World's oldest Koran discovered in Birmingham: This will rejoice Muslim hearts

All we need now is a Dead Sea Scrolls-era Book of Job to surface in Newcastle or Nottingham

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In Islamic tradition, the “people of the book” (Ahl al-Kitab) consist of Muslims, Jews and Christians. As Islam spread into the Indian sub-continent, Hindus later came under the same broad umbrella.

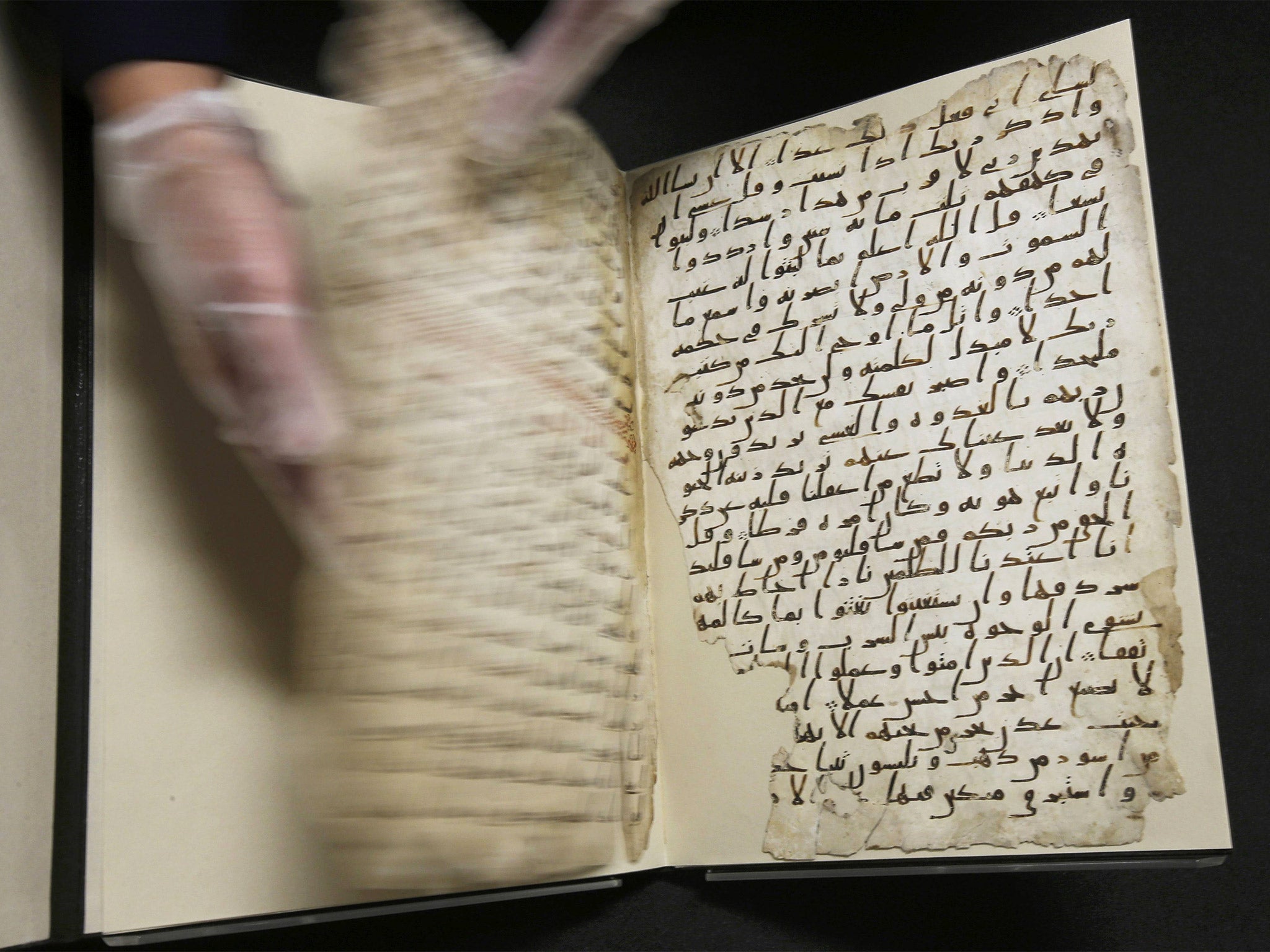

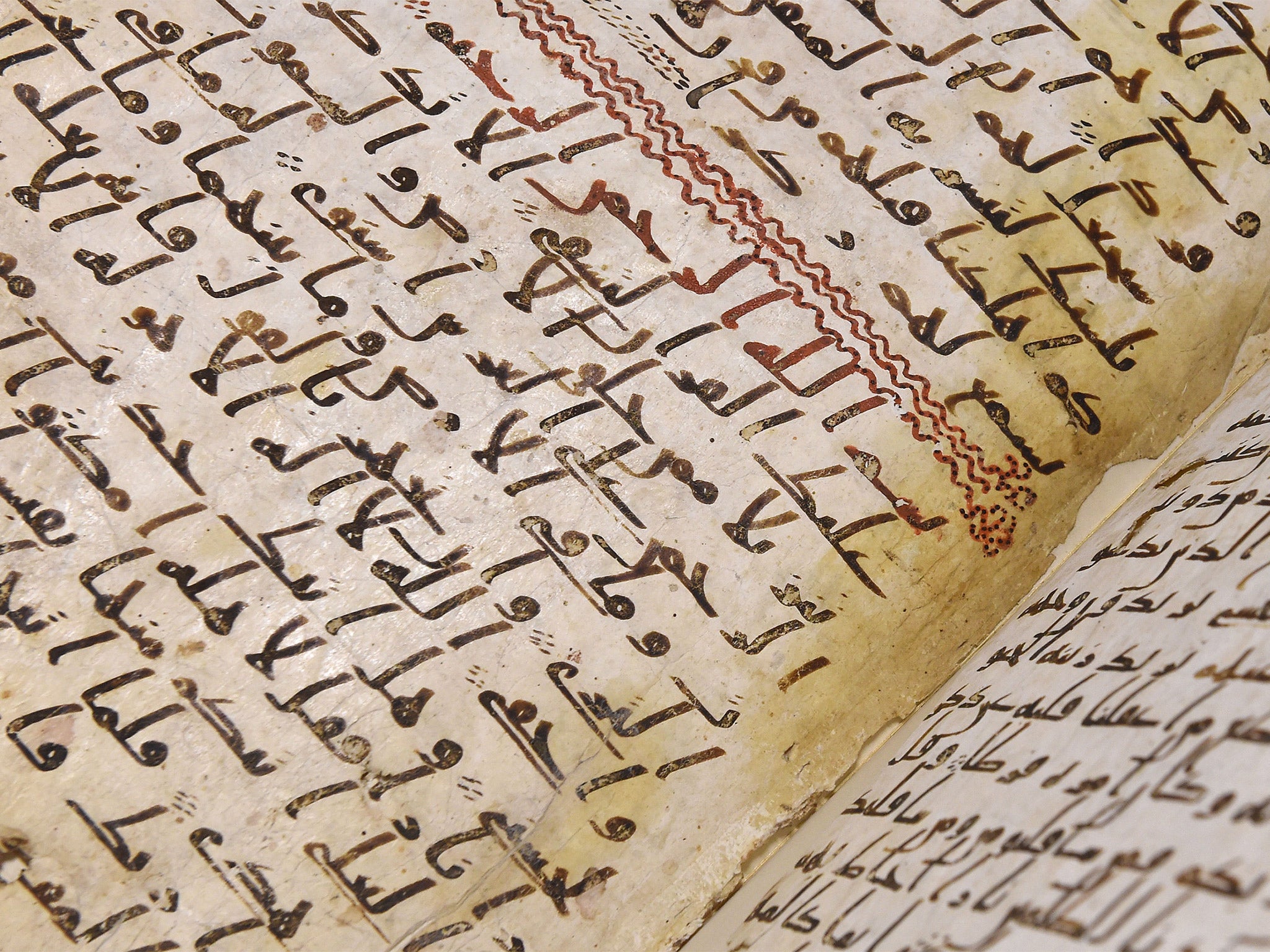

Even if they later say farewell to literal belief, anyone raised in a scripture-based religion is likely to harbour a lingering curiosity about the sacred written text. Atheists and fundamentalists alike remain people of the book. So the announcement that the University of Birmingham’s Mingana Collection contains what may be the oldest known fragment of a manuscript Koran has made media waves around the world.

Curiously, the radiocarbon-dating of these two parchment leaves to AD645 at the latest gives Birmingham a treasure to match a scriptural marvel further to the north. The John Rylands Library at Manchester University has, among its holdings of Greek papyri found in Egypt, an item identified as P52. By general consent, P52 is the oldest manuscript recognised to contain verses from the New Testament. Strangely enough, given the ferocious controversies that swirl around scripture, this fragment preserves the episode from St John’s gospel in which Pontius Pilate interrogates the captive Jesus and asks: “What is truth?”

“Earliest traces of monotheism located in Manchester and Birmingham”: it sounds like a spoof front-page, bomber-on-the-Moon style. But, supposing the leaves from the Mingana Collection withstand other verification, that would appear to be the case. All we need now is for a Dead Sea Scrolls-era copy of the Book of Job to surface in Newcastle or Nottingham. Then ecumenical pilgrimages would have to make large detours to the Midlands and the North.

For believers and doubters alike, the drive to return as close as possible to the sources of faith has motivated centuries of disputatious scholarship. In the case of Christianity, most reputable estimates date the four gospels between 65 and 100AD, with Mark the first and John the last. These composition dates make it unlikely that the Evangelists knew and heard Jesus. That fact has troubled Biblical literalists since critical scholarship began to investigate the background of the texts in the early 19th century. True, some of the epistles of St Paul – such as the first letter to the Thessalonians – may come from the early-50sAD, closer to the accepted years of Jesus’s ministry. But the absence of first-hand, near-contemporary witnesses for the life of Christ has often bothered the kind of “people of the book” who need or seek a documentary crutch for faith.

In contrast, Islamic tradition has often claimed that its scripture – as disclosed to the Prophet Mohamed in a sequence of revelations by the archangel Gabriel – lacks the textual confusions of its Abrahamic cousins. For Tarif Khalidi, one of the Koran’s modern translators, “the result is that Islam has possessed a definitive sacred text from a very early point in its history. There are simply no ‘apocrypha’ where the Koran is concerned.” More liberal schools of thought about the Koranic text did in fact flourish, as far back as the ninth- and 10th-century Baghdad of the Abbasid Caliphs. Indeed, as a recent issue of the journal Critical Muslim amply demonstrated, Islam had its internal “free-thinkers” – accepted and even honoured – long before Christianity.

Modern fundamentalism has tried to bury that open-minded past. Yet the Koran has not escaped the kind of scientific criticism that shook literalist Christianity in the 19th century, and continues to worry Bible-believers today. Academic debates around the origins of Islam in seventh-century Mecca, in particular the relation of its first followers to their Jewish, Christian and pagan neighbours, briefly swept into the mainstream thanks to historian Tom Holland.

In 2012, Holland published his revisionist book In the Shadow of the Sword, and made a documentary for Channel 4 entitled Islam: the Untold Story. Holland drew on other researchers, such as Fred Donner, of the University of Chicago, whose work on the Arab-Jewish-Christian crucible in which Mohamed lived have not attracted serious dissent. Holland, however, found himself subject to charges of “Islamophobia”. His core argument, voiced in an interview, is: “All three religions… emerged out of the same melting pot – and yet all three have constructed backstories that aim to occlude the fact.”

Authentic “Islamophobes” – usually Christian fundamentalist propagandists – do care deeply about the date of the Koran. They tend to seize on any evidence of the composition of the canonical text later than the time of the third Caliph Uthman (who died in 656AD) as, well, manna from sectarian heaven. In this light, the radiocarbon-dating of the Mingana fragment will certainly bring comfort to traditionalists. For David Thomas, Birmingham University’s professor of Christianity and Islam, “The person who actually wrote it could well have known the Prophet Mohamed… and that really is quite a thought to conjure with.” Muhammad Isa Waley, senior curator at the British Library, calls the dating “news to rejoice Muslim hearts”, a verdict surely coloured by scholarly quarrels of the past few years.

Yet we would not be able to study these precious leaves, or 3,000 other Middle Eastern manuscripts, had Edward Cadbury not funded three research trips by the Chaldean priest Alphonse Mingana in the 1920s. Like most of his Birmingham chocolate-manufacturing dynasty, Cadbury was a Quaker, part of a spiritual community for whom dogma, dates and disputes matter infinitely less than the inner light of truth and conscience. So this latest, fascinating chapter in the history of monotheist scripture comes to us courtesy of a patron whose own code of faith denies the unique authority of scripture. If and when the Mingana carbon-dating begins to stir dissent, we should bear that in mind.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments