Andrew Grice: A Prime Minister whose personal brand is bust

Inside Westminster

"People don't care where you came from," David Cameron told me. "They do care where you want to take the country." It was 2005, and we were chatting about his background and his family during his successful bid to win the Conservative Party leadership.

His remark revealed his sensitivity about his privileged upbringing and whether it might be a barrier to him becoming Prime Minister. It became a well-used Cameron soundbite.

At the time, I believed Mr Cameron was right. Although some Labour figures always ache to re-fight the class war, it leaves ordinary people pretty cold. But there was a caveat: his policies in opposition and actions in government if he got there would need to dispel any lingering doubts that he was a "Tory toff". As well as having to detox the Tory brand, Mr Cameron had to de-toff his personal brand. The two goals dovetailed neatly into his modernisation project.

It worked well in opposition. But not quite well enough to win the overall majority the Tories should have won in 2010 against Gordon Brown's exhausted administration. When Labour tried to play the class card against the Bullingdon Boy, it seemed to backfire. The voters had moved on.

There were occasional glimpses of Mr Cameron's sensitivity; he was reluctant to be photographed in a white or black tie, preferring to wear a lounge suit to City of London dinners and weddings. Privately, he now suspects that the detoxification of the "nasty party" had not been completed by 2010, as he had hoped. Despite the setback, coalition with the Liberal Democrats appeared to offer a way to complete the project: he had, after all, billed himself as a "liberal Conservative". The votes of 57 Liberal Democrat MPs allowed him to ignore the siren voices on the Tory right howling for the party's traditional policies.

For the Coalition's first 18 months, it seemed to work. But since the turn of this year, the image of Mr Cameron and his government has changed. Andrew Cooper, the Downing Street strategy director and polling guru, now reports that the voters' top concern is that the Coalition is "out of touch". Nadine Dorries, the outspoken backbencher, was accused of disloyalty after branding Mr Cameron and George Osborne "two arrogant posh boys", but privately some Tory colleagues agree.

The image has been reinforced by the picture of Mr Cameron's lifestyle painted at the Leveson Inquiry into press standards, which has cast an unflattering light on his so-called "Chipping Norton set" in Oxfordshire – the last thing the Prime Minister wanted or expected when he set up the inquiry.

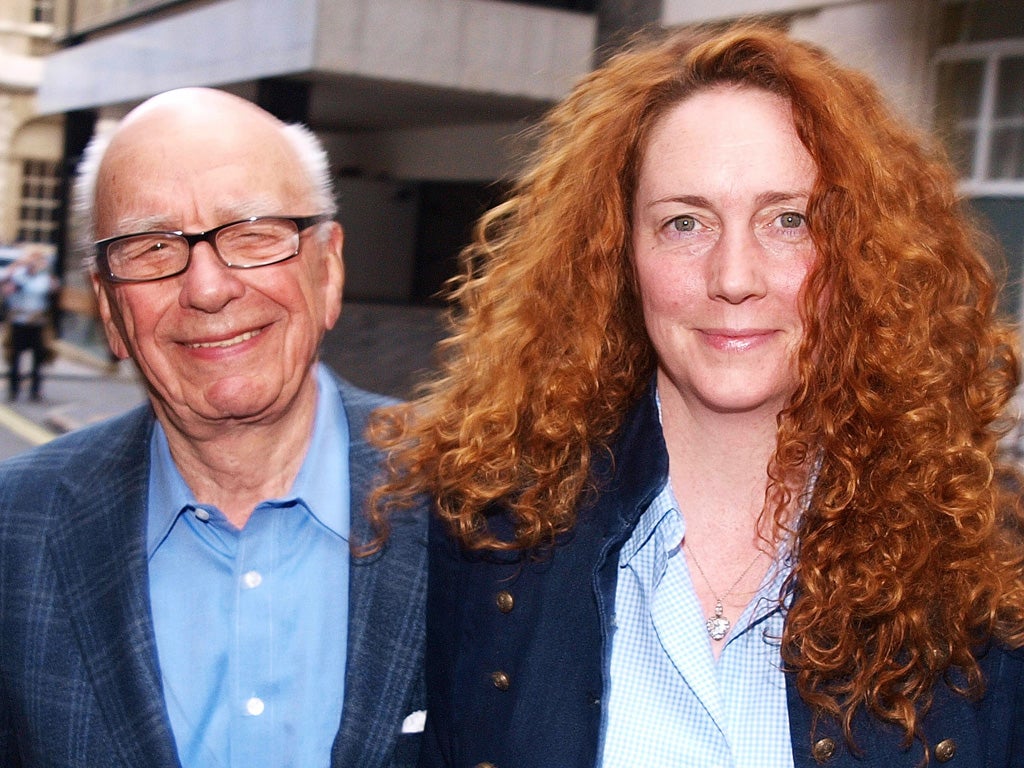

The abiding memory of Mr Cameron's five hours of evidence was that text message from News International's Rebekah Brooks about arranging a "country supper". Mr Cameron met up with his near neighbour and fellow horse-rider about every six weeks, he told Lord Justice Leveson.

The same Brooks text, highlighting her personal and the Murdoch empire's backing for Mr Cameron before the 2010 election, used the phrase "we're definitely all in it together". Ironically, the revelation makes redundant a slogan designed to show that the Coalition is implementing its spending cuts fairly. I don't think Mr Cameron or Mr Osborne will utter it anytime soon, as the Brooks version would soon be thrown at them.

Perhaps the signal all this sends to ordinary folk would not matter or last if we were living in good economic times. But the cuts and the return of recession make the gulf between the voters and the ruling political elite even wider. More importantly, the gap has been underlined by the Government's recent policy decisions.

Mr Cameron's advisers warned that cutting the 50p top rate of tax on incomes over £150,000 would run the risk of reinforcing the Tories' image as the "party of the rich". And yet he was persuaded to go ahead by Mr Osborne, who initially wanted to cut it to 40p, but compromised on 45p when Mr Cameron and Nick Clegg expressed doubts. Needless political pain.

Tory strategists cling to the hope that the voters are not following every twist and turn in the Leveson Inquiry. Tory polling suggests Ed Miliband is also seen as "out of touch"; some Tory MPs believe their party would be more vulnerable if Labour were led by Alan Johnson or Yvette Cooper.

But much damage has been done. When Labour attacks the Tories as "out of touch" in every statement, speech or soundbite, it no longer sounds like sour grapes, but a statement of the obvious. Labour doesn't need to relaunch the class war; the Tories are advertising their biggest weakness and Mr Cameron's Achilles heel. They are turning a caricature of themselves into what the public see.

As he pointed out in 2005, Mr Cameron could not choose his parents or his background. But he can choose his friends and, more importantly, his policies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments