Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last night I attended a winter wedding in Karachi, Pakistan. There was singing and dancing and both men and women mingled together under a voluminous violet tent with strings of marigolds hanging down the poles. The men wore shalwar kurta with waistcoats and warm woollen shawls. The women wore brightly-colored shalwar kameezes, saris, and ghararas (long skirts), moving around the tent like glittering butterflies as Bollywood music thumped from the speakers around the dancefloor. Some members of the family had their heads covered in jewel-toned scarves that matched the colors of their clothes. One or two of the women wore their traditional dupattas easily over their heads. The majority of the women, though, wore their hair free, blow-dried into elaborate curls or straight curtains of silky dark tresses.

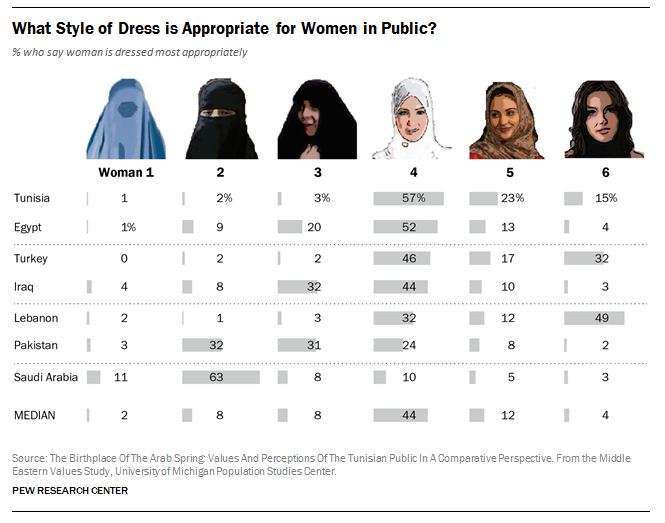

This is the Muslim country in which I was born and raised, and the scene refutes the results of the recent University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research survey asking “What style of dress is appropriate for women in public?” The participants were given six headshots of brown women wearing various types of headgear, from most to least covered. Which is ridiculous, because everyone knows that at a Pakistani wedding the focus is on your clothes, shoes, jewelry and handbag. Nobody’s looking at your head unless you’ve actually decided to go punk and shave all your hair off.

The study found that few favored the type of burqa known colloquially as the “shuttlecock”, the blue bag with mesh over the eyes favored by the fashion-forward Taliban in Afghanistan. The slightly more liberated black burqa with matching face-veil garnered more support from their chic peers in Saudi Arabia. Most popular in this survey seemed to be a blood-circulation-cutting white hijab over a woman’s head, and only Lebanon favors godless women who don’t want to cover their hair at all (no surprise there, as Lebanon is considered as un-Islamic as you can get while still being Muslim).

But while the researchers thought that they were perhaps uncovering a profound truth about Muslim opinion on women’s fashion, the survey provoked a degree of ridicule amongst Muslims on social media. What purpose did asking the question serve beyond a strange Orientalist obsession with what Muslim women wear? Who was answering it, men or women? And why should it matter so much what “people” think women “should” wear – can’t Muslim women decide for themselves what is appropriate without input from an anonymous group of participants from “around the world” (in truth seven Middle Eastern Muslim countries, as if Muslims don’t live anywhere else, like Europe, America, or Africa)?

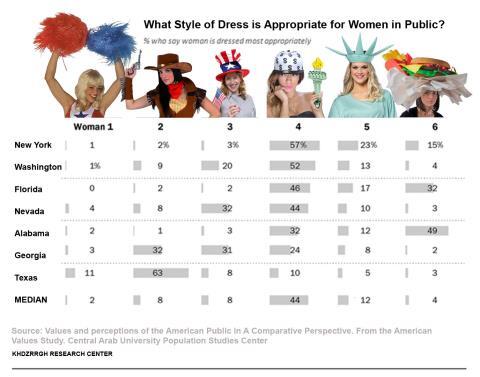

The best response to it was blogger and satirist Karl Sharro’s parody survey by an Arab university asking “What style of dress is appropriate for American women?” Six women were presented wearing these styles of headdress:

If I were writing about this survey, I would ask, in a breathless headline worthy of the Daily Mail, “So, just why ARE people so obsessed with how Muslim women dress?” In the wedding I described above, nobody thought twice about what anyone had chosen to wear; even the young girl with the scandalously low-slung sari and the tight body sheathe sequinned top that revealed her midriff and bare shoulders flitted around at ease in the gathering -- the shameless hussy.

Growing up in Pakistan, I’d never seen anyone wear a hijab, and burqas were reserved for the very traditional women of my family who observed “purdah”, the separation of men and women first prescribed for the wives of the Prophet Mohammed and adopted by the female descendents of his family. It was only in the late 1980s that I saw my first hijab, worn by the mother of a Pakistani-American girl from Peoria, Illinois. Even the draconian years of Zia ul Haq’s Islamic dictatorship couldn’t make Pakistani women abandon their bouffant hairstyles and traffic-stopping golden “streaks”.

Saudi-Wahabi social influence filtered to Pakistan and much of the rest of the non-Arab world throughout the next two decades, thanks to a campaign that attempted to export the kingdom’s religio-social values to its would-be satellite states. Slowly, more and more women started to wear the black burqa and the tight hijab – not because they wanted to be pious, but because they wanted to emulate what suddenly seemed trendy amongst Gulf Arabs. The Iranian-style manteau and black scarf never caught on in Pakistan because being able to carry off the look requires the type of bold beauty that is the signature of Iranian women, while we Pakistanis prefer to rely on an amalgam of Bollywood, Gulf Arab, and our own indigenous traditions to make our fashion statements.

Which brings me to my point: Muslim women’s fashions have been interpreted and overanalyzed by the Western world as some sort of profound assertion of political identity or religious stance. Yes, there is an element of that in there, but the bigger truth is that Muslim women wear what they do, including what’s on their heads, because of how it makes them look and feel, just like all women around the world, and it takes on the cultural overtones of the milieu in which they live. There’s no need to survey this or pathologize it: there’s certainly no point in turning it into a value judgment. If people truly care about the autonomy and agency of Muslim women, as this survey seems to imply, they should just leave the warddrobe choices to Muslim women themeselves, and find a better medium through which to express their concern.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments