Hamish McRae: What would the Republicans do with the US economy?

Romney plans to cut federal spending to a little over 18 per cent of GDP by 2023

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Would the Republicans really be different – or more precisely, would US economic policy really be different with Mitt Romney as President, rather than Barack Obama? It is a question that we certainly have to contemplate and the events this week should focus our minds.

But, as always with such questions, you have to make a clear distinction between what politicians say before winning office and what they do once they are elected. The most recent example of this is François Hollande squeezing French fiscal policy more tightly than his predecessor did, notwithstanding his campaign promises. So you have to be careful.

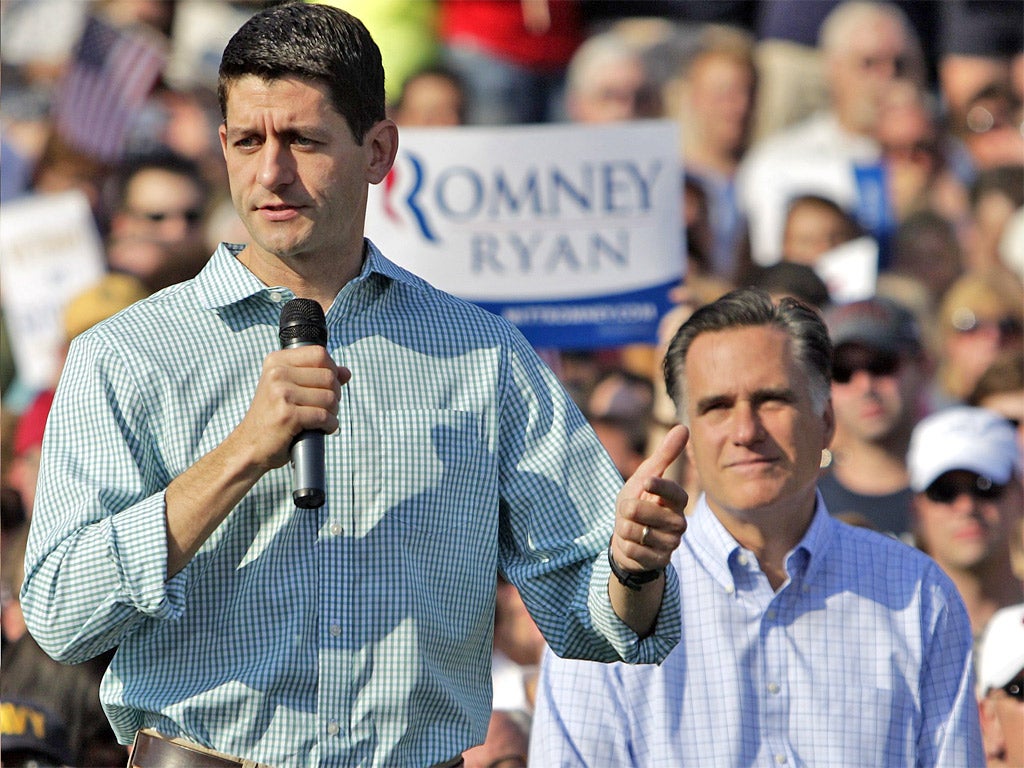

That said, there are some glimpses of the direction the Republicans might head to be gleaned from the "Path to Prosperity" plan, prepared by vice-presidential nominee Paul Ryan, passed by the House of Representatives last April and then rejected by the Senate. The most recent version cuts spending, cuts taxes, and cuts the deficit. Quite how spending cuts are to be established is not clear, but the target is to cut federal spending to a little over 18 per cent of GDP by 2023. That compares with about 22 per cent at the moment but would be about the same level achieved by President Clinton by the end of the 1990s.

If these numbers seem very low to anyone here or in the rest of Europe, the explanation is partly that our numbers usually include all public spending, not just that of the central government, and state spending in the US bumps these numbers up considerably. You also have to adjust for healthcare, which in most of the world goes largely on the public budget, whereas in the US is only partly on it.

On the revenue side, under these Ryan plans, federal taxes would take a little over 18 per cent of GDP by 2023, which would leave the country with a modest running deficit. This would, however, be somewhat higher than the present US tax take, which at a federal level is running at only about 15 per cent of GDP. Tax rates would be cut to a top rate of 25 per cent for both income tax and corporation tax, the theory being that lower rates will bring in more revenue.

Independent estimates suggest that under this plan revenues would stabilise at a lower proportion of GDP, perhaps around 15 per cent – so to get to the 18 per cent figure, the next administration would have to close a large number of loopholes. That apparently is the aim, but the gap to be closed is big. President Obama's plans, by contrast, see revenues rising to just under 20 per cent of GDP, with spending coming down to 22 per cent.

What should the outsider make of all this? On the face of it, the choice is rather discouraging. We have a president who inherited a catastrophically large deficit, at around 11 per cent of GDP, but whose efforts to cut it have been ineffective. And we have a challenger whose numbers are difficult to reconcile. And under both sets of proposals, the country is still running a federal deficit equivalent to 2 per cent of GDP in 10 years' time. Meanwhile, there are automatic tax increases that will come in at the end of the year, the so-called fiscal cliff, if Congress does nothing. Oh, dear.

Two things make me more optimistic than this outline would suggest. One is that in the past the US has pulled back from fiscal disaster and corrected itself, most recently under President Clinton. The other is that the dynamics of fiscal policy will change after the election, whoever wins.

If governments can borrow very cheaply, they will. For the moment, the US and other "safe haven" governments can borrow at below the rate of inflation. But this is abnormal, indeed unprecedented in peacetime. So rates will rise – and that will force a change in policy, perhaps not before time.

A very rocky detour from the Rockies

For anyone interested in skiing, Jackson Hole is a decent Wyoming resort, not huge by Alpine standards but with some tricky black runs and, of course, the brilliant powder of the Rockies. For anyone interested in the world economy, however, it is a conference of central bankers, hosted by the US Fed, that takes place every year at the beginning of September. Bankers gather there later this week.

So there will be great attention paid to what Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, says on Friday. Will he hint that there will be another bout of quantitative easing? What will be his judgement on the state of the US economy?

There would also have been keen interest in anything coming from Mario Draghi, the chairman of the European Central Bank, which next week is expected to announce how it will cut the cost of finance in the weaker eurozone economies. Its key meeting is on 6 September.

Alas, there will be no leaks from Dr Draghi – for the simple reason that yesterday he suddenly cancelled his trip. The reason? A spokesman said it was "because of the heavy workload foreseen in the next few days".

But they must have known the calendar for months, so that does not really wash. So maybe the uncertainties as to what on earth the ECB can do are even greater than most of us thought.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments