DJ Taylor: Ain't what you got, it's the way you use it

Identifying hard truths on class and union disputes... and knowing when to die and when not to wave your wallet

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the wake of a survey suggesting that 71 per cent of the UK population believes itself to be "middle class", and talk of a Budget-enhanced squeeze on the bourgeoisie, social categorisation appears to be as hot a topic as the Libyan air strikes.

What does it mean to be middle class? None of the pundits bidden to address this enticing subject seemed quite to know. Clearly a social grouping that includes three-quarters of the Cabinet as well as a shabby-genteel pensioner living off capital has become so elastic as to be in grave danger of losing its utility altogether.

The telescoping of the British middle classes is a fairly recent phenomenon. Back in the 1890s it was a great deal easier to define yourself against the demographic landscape of which you were a part. Mr Pooter, The Diary of a Nobody's harassed clerk, is indisputably a middle-class tribune in an era when to be middle class actually meant something: keenly aware of his status in the hierarchies of the workplace, ever hopeful of the prospects of his rackety son, quietly furious whenever his personal dignity is compromised.

One hundred and twenty years later, all that remains are social gradations so subtle that half the people caught up in them would scarcely know they were there. George Orwell once described himself, with painful accuracy, as belonging to the "'lower-upper-middle class". As the remote descendant of an earl he belonged to a cadre that was theoretically able to hunt, shoot and employ servants but in practice could no longer afford to do so.

Working from this template, I should categorise myself as belonging to the upper-lower-middle class, Oxbridge education and upward mobility never quite cancelling out the memory of my father's escape from the council estate. The touchstone of one's precise standing in relation to the middle class, by the way, is not how much money you earn but your attitude to it. The difference between my father and my mother was that the former knew his salary to the last penny, while the latter had to look it up on her pay slips.

***

On Thursday morning, approaching the University of Ulster's Coleraine campus, I found myself confronting an altogether novel dilemma. Should I cross a picket line? The line in question was staffed by members of the university lecturers' union protesting about changes to their pension arrangements. I belong to a political party that, so far as I can make out, supports their cause. But there were a couple of dozen students waiting in a lecture theatre for me to enlighten them on "the future of the book". What was I supposed to do?

Clearly all this had the makings of a special edition of The Moral Maze. Brought up in an exemplary 1970s middle-class household (see previous item) where "strikers" were regarded as more or less on a par with plague-rats, and the world-weary habitué of a profession in which you can be sacked by email, my instinct was to march straight across. This was instantly countered by a suspicion that in a world whose big battalions grow bigger by the minute, only solidarity will see us through. Plus, there is simply nothing to be gained by expressing one's individualism in the presence of a handful of innocuous-looking university lecturers. Forging a path through their meekly lofted placards, I reflected that if they had been Arthur Scargill and his miners the gesture would have had some point.

***

For all the lavish obituaries, and the sight of film critics of a certain age almost prostrate in the dirt, one couldn't help feeling that Elizabeth Taylor had picked the wrong day to die. Certainly by Wednesday evening, amid a crowded schedule that included the Budget and further conflagrations in the Middle East, news of her death had sunk to the 10th item on BBC Ceefax.

You always sympathise with the distinguished cultural figure whose misfortune it is to shuffle off the planet on a day of cataclysm. It was the bad luck of both C S Lewis and Aldous Huxley to die on the day of the Kennedy assassination, when both The Chronicles of Narnia, inset left, and Brave New World counted for nothing. Then there is the indignity of being crowded out by fellow practitioners in one's particular field. Some years ago a newspaper rang to tell me that the novelist J L Carr had died. It was a slack day for deaths: only 1,500 words, I deposed, could do justice to Carr's achievement. Half-an-hour later the phone rang again. "Apparently Sir Harold Acton's just died," came the voice of the obits editor, "so could you just do 800?" There was no point in suggesting that Acton was possibly a gilded drone who got where he did by dint of his exalted connections, and that Carr's was the genuine talent. Sir Harold had his 1,500 words and Carr was relegated to the decent obscurity of the bottom half of the page. As to the relative achievements of John F Kennedy and C S Lewis, I'd say the jury was still out.

***

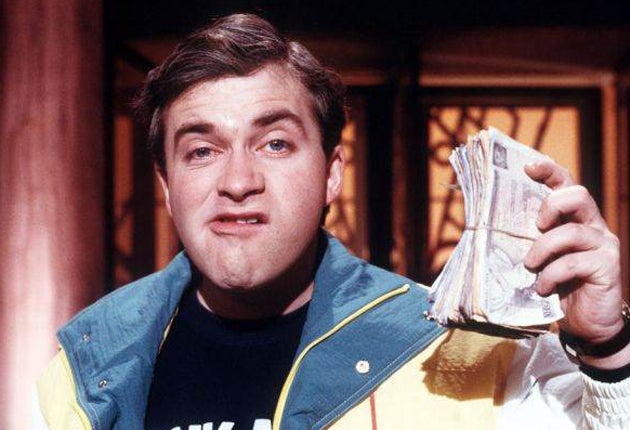

Though not the most regular reader that the Daily Star ever had, I did spare a moment for its account of the party held earlier this week by the England football squad. This shindig apparently went on until 4.30am, was attended by at least one of the players' mothers and featured a squad member waving a wad of banknotes at an admiring photographer.

The brandishing of money as a way of demonstrating moral or economic superiority is, of course, an elemental gesture. Harry Enfield maintained that he got the idea for his Loadsamoney character from Chelsea fans whose amiable habit it was to taunt rival supporters in the north of England by holding up their wallets. More civilly, Evelyn Waugh, when treated to lunch by the young Peregrine Worsthorne on behalf of The Sunday Telegraph, complained that the port was not of a kind which the proprietor's wife would wish him to be offered. "But it is not Lady Pamela who is offering it to you," Worsthorne replied, meaning that he was paying for the meal himself. "My dear fellow, I had no idea," Waugh replied, letting a shower of £5 notes descend over his host's head.

Going back to the vainglorious wad-flasher of the England squad, one couldn't help remembering Alan Ball's account of being summoned, on the morning of the 1966 World Cup Final, to fetch the £2,000 owed to his room-mate Nobby Stiles and himself by the sponsors, Adidas. So little did the money mean to them that Ball eventually threw it in the air and watched the notes cascade over the bed like confetti, whereupon "we laughed like kids". There is a moral here somewhere.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments