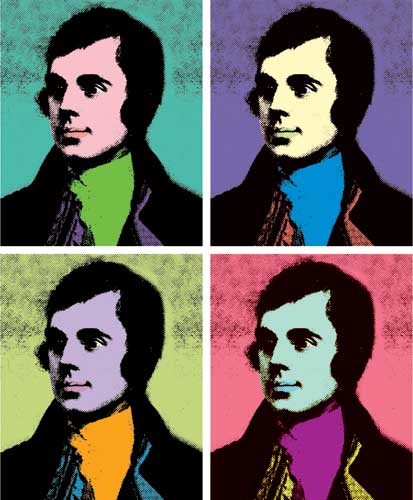

Hardeep Singh Kohli: Burns speaks for a Scotland that forges its own future

Today, as the world celebrates 250 years since his birth, the poet who refused to blame all his country's woes on the English is still the voice of a nation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last Wednesday night, a friend and I curled up in front of the TV and enjoyed Billy Wilder's beautifully written, elegantly conceived movie The Apartment; Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine at their finest in the golden age of American cinema. About an hour and a half into the film the work of Robert Burns appears. Astonishing, eh? During the New Year's Eve scene when MacLaine's character, the sparky Miss Kubelik, realises that she loves Lemmon's idiosyncratic C C Baxter rather than her manipulative boss and runs through the Manhattan streets to be with him, the crowd is singing "Auld Lang Syne". (Given his romantic poetry credentials, the Bard would surely have approved of Miss Kubelik's behaviour.)

Few poems are more commonly recited than Burns's work, which is rolled out every New Year's Eve across the globe. I would wager that the overwhelming majority of those who cross their arms and link hands with their companions have little or no inkling that the man behind the song was a Scottish Lowland farmer and excise man who died in abject poverty at the tender age of 37. And that was just the beginning of the man's talents.

Yet you would be forgiven for not knowing it, even as a Scot. Growing up in Glasgow in the Seventies and Eighties, I was barely taught Burns at school. There was the odd poem here and there; a wee bit of "Tam O'Shanter"; a lesson on "My Heart's in the Highlands"; but there was very little that celebrated the greatness of the man and gave him his rightful place in the pantheon of European literature. I remember my professor of Scottish Literature, the inspirational Rod Lyall, being utterly astonished that by the time we arrived at university we had been more thoroughly schooled in the work of the great Bard of Stratford than in the national Bard of Scotland. He soon put that right.

It was as if the educational establishment in Scotland's schools was embarrassed by his work. It was fine for us to read the politics of Orwell, to be immersed in the satire of Huxley, or to be asked to appreciate the romance of Tennyson; we were given fully rounded literary educations in almost everything, yet we were never allowed to enjoy the breathtaking breadth of Burns.

The word prolific is used and abused these days. As is the phrase, Renaissance man. Burns was truly prolific, truly Renaissance in his outlook. He wrote in Scots, the old language widely found in eastern Scotland. He wrote romantic verse, political satire, songs and ballads; he collected, collated and updated the folk songs of Scotland, introducing them to a new generation. He is also credited with saving the Scots language from falling into disuse and bringing national pride back to the people. This is made yet more impressive when one realises that Burns was pretty much home-schooled by his father, receiving little or no formal education. By the age of 15 he was a full-time farm labourer, and a Lothario, bedding anything that moved and siring a smattering of illegitimate children. (His first was born to his mother's servant: stylish).

Burns was truly a man of the people, a farmhand who turned his hand to verse to woo the women. He wrote from the heart, and was able both to communicate to the common woman and man and to turn the heads of the literary establishment.

It has always perplexed me that he never seems to garner the credit he deserves in Britain. He is described as a Scottish poet; Shakespeare is seldom described as an English playwright. I have read and studied five Shakespeare plays; errant pupils at my Jesuit school in Glasgow were required to copy out Shakespearean speeches any number of times (which explains my expert knowledge of so many soliloquies from Hamlet). Shakespeare's brilliance is shared across this rickety collection of kingdoms that we refer to as "United", whereas Burns seems woefully overlooked outside Scotland. Having said that, Burns's work is well known in wider Europe; the Russians and Ukrainians, for example, respect and admire his work, celebrating it and giving it the prominence it deserves.

It's difficult to explain why Burns has been so singularly snubbed in England. It is exactly this sort of cultural ignorance that makes Scots feel marginalised by their English neighbours. Ironically, the pettiness that often abounds in the minds of the Scots when it comes to their troubled and troubling relations with their older, stronger sibling, were at the heart of my favourite Burns poem.

Let me explain. Scottish history is strewn with moments of what might have been; we live our lives ruing our ill fortune and our bad luck. The Treaty of Union 1707; Culloden 1746; Argentina 1978. Burns was born some five decades after the Treaty of Union, when the impact of the legal and political subjugation of Scotland was still strongly felt. It was the fashion of the time (a fashion that has since become a habit) for Scots to blame the English for the Treaty of Union, for all the ills of the Scottish people and the nation. England was a convenient scapegoat for Scottish failures. Burns, however, railed against this exoneration of personal responsibility.

In his coruscating, bitingly satirical, political diatribe "Such a Parcel of Rogues in a Nation" he does refer to the Scots being "bought and sold for English gold", but he lays the blame squarely at the feet of the Scots. The rogues he refers to are his fellow countrymen, those Scots who were falling over themselves with eagerness to please the English, those Scots that were complicit in the pact, those Scots who were art and part in the sale of their nation to the English.

And in 2009, 250 years after his birth we Scots would do well to remember that sentiment. The English, as I have discovered first hand, are not our enemy. Some of us Scots believe that the English nation has nothing better to do than to cause us distress and upsetment. Nothing could be further from the truth. Much as we would like to think that we are of such seismic significance in the collective English psyche, in truth we are but an irrelevance to the English; we are a beautiful, small "region" abutting the North of England; we drink too much, are generally friendly, and enjoy deep fried food. When you ask most English folk what they think about the Scottish nation they rarely have an opinion; we are fairly forgettable. Burns had this notion nailed more than 200 years ago. It's time we re-engaged with it.

Sir Walter Scott met Burns at the age of 16 and was highly impressed. It was less than 10 years before Burns's death. One can only wonder what might have happened had Burns lived to inspire Scott and the next generation of Scots writers. Nonetheless, Burns's legacy lives on. Of the many glowing tributes that have been paid to the Bard, in my opinion the most accurate testimony is that of John Stuart Blackie, the 19th-century Scottish scholar and lecturer. He characterised Burns's contribution to Scotland and the Scots thus: when Scotland forgets Burns, history will forget Scotland.

I, for one, will never forget Burns.

Such a Parcel of Rogues in a Nation

Fareweel to a' our Scottish fame,

Fareweel our ancient glory!

Fareweel ev'to the Scottish name.

Sae fam'd in martial story!

Now Sark rins o'er Salway sands,

An' Tweed rins to the ocean,

To mark where England's province stands –

Such a parcel of rogues in a nation!

What force or guile could not subdue

Thro' many warlike ages,

Is wrought now by a coward few

For hireling traitor's wages.

The English steel we could disdain,

Secure in valour's station;

But English gold has been our bane –

Such a parcel of rogues in a nation!

O would, or I had seen the day

That Treason thus could sell us,

My auld grey head had lien in clay

Wi' Bruce and loyal Wallace!

But pith and power, till my last hour

I'll mak' this declaration :-

We are bought and sold for English gold –

Such a parcel of rogues in a nation!

Robert Burns (1759-1796)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments