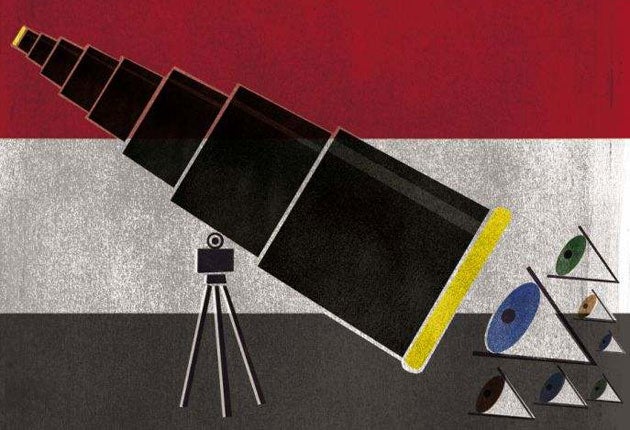

Adrian Hamilton: The one thing Chilcot won't reveal is the truth

Those who think the establishment a myth should look to the inquiry's membership

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What is the difference between the inquiry being led by Sir William Gage into the death in military custody of Baha Mousa and the inquiry chaired by Sir John Chilcot into the Iraq war? The simple answer is that Gage's inquiry into one terrible victim of the war will, according to Sir William, "follow the chain of command up as far as it leads," while the Chilcot inquiry into the whole circumstances of a war that split the country and led to the loss of hundreds of thousand of civilian lives in Iraq as well as irreparably damaging the international reputation of the country and its Prime Minister will not, according to Gordon Brown in setting it up, aim to "apportion blame."

Of course the two inquiries are not the same. Gage's is a "public inquiry" – as is the al-Sweady inquiry under Sir Thyne Forbes announced yesterday into the deaths of 20 Iraqis at the hands of British troops in 2004. They are led by judges with the full forensic duty to root out the truth as a matter of finding who did what, why and to whom. The Chilcot inquiry, in contrast, is a committee set up by No 10 to search documents and question witnesses – without evidence under oath or legal consequence – to learn lessons, and not to "determine guilt or innocence."

The last thing a government unable to avoid an inquiry once the troops had left Iraq wanted was a proper public one that would answer the hard questions on the legality and responsibility for this defining episode of the country's recent history. What it wants is a report that goes into endless detail, examines a great string of witnesses, gathers "a mountain range of documents" (in Sir John's words), uncovers some interesting material to keep the journalists happy and then ends up with a final report which says that, yes, there were lapses in the presentation of the case for war and there were serious deficiencies in the planning of the occupation (as we know from recently leaked government documents) but, no, there was no dishonesty in the intent, no lying to the House, no final illegality. Officials and ministers made mistakes but there was nothing dishonourable about the whole exercise or the individuals involved.

Much like the 1983 Franks report into the Falklands War, in fact. As the Foreign Secretary, David Miliband, said when first suggesting the inquiry, it would be modelled on the Franks Committee report, the "gold standard" as he put it of such investigations. Really? He seems to have forgotten, or never realised (Europe will never know how lucky they were that Miliband was not foisted upon them as High Representative), that the then Father of the House, James Callaghan, and almost every commentator dismissed the Franks report, which went into enormous detail and then ducked any broad conclusion, as a stitch-up.

"For 338 paragraphs," Callaghan declared, "he painted a splendid picture, delineated the light and the shade, and the glowing colours in it, and when Franks got to paragraph 339 he got fed up with the canvas he was painting, and chucked a bucket of whitewash over it". It was, as the commentator Hugo Young put it, "a classic establishment job. It studiously recoiled from drawing the large conclusions implicit in its detailed findings."

Quite so. Those who think the establishment a figment of the left-wing imagination, should look to the composition and terms of reference of this committee. When the "state" feels itself under pressure at its very centre, as it has during these disasters, it chooses carefully. Lord Hutton was chosen to investigate Dr David Kelly's death because, as a Northern Ireland judge who'd handled a succession of security cases, he could be relied on not to stray from his remit and undermine the government. As with Franks, he bemused the press with the amount of information and questioning on the record and then threw away the obvious conclusions.

So too with Lord Butler. A civil servant who'd held his 50th birthday party in his old school, Harrow, where he'd been head boy, he was never going to end his report into the use of intelligence with a conclusion that would undermine the system, whatever others might (and were even intended to) read into it. And thus it was.

Sir John Chilcot is no different. A Cambridge-educated civil servant with a background largely of dealing with the police and security at the Home and Northern Ireland offices and regarded as the softest questioner on the Butler committee isn't going to spit on his own background. Nor will Sir Roderic Lyne, Eton and the diplomatic service; or Baroness Prasher, who has become queen of the judicial quango network, or the two knighted historians, Sir Martin Gilbert and Professor Sir Lawrence Freedman. Not one of these figures is known to have voiced any public disquiet at the war. The two historians were both supporters of it.

The inquiry, said Sir John Chilcot, wanted only members "with experience of the workings of government from the inside". That rather gives the game away. It is the outsider who has always pursued truth most vigorously, particularly the judge trained to pursue lines of inquiry and catch out dissembling, as the Scott, Scarman and Macpherson reports all testify. What Sir John means is that he only wanted people who would share the assumptions of those questioned, as the ever so polite examination of officials in the first two days of hearings on Tuesday and Wednesday amply testified..

Sir John is also guilty of two other deceits (or "Blairisms" if that is too harsh a word). One is that the committee members are "completely independent" and come to the investigation from "different perspectives."

How you can say that when you do not have a single committee member who opposed the war, when there is neither an Iraqi nor anyone with experience of the Arabs nor is there anyone who understands the politics of it all beats me. Sir John tries to explain this away by saying that no one is from a party affiliation. But the whole point of the war was that the two main parties supported it. The Iraq invasion was not a party issue except with the Lib Dems.

The other 'Blairism' is the pretence that the report, when it eventually comes out next year or the year after, will "write the story of what happened through the whole nine years." And just how does he propose to do that when he has no access to the all-important US files or witnesses to the war nor the Iraqis who were the other side of the equation? This is the victor writing the history with a vengeance. For two historians of a reputation for document-digging but of pro-establishment leanings and little apparent sympathy for the Arab view or that of the anti-war critics, to lend their names to this charade demeans both themselves and their profession.

If you want to know why this should have been a public inquiry led by lawyers and under oath and not an exercise in driving a difficult issue into the political long grass you have only to look at the two public inquiries which are being undertaken into the Iraq occupation – those into the deaths of Baha Mousa, killed with over 90 injuries inflicted by his guards, and the 20 Iraqis killed in the so-called "battle of Danny Boy" in 2004.

War isn't just a continuum of diplomacy by other means, as the committee's questioning this week seemed to imply. It is the single most important act that a government can undertake, and one with the most terrible of consequences, on the perpetrators as well as the victims. Baha Mousa and his fellow Iraqis deserve a proper investigation of what was done to them. But then so does the country for what was done in our name but not with our assent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments