DJ Taylor: Who really is running the show?

Obama's visit was a three-ring circus that told us precisely nothing about where power actually resides

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Inspecting the photograph of Messrs Obama and Cameron dishing out burgers in the garden of No 10, and scanning the week's other big stories about super-injunctions and rising food prices, I found myself remembering a song written by my all-time favourite rock lyricist, Magazine's Howard Devoto.

The number in question, called "Back to Nature" and recorded in the late 1970s, features a line in which the singer insists that he "wants to walk where the power is".

A promising line of enquiry this past century and more, the urge to work out "where the power is" has an extra-special resonance here in 2011. The Victorian novelist who sat down to establish which particular forces – social, economic, political – held his characters in thrall generally had not the slightest difficulty. The Queen sat on her throne; the landowner frowsted in his baronial fortress beyond the hill; and the upstart industrialist's Brobdingnagian factory was busy polluting every trout-stream in the county. The life of certain Victorian citizens might have been nasty, brutish and short, but at least one knew who was doing the brutalising.

A century and a bit later, you have an idea that power has grown at once more concentrated and more anonymous. Who decides if my country goes to war or stays at peace? My democratically elected government, surely, although that doesn't quite explain the existence of the USAF base down the road. Who decides if I shall eat or starve? This one is even trickier. Tesco? Some commodity broker gamely taking a punt on a rise in grain prices? The rule – or rather the murkiness of the influences at work – applies to even so abstract and diffuse a phenomenon as "taste". Who, for example, now exercises the greatest control over the nation's reading habits? Why, a cyber-book warehouse (Amazon) and the Russian oligarch who has just bought Waterstone's.

None of the above, by the way, is a complaint about accountability. There will always be oligarchs, and Victorian society was approximately as democratic as the process that selects the Manchester United starting XI. On the other hand, one likes to be able to identify one's oppressor. Half a century ago, my father had no great opinion of Basil Robarts, chief general manager of the Norwich Union Insurance Society, as it then was, but at least he knew where he lived and saw him in action. Rather than handing out burgers in Downing Street, the people who really run the world are probably hunkered down in silos somewhere in the American Midwest: devious, conspiratorial and entirely unknown to the billions of people they indirectly boss about.

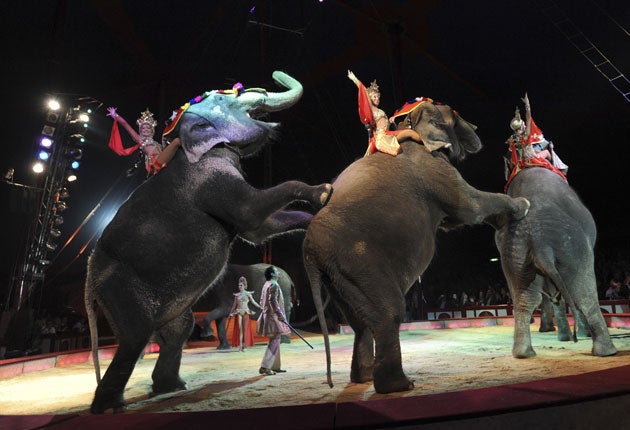

According to "Whitehall sources", a group of MPs is planning to overturn the Government's much-criticised refusal to ban wild animals from performing in circuses. Apparently, backbenchers from all parties will attempt to force a special Commons debate on the issue next month. A vote in favour is confidently expected, and the Conservative MP Mark Pritchard has called for the Government "to do the right thing; end this antiquated, cruel and barbaric practice, and listen to the voice of the British people".

If a social historian were to compile a list of our most estimable national characteristics, then a concern for the welfare of animals would stand fairly high on the list. One of the more civilised aspects of contemporary Britain, after all, is that – by and large – we don't bait badgers or grind up superannuated donkeys into dog food. All the same, I can't remember the last occasion on which the Commons convened an emergency debate on child poverty, or people trafficking, or the imprisonment of infant asylum-seekers.

The nation's cultural propagandists received a welcome boost this week, with a Norwegian report suggesting that visiting an art gallery, a museum or a theatre has a beneficial effect on the visitor's health. Having questioned 50,000 people about their health and susceptibility to depression, the survey's compilers concluded that cultural activities were good for both genders, with men appearing to benefit more. Apparently satisfaction levels will be higher if the men involved are creatively inclined.

Leaving aside the last point, which struck me as rather obvious, one feels that the efforts of certain institutions to promote themselves are rather disingenuous. I have listened to several sermons, for example, in which the preacher has assured his congregation that people who believe in God feel happier and live longer.

But surely, one looks at a painting or visits a museum out of that elemental desire to see oneself in some kind of wider and illuminating context, just as (presumably) one believes in God to ensure eternal salvation. And all this ignores the fact that certain kinds of art, like certain kinds of religion, are designed to lower the spirits. As the rock critic Charles Shaar Murray once remarked, of some 1980s heavy metal group whose singer declared that the blues "were gonna get you down", did anyone expect that the blues were going to get you up?

The celebrated American chanteuse Dolly Parton turned up on one of the celebrity websites lamenting the difficulties involved in wearing a wig. Ms P, a long-term devotee of the extension, confessed to a number of embarrassments, including leaving a clump of ersatz hair in the branches of a tree while out cycling with a friend, and, while on stage, allowing a flowing tress or two to get caught up in her fiddler's strings. "I was fighting to keep it on," she admitted.

Ms Parton's amused self-deprecation suggests that, unlike physical disability, or stammering – which no comedian south of Frankie Boyle has been able to touch for decades – hair-pieces remain one of the great comic staples. Just as 19th-century novels abound with juvenile old men burdened by the nickname "Wigsby" and jokes about grim-faced middle-aged ladies affecting what were known as "Madonna fronts", so any modern pantomime dame can still raise a laugh by abstracting somebody's toupee. But for how long? It can only be a matter of time before some wig-merchant complains that their human rights are being infringed, or detects malice in what is one of comedy's most time-honoured perceptions – the gap between stylist's illusion and bald reality. One doesn't have to be a cultural purist to think that when wigs, like adultery, mothers-in-law and lodgers, cease to be funny, then British comedy will have ceased to exist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments