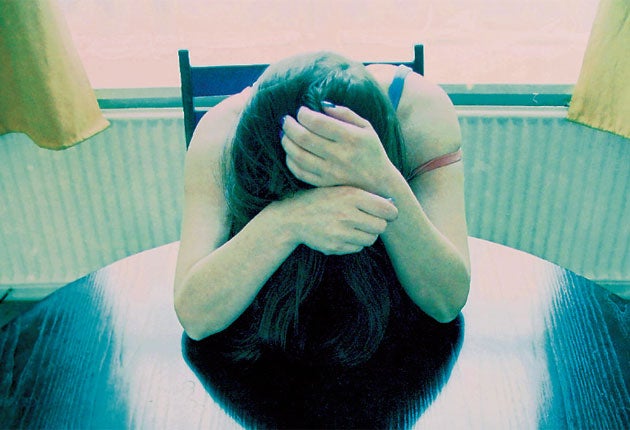

Carol Sarler: There's nothing 'special' about rape

Defendants should not be granted anonymity. Rather accusers should be treated like other victims of violence and named

Tucked within last week's new government plans lay one apparently innocuous crowd-pleaser: the proposal to extend anonymity in rape cases to include not only the accuser but, at least until conviction, also the accused. For the past 20 years outrage has been expressed whenever innocent men have had their names and reputations dragged publicly through arduous court proceedings – prominently, for instance, Austen Donnellan in 1993, Ashley Pittman in 2000, Warren Blackwell in 2006 – while their mendacious accuser rests untarnished in her privacy.

That it seems unfair is easy to argue; that it deserves redress easier still. But if the outrage really is provoked by simple imbalance, by the perception of an unevenhandedness in the treatment of two people who are supposed to enter the legal system on equal footing, there is another way of achieving that equality: remove the anonymity granted to the accuser.

It is, after all, her anonymity and not his exposure that is anomalous within the law. The guiding principle of British justice, one that has stood us in decent stead since Magna Carta, is that an adult faces his or her accuser in open court for all – an "all" that now includes the reporting media – to hear. It is a principle we cannot mess with lightly; closed trials instigated by shadowy, unknown accusers are the stuff of regimes we correctly fear, and to extend the cast of unknowns in the name of fairness runs the real risk of eventually achieving the exact opposite.

That the principle ever was messed with owes much to the thinking of the 1970s when anonymity was introduced. Many people, especially those active in the flourishing women's movement of the time, were concerned that rape was an under-reported, under-punished crime – funny how little things change – and believed that anything likely to assist women through the procedure that followed making formal allegation could only help; in other words, it was believed to be a pro-women measure.

And maybe, just maybe, it once did smooth the path for some women who, in those more buttoned-up times, would have found keeping quiet preferable to describing "down-there" assault. But here, in intimacy-overloaded 2010, with added cushioning tools such as video evidence links, it is hard to accept that the sparing of a few blushes is a price worth paying for something that has turned out not to be pro-women at all.

Consider: if a woman is beaten senseless, has most of her bones broken, is stripped naked, bound and gagged, tied to a chair and left in a burning house to die (this is not an imaginary scene; it happened not so very long ago), and if she is rescued in the nick of time and her attacker brought to trial, she is – indeed, was – expected to give evidence in full public gaze. Do we really believe that it was easier for her to "relive the ordeal", just because intercourse did not take place, than it is for another woman, whose boyfriend became drunkenly abusive one night, and intercourse did? Do we really believe that the first woman's courage in complying with due judicial process need not be asked of the second woman because she is, somehow, more "special"?

If that is the belief that underpins the rules, it does little to advance the progress of justice in rape – still under-reported and under-punished – and a great deal to demonstrate disturbing attitudes towards rape itself. First, to accept that the treatment of an alleged victim may be different from that shown to the alleged victim of any other violent crime is to suggest that the crime itself is fundamentally different. God knows, after all that has been said and written over the years, we should have got the message by now: it is not. Rape is not a crime of lust or passion or misplaced sexual desire; rape is just another crime of violence, humiliatingly perpetrated by the physically stronger over the physically weaker.

If those waters are muddied by concentrating overly on the manner of the attack, we move in a heartbeat from genital to sexual to "sexy" and from there to the widespread, prurient fascination that the victims wanted to avoid in the first place.

Second, if rape is allowed to be treated as different from (and, usually, worse than) any other crime of violence, it panders to a view that a penis is the most powerful of all bodily weapons and therefore asserts an authority to those in possession of one. No doubt this is a view cherished by men of a certain type – but, surely, not by women? If I am any measure of my kind, I am much more frightened of a bludgeoning fist or a maddened, kicking boot than from any shape or size of willy run amok. While I would not care to be on the wrong end of any of them, I fail to see why I might be expected to describe the awfulness of an assault by fist or foot yet permitted an attack of the vapours if asked about an assault by the third. It assumes a female fragility that is insulting: by his genitalia he is made strong, by my genitalia I am made weak.

Nobody would wish to underestimate the rigours of a trial, the months of anticipation, the cross-examination with which to contend and a verdict that might not go your way. But this does apply to both accuser and accused; a grisly time is had by all. And if the new government proposal does come to pass, the (usually male) accused will come to discover what the (usually female) accuser already knows: the granting of anonymity is, in the end, only window-dressing. It doesn't work. The only people one really cares about – family, friends, colleagues and extended social circle – all know anyway. They know the name of the "Miss B" whose evidence they read in the local paper just as certainly as they will know the name of the newly-anonymous "Mr C" who attempts to counter it.

If we want even-stevens, then by all means let us have it. But instead of creating yet another legal anomaly on yet another dangerously steep, slippery slope, parity would be more wisely achieved by removing the anomaly we already have.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments