Joan Smith: Assange cares for no one but himself

Neither whistleblower nor journalist, the hacker is a menace

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hacking has become one of the biggest stories of 2011, prompting so many arrests, police investigations and public inquiries that it's hard to keep track. The public has cheered on key players, including the actor Hugh Grant and the Labour MP Tom Watson, who have forced the scandal into the open. Strangely, there's another form of hacking, carried out using illegal methods and equally dubious in terms of morality, which millions of people actively support.

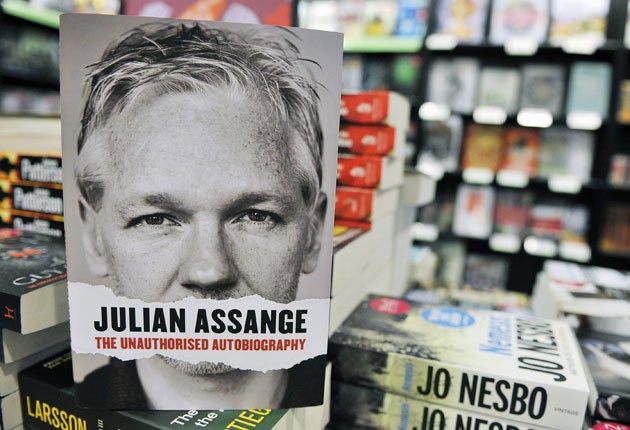

It has made an unlikely hero of the man who's become its public face, the Australian hacker Julian Assange, despite copious evidence of his paranoia, misogyny, political incoherence and all-round weirdness. Happily for those of us who have observed this ashen-faced celebrity-magnet with scepticism from the start, Assange has crowned a year of bad-tempered conflicts by falling out with himself and introducing to the language that novelty the "unauthorised autobiography". (I was thinking of writing my own autobiography but I've withdrawn co-operation from myself.)

There's a pleasing irony in the spectacle of someone who wanted to publish so much confidential information trying to suppress a book based on interviews he gave freely to a ghostwriter. But extracts published in The Independent reveal a man whose "struggle for justice through access to knowledge" co-exists with total insensitivity to other people and a profoundly irresponsible desire to make mischief. Early in his hacking career, Assange discovered how to get into the computers of vast corporations: "Turn off 20,000 phone lines in Buenos Aires? No problem."

Hugely amusing, no? Perhaps not if you lived in Buenos Aires, had a heart attack and couldn't call the emergency services. But I'm not convinced that consequences have ever been a major concern for Assange, who recently published 250,000 unredacted US diplomatic cables containing the names of confidential informants in Afghanistan and other countries. True to form, Assange blamed The Guardian, one of his media "partners" until they had a spectacular quarrel. But the limits of his commitment to human rights and democracy were exposed when he asked WikiLeaks' supporters to vote on Twitter for or against release of the cables. (Coming soon on Twitter, an important vote on whether I should have single or double espresso with my carrot cake.)

Assange's campaign for transparency has always sat oddly with his obsessive need for control. He isn't a whistleblower or a journalist, both of whom have to make fine judgements (unless they've succumbed to the hacking scourge) about what the public is entitled to know. It's entirely right that abuses by the US military in Iraq, say, should be exposed. But the notion that diplomats should never have a confidential conversation is risible. Democratic governments need inside information about the regimes they deal with; they need secret negotiations to protect human rights activists and their own citizens, using intermediaries who might be at risk if their involvement were known.

Assange's mission to publish everything from diplomatic gossip to unflattering verdicts on foreign governments is no more justifiable, in moral terms, than blanket tabloid intrusion into private life. His claim to be the "good" hacker has been undermined by poor judgement and the monumental ego that emerges when he mocks his opponents in his autobiography: "They needed a villain with silver hair, some kind of cat-stroking nutcase bent on serial seduction and world domination."

Actually, he's right. That's very unfair to Assange. I've never seen a shred of evidence that the super-hacker likes cats.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments