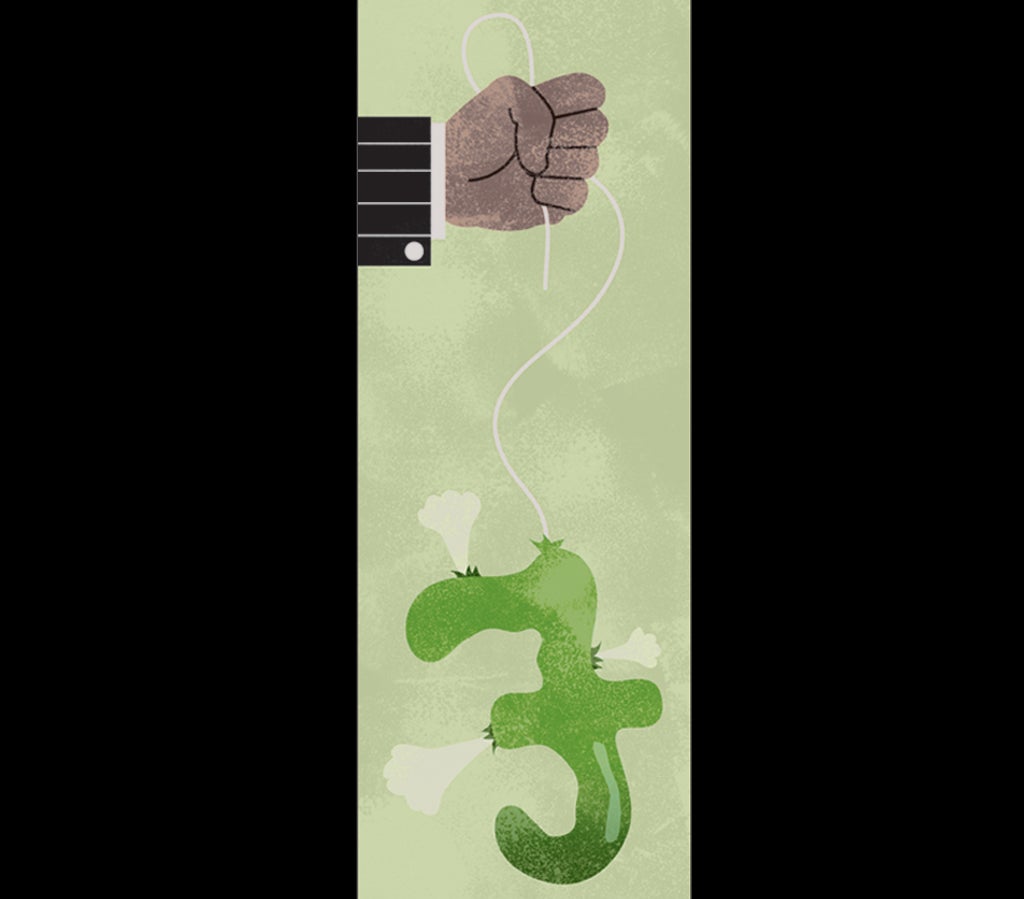

John Kampfner: A public mood that won't stand for corporate greed any longer

When it came to the bonus culture and tax loopholes, it took years for politicians to catch up with popular discontent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Is ethical capitalism an oxymoron? The answer to this question depends on your understanding of ethics. The term capitalism is clearer: a successful company maximises profits for its shareholders. How it achieves that is a combination of management priorities and procedures, state legislation and regulation, and public perception.

In some cases, notably banks, popularity is irrelevant. Returns on capital flows and risk are all that matters. If you are Adidas or Gap and modern consumers do not approve of your product or your morals (probably in that order of priority), you'll be meeting the receivers in no time.

The current political rhetoric around "responsible", "ethical" or "moral" capitalism should be taken with an enormous dose of salt. Where were all the leaders when the bankers were taking the money and running? They were united in slavish subservience, just as they appear united now in their condemnation.

It is salutary at moments like these, with David Cameron opining about the miscreant behaviour of Fred Goodwin and his like, to recall a speech given by Gordon Brown. It was delivered in April 2004, as he was trying to oust Tony Blair. "I would like to pay tribute to the contribution you and your company make to the prosperity of Britain," the then Chancellor declared. He was opening the European headquarters, in London's Canary Wharf, of Lehman Brothers, the bank that later went down the Swanee, almost taking with it the entire financial system. Talking of "greatness", Brown added: "During its 150-year history, Lehman Brothers has always been an innovator, financing new ideas and inventions before many others even began to realise their potential."

The present PM, in his speech yesterday, made some salient points. Labour did, as he claimed, make a Faustian pact with the City. It was based on a cowardly version of trickle-down – leave the wealthy to make as much money as they liked, in the hope that some of it would miraculously enter Treasury coffers to pay for poverty-alleviation, welfare and health spending. In Blair's case, it was prompted by admiration; in Brown's case, more by fear. But the result was the same – the acceleration of a process that had begun under the Thatcher government in which a tiny minority (the one per cent to coin the Occupy Wall Street term) lived in a hermitically sealed world.

Labour, Cameron said, "seemed frightened of challenging vested interests, believing the interests of big business were always the same as those of the economy as a whole". This statement is true, but also disingenuous. I cannot recall any significant Conservative intervention at the time calling for greater scrutiny of remuneration or for tighter rules.

Many small and medium-sized companies complain with justification of form-filling and other petty hurdles. But, when it came to the bonus culture or tax loopholes, it took years for politicians to catch up with simmering popular discontent. Unencumbered by accusations of being "anti-entrepreneurial", the Conservatives were quicker in seeing the financial crash of 2008 as an opportunity to change the rhetoric. George Osborne (who, I'm told, "gets it" a little more than Cameron), was first off the mark in trying to tackle the scandal of the "non-doms", the tax avoidance schemes that allowed non-domiciled citizens, who kept the number of nights in the UK below a required minimum, not to pay tax on their investments. Since then, there have been stories of the super-rich not paying their paltry Council Tax, and using a plethora of other wheezes.

Now with unemployment at a 17-year high, the recession has hardened the mood. The default position was to shrug one's shoulders during the time of relative plenty – when ordinary folk were being encouraged to spend even though their income barely rose.

How much of this will turn into action? Osborne's deal with the Swiss last summer to require back payments for previous tax avoidance and to require that country's secretive banks to hand over details of a few hundred accounts was seen by some as paltry, as the least on offer. But at least it marked a start.

Cameron pointed out that bonuses in bailed-out UK banks have been pared down; in a sop to the Daily Mail, he suggested that Goodwin's knighthood might be reassessed and that RBS might not give its chief executive, Stephen Hester, his planned bonus (I'd wager he's wrong on that). Most important, the Prime Minister confirmed that next week the Business Secretary, Vince Cable, will announce new measures on executive pay.

Cameron repeated the difference between the "deserving" and "undeserving" rich. In doing so, he and other politicians are raising a straw man. Few would surely deny the right of entrepreneurial whizz-kids to enjoy their newfound opulence. That battle was fought, and won, in the early 80s. There is no need constantly to invoke it.

In a pamphlet last month, the Conservative MP Jesse Norman described capitalism as "the greatest tool of economic development, wealth creation and social advance ever known". Whether or not this is true is irrelevant in this context. For the foreseeable future, capitalism remains the only serious economic method of exchange and production on offer. What matters, as Norman points out, is making it work.

In his most important passage, he harks back to the creation of the East India Company in 1599. It was "chartered directly by the sovereign for specific commercial purposes of conquest, colonisation or trade. Incorporation was a privilege that conferred economic benefits, and the purpose of the charter was to ensure that these benefits were in the sovereign's, and later in the public, interest".

Norman goes on: "That is to say, corporations exist not because of any divine or natural or common law right, but because we, the people, created them through legislation enacted in Parliament... over time, the privilege of incorporation has been transmuted into a legal freedom, and the link to the public interest has been all but forgotten." In other words, as corporate leaders exerted their power, politicians went soft. They became beguiled.

In order to succeed, capitalism requires rules, regulations and laws. People will always try to get away with it if allowed to. From the first traders and discoverers of the New World, to the globalised super-rich of the present day, the instincts remain the same.

John Kampfner is the author of 'Freedom For Sale'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments