Margaret Drabble: Defer to them or mock them, either way the royals have us in their grip

Even those who claim not to be interested, are as full of anecdotes as the most hardened royalists

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

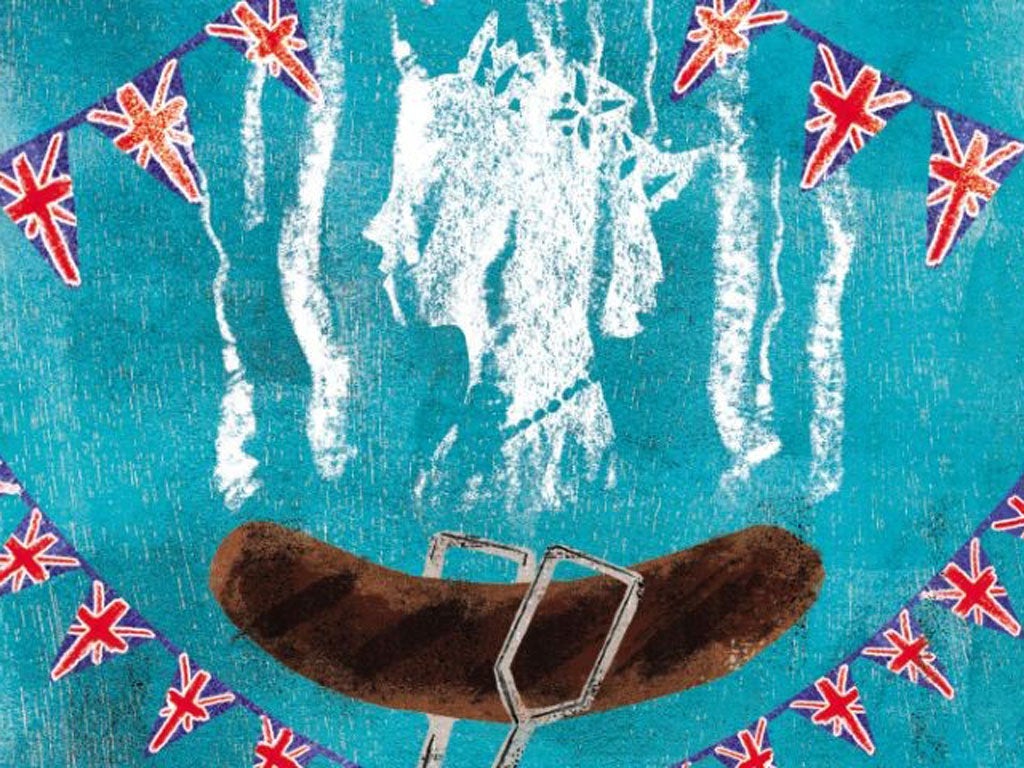

Your support makes all the difference.What a simple world we lived in 60 years ago! My generation remembers so well the tinned salmon sandwiches, the sherry trifle, and going down the street to watch the coronation with the only neighbours who had TV. It's become a universal folk memory by now. A friend recalls that his school in 1952 gave him a Bible and an orange ice lolly to mark the Queen's accession: a wonderfully bizarre conjunction. Our Queen is our social history, and we have measured our lives along with hers. We have dreamed about her – she is always so friendly and so natural in dreams – and when I was a schoolgirl and she was still a princess, a group of us wrote her a letter commiserating with her lonely and protocol-bound life, unable to hop on a bus or enjoy a shopping spree. We got such a nice letter back from an underling. We knew all about her, of course, from indiscreet governess Crawfie, and a lot of us were called Elizabeth or Margaret, although our parents would never have acknowledged the influence, and we weren't supposed to read Crawfie. It's subliminal, the influence. It lurks in the fabric.

Were we being sycophantic or cynical when we wrote to Lilibet? It's hard to tell the difference. Deference and mockery, as far as the royals go, walk hand in hand. They have us either way. We may pretend not to be fascinated by them, but don't believe those who claim they are not interested, for they are as full of anecdotes as the most hardened royalists. Sue Townsend, our most outspoken abolitionist, seems to know the whole family very well, and her riotously satirical novel of lese-majesty, The Queen and I, displays a wicked familiarity with all the characters of the Windsor soap opera. The satire and the comedy depend on our recognition of the stereotypes – a conscientious queen, queuing meekly for her benefits while remembering Crawfie's exhortations to retain self control; sulky Philip, mad in an NHS bed; Princess Anne, handy with the plumbing; and Charles, happy with his tomatoes in their growbag.

The Queen's personal popularity, in her Diamond Jubilee year, is higher than ever. This is a tribute to her survival. We congratulate ourselves for still being alive as we watch her smile and smile again. A few years ago, the Canadian press dared to make rude comments about her unsightly varicose veins when she graciously visited their land, and I found that very offensive. What did they expect, at her age, and with all that standing about? When I was presented to the Queen Mother, I noted that she had a large piece of sticking plaster on her leg. Again, this aroused in me not mockery but sympathy.

We honour the Queen for her capacity to endure boredom gracefully. It is true that she receives incorrect and ill-advised guests from time to time – murderous despots, polygamous heads of state – but think of the excruciating tedium of sitting through all those speeches and banquets. Like Victoria, she knows her duty. It cannot be possible that she enjoys these occasions. Does she, I wonder, manage to enjoy the food, of which the extravagant and patriotically sourced details are often released to her loyal subjects? Can the delight of agneau de la nouvelle saison de Windsor au basilic outweigh the tedium of the small talk?

Maybe the Diamond Jubilee will bring her some moments of fun, something more pleasurable than the relief of getting through public events without disaster. And the celebration of her 60 years will surely bring fun to others. Orange ice lollipops will be outdone by sausages, burgers, barbies, beer and champagne, and the upmarket parties will be vying to provide yet more exotic titbits. The Royal Academy celebration on 23 May (which I missed, alas, through a lingering virus) provided, according to my spies, little oriental delicacies on leaves and shells, an oyster bar, and "something purple on a bed of kale". No coronation chicken ice cream, though I gather that is now on offer in smart Soho.

We have come a long way, from the horror of thin Brown Windsor soup to frothy cappuccino of asparagus, from sardine sandwiches to lapsang souchong tea-smoked salmon, from austerity to binge and obesity. Maybe our insatiable appetite for curry was sparked by that startlingly successful coronation chicken recipe of 1953. We have become a nation of greedy, foodie, competition-obsessed voyeurs, a nation of virtual gourmets and actual gluttons, watching ill-tempered chefs showing off and insulting one another on TV and miserable amateurs attempting more and more ludicrous dishes in the eye of the camera and the heat of the kitchen. We love our humiliation. We watch eagerly, then we guiltily slope off to the supermarket to stock up with bangers and burgers and ready meals, or we reach for a mobile and dial for a pizza.

There were no pizzas or mobiles 60 years ago. I remember the first pizza I ate, in 1957, in Naples. It was crisp, thin, delicious. It was the food of the poor, but beautifully cooked. Now it is the food of the poor, baked in batches, and it tastes of hard raw burnt dough. In 1957, a home telephone felt like a privilege, a special instrument, hard to acquire, a status symbol. You had to queue for a new phone line in those days. You got one quicker if you claimed to be a doctor. We were, and remain, a class-ridden country. Is this the fault of the monarchy and the habit of deference? Melvyn Bragg thinks we've emerged into a class-free society, but I see no signs of that.

We may be in a double-dip recession, but the Diamond Jubilee marks an age of plenty, compared with the lean years of rationing after the war. We are still reacting to the war. When the Queen dies, the living memory of it will begin to pass away. She is our link. We know she was there and we can see it in her face.

My son Joe Swift met her at the Chelsea Flower Show. Her family spent nearly half an hour milling around his prize-winning show garden, as in a Sue Townsend scenario. She didn't venture in herself – she was nervous of the water feature – but she said she liked it, and that she liked watching Joe and Alan Titchmarsh on TV. My proud heart became royalist as I rejoiced to hear this. Joe thought it was all "a bit weird", but he was pleased to have his own royal anecdote now, he said, like everyone else. The magic still works, and Chelsea's flowers remain more innocent in spirit than masterchefs.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments