Kenneth O Morgan: A uniquely lovable figure in public life, he symbolises a lost world

He was the supreme icon of the British left, the last heir of the Edwardian Liberal man of letters – and politics may not see his like again, writes his biographer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a long, colourful life, Michael Foot played many parts. He was the supreme icon of the British left, a unique custodian and communicator of the socialist idea. He was a remarkable publicist, perhaps the greatest pamphleteer since the days of John Wilkes. He was a wonderful parliamentarian, the most compelling speaker of his day, cherishing the House of Commons in tribute to his family's nonconformist, west-country, Cromwellian traditions.

He was a central figure in post-war Old Labour's last phase, and was largely responsible for keeping the second Wilson and Callaghan governments in office. Less happily, he also became Labour's leader from 1980 to 1983, a veteran who inspired deep affection but also led his party to its heaviest defeat. Beyond this, he was perhaps the last heir of the Edwardian Liberal man of letters, another John Morley or Augustine Birrell, and politically more important than either. Over six decades, as an inspirational and civilising force, he symbolised a world we have lost.

He first made his name at the age of 27 after the publication of Guilty Men – written just after Dunkirk and published under the pseudonym Cato – of which Mr Foot was the main author. Written with irony and passion, it combined the rhetoric of the Methodist chapels and the Oxford Union with the journalistic flair of a dashing young editor. In six months, it sold over 200,000 copies. Its impact on the public anticipated Churchill's histories in setting in stone a received view of the disastrous folly of Chamberlain and the appeasers. Mr Foot went on, with pamphlets and tracts by the score, to show himself to be the greatest polemicist of his time – socialist, populist, fundamentally patriotic like his comrade George Orwell.

He sat in Parliament for 42 years, the first 10 for Devonport in his native Plymouth from 1945, the last 32 as the heir to Nye Bevan in Ebbw Vale. Here, until 1970, Mr Foot was a relentless rebel. Bevan was his touchstone far more than Lloyd George or Cripps had been in the past. Mr Foot used his editorship and long connection with Tribune to make it the mordant voice of the traditional left, calling for more socialism at home, a more non-aligned foreign policy and nuclear disarmament.

He was a leader of Keep Left in the 1940s and the most vehement of the Bevanites in the 1950s: he never forgave Hugh Gaitskell for, as he saw it, driving his hero, Nye, out of office and undermining his socialist achievement. He was far more of a Bevanite than Bevan himself. CND marginalised him even more politically, not least because, unlike some of the leading unilateralists, he wanted the Labour Party to be converted, not undermined. Only in Harold Wilson's premiership did Mr Foot at last move towards the mainstream and seek power and responsibility.

To some surprise, he proved to be a highly effective minister, first as Secretary of Employment fulfilling the partnership with the unions, then Lord President of the Council, keeping a minority Callaghan government in office and striving might and main to push through Scottish and Welsh devolution. Jim Callaghan and Denis Healey were fulsome in praising the tireless loyalty of the deputy leader with whom they had so often been at odds in the past.

Mr Foot became the supreme champion of the trade unions. In 1974-76 he passed no fewer than six major bills, redressing the balance between employers and unions over employment rights, union membership or collective bargaining. Some of his legacy survives, notably Health and Safety legislation, and ACAS. Much of the rest was overthrown by the Thatcher government, and New Labour has done little to rescue it.

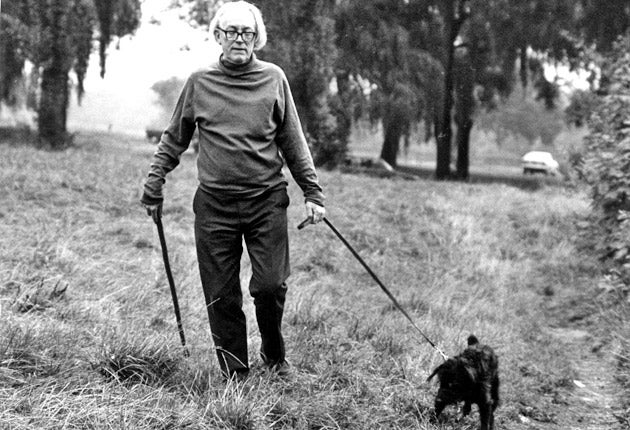

Quite unexpectedly, Mr Foot became party leader in November 1980. He was never cut out for such a post, and the press pilloried him mercilessly. He was depicted as "the old bibliophile" or, more savagely, Worzel Gummidge, waving his stick at his dog on Hampstead Heath or wearing an inappropriate coat at the Cenotaph ceremony. (One of the few who liked it was the Queen Mother, but the donkey jacket proved a more damaging garment than the mantle of Nye). Labour was almost ungovernable at this time, with the parliamentary party under fire from Trotskyites in the constituencies, and membership shrinking at the grass roots. There were serious defections to the Social Democrats.

Mr Foot led Labour to its worst ever defeat in 1983. Still, he was rightly seen as a unifying force at the time. No witch-hunter, Mr Foot created a base of personal loyalty and even began the purge of Militant. His "My Kind of Socialism" reinforced the Labour faith among such young protégés as Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and Robin Cook. Neil Kinnock built on this to try to make Labour electable again. Ironically, a major cause of his troubles lay in the Falklands War when the old "inveterate peacemonger" made his last great speech in the Commons, speaking as the patriot he had shown himself back in Guilty Men days.

Beyond partisan activities, Mr Foot created an image of the politician as a cultured, civilised, literate human being. His fascination with books, inherited from father Isaac, was no mere "hinterland", a spare-time hobby until he returned to his day job, but central to his views and his values, as was his love of history. Dean (Jonathan) Swift in particular was an inspiration, an erratic outsider who served the cause of peace in driving out the great Duke of Marlborough, another warlike Churchill, and whose Gulliver's Travels was one of the great imaginative chronicles, spiky and subversive. Mr Foot saw Swift as part of a great celestial literary genealogy ranging from Montaigne in 16th-century Bordeaux, through William Hazlitt in the French revolutionary era, down to H G Wells in suburban Edwardian London.

Mr Foot gave them all the same uncritical devotion he extended not only to Bevan and the Nehru dynasty but, improbably, to Lord Beaverbrook, his patron and second father. Mr Foot was never tribal in his affections. Just as in politics his friendships embraced even Enoch Powell, so in literature his heroes numbered Tories such as Disraeli. Mr Foot, the admirer of the Jacobins, was equally devoted to Edmund Burke, opponent of his admired Tom Paine and devastating critic of the revolution of 1789. Certainly Mr Foot was totally at home in the world of letters, with Orwell, Arthur Koestler and especially Ignazio Silone as his great enthusiasms – all three anti-Communist critics of the "God that failed". As for the other arts, there was always Michael's beloved Jill to educate him. As a partnership, they belong with the Webbs and the Coles in the socialist pantheon.

Michael Foot was a restless, complicated man. He kept the socialist idea alive, but contributed little to its philosophy. His definition of socialism was stuck in 1945's New Jerusalem – public ownership, planning, full employment and a welfare state. His biography of Bevan was his major contribution to the socialist faith. He was both populist and a patrician, a Friend of the People like Hazlitt in the 1790s. He saw himself in the great line of descent of English radicalism, from the Levellers to the Independent Labour Party. It was a patchy and partisan, but very usable, past. At least Mr Foot's attitude of respect stands in sharp contrast to the unconcern for history demonstrated amongst some apparatchiks within New Labour.

He was an internationalist by instinct, but also patriotically British, enthusiastic for Plymouth, Drake's Drum and the glories of the Royal Navy. His opposition to Europe (reversed in his last years) rested on his view of Parliament as the pivot of our island story. The peacemonger brandished the sword of retribution in Dunkirk and Dubrovnik. He grew up amid a background of puritanism, but he developed into a colourful romantic, devotee of women, admirer of the sensuous charms of Venice, and its most evocative poet, Lord Byron, happy in the mitteleuropa ambience of the "Gay Hussar".

He was a complex, contradictory man. He may not have changed ideas but he certainly changed lives. His style reflected his cherished quality, embodied in Hazlitt and Bevan, and given timeless voice by Danton in 1793 – audacity. He was a unique, lovable figure in our public life. Democratic politics may never see his like again.

Kenneth O Morgan has written the authorised life of Michael Foot

Michael Foot: The anecdotes that will outlive him

* In 1937, at the age of 24, Foot joined the staff of the London Evening Standard on the recommendation of Aneurin Bevan, having resigned from Tribune over the sacking of its editor. Bevan is supposed to have told the paper's proprietor, Lord Beaverbrook, on the phone: "I've got a young bloody knight-errant here. They sacked his boss, so he resigned. Have a look at him." Four years later Beaverbrook appointed a 28-year-old Foot editor.

* Foot and wife Jill were both lucky to survive a terrible car accident in 1963 when a lorry drove into their car. Foot later said how when he came round after surgery in a Herefordshire hospital a Salvation Army band was playing "Beulah Land, Sweet Beulah Land", a hymn that he had often heard in his Methodist boyhood: "I thought for a few seconds, in my half-dreamy state, that the rendering was being given by a more celestial choir. Then the mist faded; someone arrived with a bed pan and I knew I was restored to the care of earthly angels."

* He was lambasted in the right-wing press for wearing a "donkey jacket" to the 1982 cenotaph service, comparing him to an "out of work navvy". The jacket was in fact a duffle coat bought from a reputable retailer on Jermyn Street, which he later said the Queen Mother had complimented him on. In a later interview when asked if his wife Jill, who died in 1999, ever tried to tidy him up, he said: "She was furious about that because she thought people were blaming her for sending me out looking like that. I wasn't interested in clothes at all. But, you know, she made sure I didn't look disreputable, I think. I hope."

* Foot's 1983 election manifesto called for unilateral nuclear disarmament, withdrawal from the EEC, the abolition of the House of Lords and the re-nationalisation of recently privatised industries such as British Telecom. And because it included every resolution passed at Labour conference, it ran to more than 700 pages. Labour lost by a landslide, Foot resigned the leadership and Gerald Kaufman, who was then the shadow Home Secretary, famously described the manifesto as "the longest suicide note in history".

* Foot was a lifelong and devoted supporter of Plymouth Argyle, and on his 90th birthday in 2003 the club registered him as a player for a season with the number 90 shirt number. He never played but vowed not to "conk out" before he'd seen the club play in the Premier League – an ambition he failed to achieve.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments