DJ Taylor: Secretive celebrities are always with us

The superinjunction is just part of a long tradition of hypocrisy in public figures, and why doesn't the BBC pay (me) more?

GK Chesterton died as recently as 1936, but to read Ian Ker's new life of him (GK Chesterton: A Biography) is to be reminded of the enormous gap that separates the world of a century ago from our own.

One of Chesterton's many attractions to the modern reader is that he was a genuine democrat, rather than a pretend one, who believed not only in giving ordinary people the vote but – an altogether different thing – taking the trouble to investigate their opinions on the great issues of the day.

This naturally led him to prefer what he called "vulgar comic papers" to high-brow journalism on the grounds that the former "are so subtle and true that they are even prophetic". It seemed obvious to him – a really startling deduction, this, for 1908 – that "the literature which the people studied" was much more interesting than the kind of sociological literature "which studies the people". An historian could gauge the social tenor of Great War-era England better from a copy of Tit-Bits than some early numbers of the New Statesman and Nation.

Bracing as all this is, it is worth noting that it was written when there was still such a thing as popular culture, and before the mass-cultural elephant got its foot firmly on the average person's neck. And so the "wisdom" Chesterton detects in street-level humour comes sui generis rather than being imposed from on high. Given the infallible optimism of the Edwardian democrats, you wonder what they would have made of the social arrangements of the early 21st century. How, for example, would Chesterton, a defender of extended pub opening hours, have felt had he been set down in the Prince of Wales Road, Norwich, at 3am on a Sunday, or, as an advocate of the people's right to enjoy themselves, contemplated the zombie-strewn panorama of the average Game store? You feel he might, at the very least, have diagnosed a serious disconnect between what people want and what the people's manipu- lators think they ought to have.

***

To read the accounts of Tuesday night's last-minute scramble to reach the Olympics ticket ballot – a feeding frenzy so intense that the deadline had to be put back from midnight to 1amWednesday – was to be struck by the the stranglehold that technology exerts over us, and its denial of choice to the substantial part of the population that disdains its blandishments. For a start, applications had to be made online, which excludes something like a fifth of the community. Then again, attempts to reach the ticket ballot had to be supported by a Visa card. Fine if you have this amenity, but a serious impediment if you don't.

It could be argued, of course, that any non-browser or card-holder could surmount this obstacle by enlisting better-placed friends. On the other hand, why should an event supported by the taxpayer and designed to be as "inclusive" as possible be administered solely to suit the technological convenience of the organisers? Would setting up an office to process applications by cheque have cost so much? Even now, one nervously awaits the headline announcing that the site has been hacked and six million sets of personal data are floating around in cyberspace.

***

In a week enlivened by news of "super-injunctions", and Andrew Marr's former dalliance, it was hard to ignore one or two of the historical parallels. You are a public figure of the late 1850s, let us say, anxious to keep details of your extra-marital doings out of the newspapers. How do you go about it? The answer is that, by and large, editors will do the work for you, and should any injurious gossip look as if it were about to leak out, well-situated friends will queue up to fight proxy battles on your behalf.

This, at any rate, is what happened in the celebrated "Garrick Club Affair" of 1858, when Dickens, enraged by his arch-rival Thackeray's (inadvertent) blowing of the gaff on his relationship with Ellen Ternan, embarked on a war of attrition that only ended a few months before Thackeray's death in 1863. The thought that a public which admired a series of novels built on the sanctity of marriage might be entitled to hear about their author's dishonouring of his marital vows seems not to have occurred to Dickens, just as it never seems to occur to the modern celebrity who engages Mishcon de Reya "for the sake of the children" that publicity is a two-edged sword.

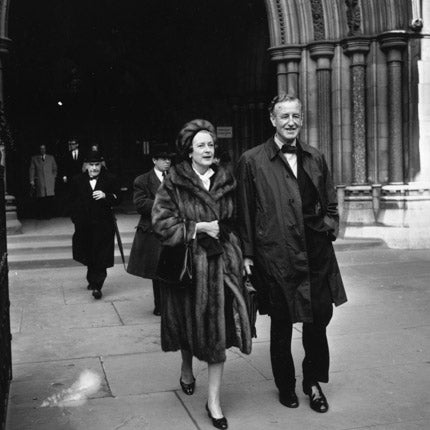

The odd thing about this reluctance of well-known people to call a spade anything other than a large blunt instrument for shovelling dirt is that it exists at almost every level of intellectual debate. Browsing through Anthony Powell's journals the other day, I came upon a dilemma that exercised several of Powell's friends in the mid-1980s. Should they release the "deliberately spiteful" letters written by Ian Fleming's wife, Ann, to the man compiling a volume of her correspondence? But surely, if Mrs Fleming wrote spiteful letters then, to be truly representative of her no doubt complex personality, a collection ought to contain some of them? But there are probably still Elvis fans who refuse to believe that the great man took drugs, gorged on junk food, and died on the toilet.

***

There was an affecting story on the front of last Wednesday's Daily Telegraph about the BBC's difficulties in recruiting the high-calibre personnel it needs to steer the corporation through the choppy waters of government cuts and satellite competition. According to the Director-General, Mark Thompson, some posts at the £400,000 per annum level are unfilled and "remuneration is an issue".

My first thought was: how much money do you need to lead the luxurious life style which senior media figures seem to regard as a birthright? My second thought was that it is a pity that the corporation's freehandedness with executive salaries couldn't be extended to some of its output. A morning's filming for BBC4 might bring in £200 – not too bad on paper, but ignoring travel time and the substantial amount of research that is likely to be involved. As for radio, one sometimes ends up emailing the producer for whom one has laboured with the plaintive enquiry: "Will I get paid for this?". As a general rule, the parts of the BBC that make the best programmes are those with the least money. At least the ones that make the worst programmes look as if they are suffering the biggest cuts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments