorn of such ulterior motives, however, soft power is exercised by states or leaders who get their way not by force of arms, but through influence, authority and the attractiveness of example.

Nye's genius – and good fortune – was to encapsulate quite a complex constellation of ideas in a single phrase, at a time when there was a hole in the academic and political landscape just waiting for it. The democratic revolutions in east and central Europe, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War that came with it, together bounced two new expressions first on to the international conference circuit and, very quickly, into wider usage. Francis Fukuyama's catchy "end of history" was one; Joseph Nye's "soft power" was the other. Arguably, Nye's coining shows fewer signs of wear two decades on. This is partly because it appealed to Bill Clinton when he was – unexpectedly – elected President in 1992. As a bit of a foreign policy-wonk himself, he had an intellectual affinity with Nye. They had both been Rhodes scholars at Oxford – though several years apart; they had both travelled more than many of their Americans contemporaries and they both had a natural sensitivity to other cultures.

Once in the White House, however, Clinton was perpetually thwarted in putting "soft power" into practice.

His authority was undermined by the loss of Congress in the mid-term elections two years later. Then the US lost troops to violence in Somalia, then in Lebanon (the bombing of Khobar Towers), then Yugoslavia descended into mayhem. All the while the calls were for the exercise of more hard power, not less. Clinton found himself chided for his timidity. When he did authorise retaliatory air raids on Afghanistan after the presumed al-Qa'ida bombings in Kenya and Tanzania of 1998, he was accused of using the country's armed forces to distract from his personal discomfiture (the Monica Lewinsky affair) at home.

The heyday of "soft power" as a concept probably coincided with George W Bush's post-9/11 rush to arms. It supplied the antidote to the rhetorical question asked ever more loudly by Republicans during the Clinton years – and now taken up double forte by the Tea Party movement: what are the US armed forces for, if not to be used?

Joe Nye was an enthusiastic recruit to John Kerry's doomed campaign for the presidency in 2004 – Kerry being perceived as another "Europeanised" American on foreign policy – but, with the US still in the shadow of 9/11 – "soft power" turned out to be short of electoral attraction.

Paradoxically, George W Bush's presidency, which left the United States at war on two fronts, may have been the best thing that happened to "soft power". As the war in Iraq became discredited among ordinary American voters, "soft power" supplied a ready-made alternative. And when Barack Obama – like Bill Clinton, an internationalist in outlook – was elected President, in part because of his opposition to the Iraq war, the concept of "soft power" acquired a new lease of life. Not only was it was contrasted with the "hard power"– a state getting its way by force of arms – that was identified with George Bush.

It was also refined. Prof Nye came up with a new term, "smart power" – knowing how to combine the two to maximum advantage – which was taken up with alacrity by Obama and his Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton.

That the notion of "soft power" started to feature in US foreign policy for real, however, and not just in theory and on the conference circuit, reflected one of the ways in which government in the United States differs most sharply from that in Britain. Whereas academics in the UK tend to pride themselves on having an arm's length relationship to power, or at least regard this as the normal state of affairs, academics in the United States expect to become practitioners, moving in and out of government. And they are drawn in not just in an advisory capacity, but to full executive appointments as secretaries and under-secretaries of state.

This has its disadvantages: the scale of movement in and out of government when a new US administration takes over can render its first year distinctly problematic, as the new recruits are sounded out, go through security clearance and learn the ropes.

The administrations of both Clinton and Obama were probably less effective in their early months than a new British government would be, made up of ministers who have served in a shadow cabinet and backed by a permanent Civil Service, whose top ranks are not political appointees.

The advantages of the revolving door between academia and government, as it works in the United States, however, are indisputable. It gives academics an opportunity to test their ideas in practice and it gives politicians the benefit of specialist advice. Mid-career, Joseph Nye spent two years as a security official specialising in nuclear non-proliferation in the administration of Jimmy Carter. Fifteen years later, he joined the Clinton administration as assistant secretary for defence, and then became chairman of the National Intelligence Council, a body that coordinates intelligence estimates for the President. Had John Kerry won the 2004 election, Nye was seen as the natural choice to be National Security Adviser. When the Republicans were in power, Nye returned to Harvard.

Such a career would be unusual, not to say impossible, in Britain. Despite hints by Tony Blair, among others, that he would favour academics, business people and others moving in and out of government, the structures are not there and no-one – not the professional politicians, not the civil servants – has a real interest in fostering change. When it does happen, it is the exception and the beneficiaries – Admiral Lord West, for example – have tended to be more accident-prone than other ministers. Sharing a platform with Nye during his sojourn in London, Mark Malloch-Brown – former Deputy General Secretary of the UN and Foreign Office minister under Labour – lamented Britain's single track with more than a touch of envy. At very least, serving in government can be said to lend a practical aspect to the various branches of political science at America's leading universities.

Nye's direct experience of academia and politics – two worlds which in Britain tend to be seen as alien to each other, if not inimical – is the rule rather than the exception for senior US scholars and it ensures that their ideas are given a hearing on both sides of the fence. It allows the two worlds to feed off each other to mutual benefit and those who excel in both become a particular kind of superstar, guaranteed a global audience and needing to feel beholden to no-one.

Nye came to London with two arguments proceeding from his latest book, both of which deserve a hearing, not least because they go against the grain of the current international consensus. The first is that the United States is neither in terminal decline nor doomed to such a fate. The second – not unrelated – is that China will not take over as the world's leading superpower very soon, if ever.

With the United States, Nye draws a distinction between absolute and comparative decline and insists that, while the US may be in comparative decline against, say, China, it is not in absolute decline.

He even challenges the view that the US is in comparative decline, pointing out that US demographics are healthier than China's, where the one-child policy has produced an ageing population.

This is one reason why China's economic growth is likely to slow. He warns against concentrating on China's national GDP, while ignoring its comparatively low per capita GDP and argues forcefully that the limits Beijing places on political and creative freedom are likely to constrain the country's overall development. In his relatively downbeat assessment of China's medium-term prospects, Nye is not alone.

His misgivings are shared by another of America's global gurus, Nouriel Roubini. The professor of economics at New York University surprised China-enthusiasts recently by warning that China's economy would not be able to sustain its present growth and could suffer a hard landing after 2013. Roubini, it may be recalled, is distinguished as one of the very few US economists to have forecast the 2008 financial crash.

For anyone whose appetite has been whetted, I have it on good authority that the professor of "soft power" will be back in the UK before the month is out. And while the British generally take a wary attitude to international gurus, it is worth bearing in mind that what Nye and Roubini think today has a habit of becoming the global consensus tomorrow.

Those political buzz words – and who coined them

By Mike Bonnet

'Compassionate Conservatism'

'In the United Kingdom at least, the people responsible for introducing the term "compassionate conservatism" into the political lexicon of the day are Conservative MP for Hereford and South Herefordshire, Jesse Norman, and Janan Ganesh, a researcher at conservative think-tank Policy Exchange. Their 2006 book Compassionate Conservatism: What it is – Why we need it defined the concept as "a view about what we, the people, can do for ourselves". Under David Cameron, the Conservatives have used the phrase to explain their adoption of policies not traditionally thought of as Conservative, such as those relating to social justice and environmentalism.

'The Tipping Point'

In his 2000 book of the same name, Canadian journalist and author Malcolm Gladwell popularised this expression, which has come to mean an irreversible event that makes a certain outcome all but inevitable or, as Gladwell describes it: "That magic moment when an idea, trend, or social behaviour crosses a threshold, tips and spreads like wildfire." Though used traditionally in the sciences to denote a change in the equilibrium of objects, Gladwell is thought to be the first person to apply this concept to sociology. Most recently, the phrase has come to be used to denote the point in climate change, as yet not reached, when the melting of the polar ice-caps becomes a certainty.

'Shock and Awe'

When two former servicemen-turned-political advisers, Harlan Ullman and James Wade Jr, wrote their 1996 work Shock and Awe: Achieving Rapid Dominance, they can scarcely have realised the impact it would later have. Fast-forward seven years to the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the descriptions from the United States military of aerial assaults on Baghdad made the expression known the world over. Indeed, in the aftermath of the attacks, Sony sought to register "shock and awe" as a trademark in advance of a planned (later scrapped) videogame release.

'The Big Society'

Criticised by both Labour and the Liberal Democrats for being vacuous, The Big Society was the flagship policy in the Conservative party's 2010 election manifesto. The brainchild of Phillip Blond, director of Conservative think-tank ResPublica and the subject of a book by Conservative MP Jesse Norman, the Big Society is described by the Cabinet Office as a policy that will "put more power in people's hands" and facilitate "a massive transfer of power from Whitehall to local communities." It is, without doubt, the big entrant into British political vocabulary of late.

'The Third Way'

Representing a supposed compromise between left and right wing politics, the third way is a long-established political trope made famous in the UK by Tony Blair's Labour party in the 1990s. Given its association with New Labour, the idea would appear to have its origins in an unlikely source – former Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, who wrote a 1938 work of political theory, entitled The Middle Way. Under Tony Blair, however, the third way became a key component of Labour modernisation and break from its militant past as the party ended 18 years of opposition with its 1997 election win.

'Mission Creep'

This Americanism has come to be used as a condensed definition for a project which extends further than its originally stated goals. Predominantly used to describe military operations, particularly those in which Western powers exceed the terms of agreed UN resolutions, examples of so-called "mission creeps" include Iraq, Afghanistan and, most recently, Libya.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments