Jim Murphy: Our troops never rest. Why does the PM?

Having set a date for pulling British forces out of Afghanistan, ministers are being too passive - and are not even selling the policy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

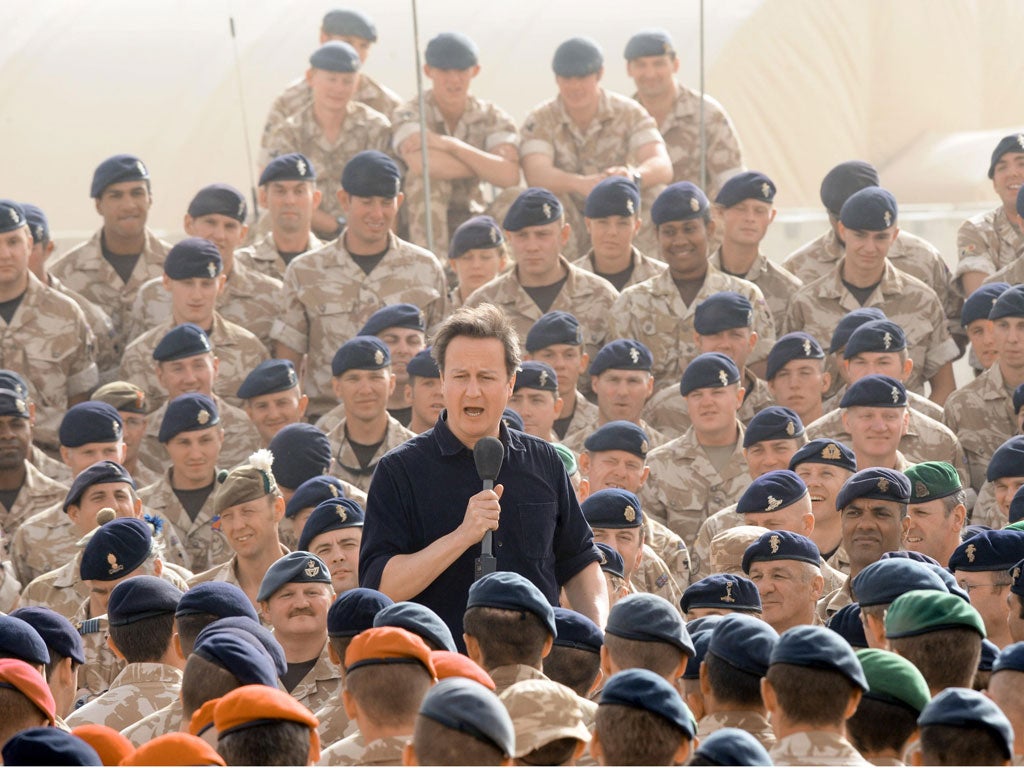

Your support makes all the difference.It is the responsibility of the government of the day to make the case for decisions over war and peace, yet David Cameron isn't doing enough in relation to Afghanistan. Significant events pass without comment. Silence may reflect a quiet confidence, but that may be misplaced.

Military action was taken after the devastating events of 9/11. A powerful coalition of nations stood against a belief system that mobilises the murder of those who hold the values of tolerance and liberty. Inaction was not an option. We acted in national self-defence to build a sustainable, democratic government in a more secure land. This was not about nation-building, but about preventing Afgh- anistan from again becoming an incubator for extremism. Our aim is not to build Hampshire in Helmand, but it is, in part, to ensure that Helmand does not come to Hampshire. Al-Qa'ida has been severely weakened and the achievements, for example the size of the Army, are real. Progress, however, is not irreversible.

Serious challenges remain. Western nations are unilaterally announcing divergent dates for withdrawal. There has been a collapse of US-Pakistan and Kabul-Islamabad relations. The recent Bonn Conference was widely perceived to be a failure. A recent Nato study of interrogations of Taliban prisoners starkly outlined their strength. Examples of deadly infiltration of Afghan forces are increasingly familiar, and there is widespread worry they are ill-prepared to take responsibility for the security of whole country, as well as that of British non-combat forces post 2014.

There are some, including this newspaper, who argue that we should have withdrawn by now. While I do not doubt the sincerity of that demand, I doubt its merit, and we agree with the timetable that has been set. Early withdrawal would be as dangerous as a "cliff- edge" departure, which could threaten the nation's fragile fortunes. It is a real worry, therefore, that the Government has moved from a conditions-led to calendar-driven withdrawal strategy. While endorsing the date for the pull-out, we do not endorse the passive manner with which it is being approached by ministers. There is too much to be done between now and 2014. Post-2014 planning rather than the pace of our exit will determine success.

As Douglas Alexander, the Shadow Foreign Secretary, has argued, there must be clear political strategy to match military might. Too much, however, remains unknown. The nature of the pledged "commitment" from the international community, the size and scope of a residual Alliance force, Afghan government funding and the role of regional nations in stabilisation, in particular Pakistan, are all ill-defined. The Government must re-establish the diplomatic leadership role that Labour bequeathed them.

An exit strategy is not a political strategy. Afghanistan needs twin internal and external political settlements, driven by the United Nations. Internally, this must be inclusive and involve the reintegration of ex-combatants as well as legitimacy for tribal and ethnic groupings. This means negotiating with the Taliban; their recent public declaration that they will hold talks with the US is a breakthrough.

This is painful, especially for those who have lost loved ones. We must demand a denunciation of violence and an endorsement of the principles of the constitution, but there will be no peace without a settlement reflective of a diverse nation. The Taliban are not a homogenous block but multiple factions and insurgents united by sometimes divergent grievances, often driven as much by practical concern as ideological belief.

An external settlement means establishing a regional framework that respects Afghanistan's stability and sovereignty. Regional partners must recognise that Afghanistan can never again be another nation's proxy and that they have a shared interest in its stability, since the reverse can destabilise the region.

The Afghan government faces major challenges, from insurgency and cross-border terrorism to the degree of corruption within government, which demand our engagement. David Cameron must put these issues at the top of the agenda of his forthcoming meeting with President Obama; he must also articulate a clearer plan before May's Nato summit in Chicago.

We supported government action in Libya because it was the right thing to do, but military success in Libya should not overshadow our decade-long main mission which is being served by 10,000 of our men and women in Helmand. Grotesque events in Syria demonstrate the complexities of international influence and interventions and rightly dominate ministerial minds, but should never be at the expense of attention on Afghanistan. The public are entitled to know the facts. Not talking about these challenges does not make them any less pressing.

It should be the Prime Minister and not only the Opposition who discusses with the country why this remains a mission in the national interest. It is vital to our national security and that of the region. It cannot become the forgotten war.

This is a defining moment for defence policy. Afghan withdrawal, the financial crisis, emerging threats and new economies combine to mean the Arab spring is potentially the tip of the iceberg of the change we will experience. This demands more than the strategic shrinkage by stealth that the Government offers. Labour has just launched a year-long defence review to examine the drivers of global change, the impact on security and our military structures.

We must learn lessons from Afghanistan for defence policy. The prosperity, security and liberties of those at home cannot be separated from events beyond our borders. A belief that you have responsibility beyond your borders is not just ideological, but, as has been powerfully demonstrated recently, a necessary response to the world in which we live. To retain an interventionist defence posture, however, we must improve pre- and post-conflict planning, with an emphasis on coalition-building, empowering local populations and co-ordinating defence development.

Communication is also vital. I worry that the legacy of recent conflicts is that one-and-a-half unpopular wars may create a permanently unpopular concept of intervention, and yet the rapidly changing security landscape means an ambivalence to defence and security policy would undermine our interests and values.

A consensus with the country and bipartisan unity must be earned. That is why the Prime Minister must communicate the case to the country and become more statesman than spectator. British troops deserve a strategy to match their extraordinary bravery and professionalism.

Jim Murphy is MP for East Renfrewshire and Shadow Defence Secretary

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments