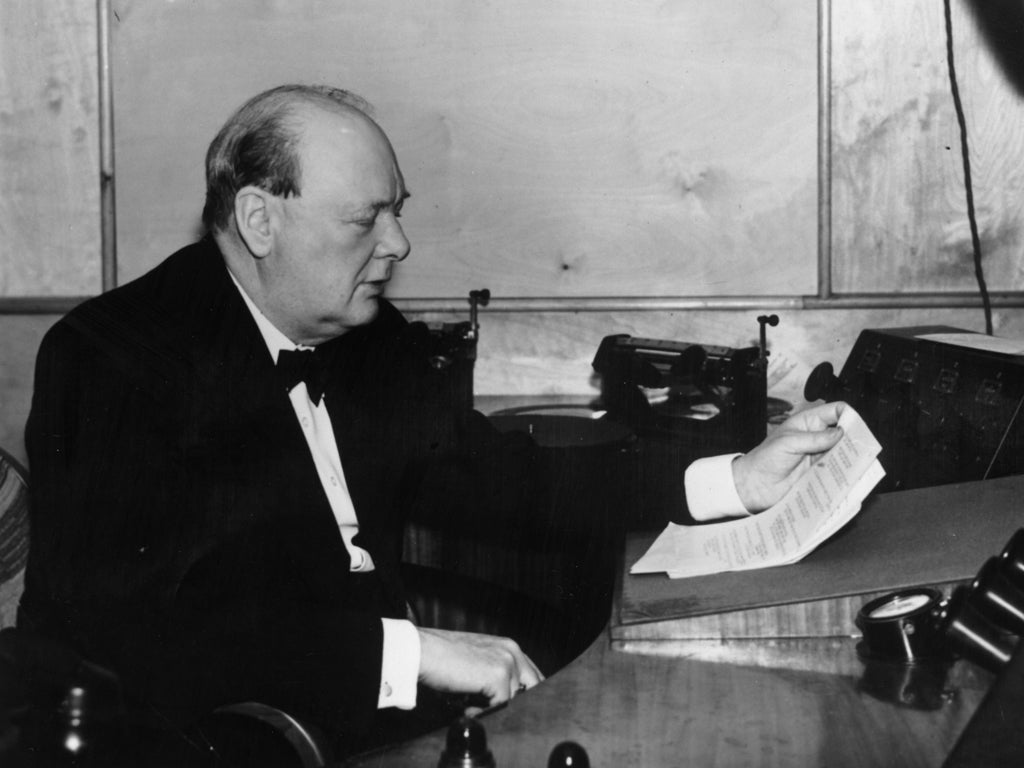

Why don’t more politicians wax poetical like Winston Churchill?

There are one or two who would probably contribute to the public good much more effectively by writing poetry

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A poem was published for the first time this week, and had wide, curious coverage.

If that sounds unusual, it’s probably because it wasn’t by a poet, and wasn’t by anyone alive. Winston Churchill was a talented and able writer with a notable relish for words. Still, surprisingly, there are not many known poems by him – there is one entitled “Influenza” from his schooldays and a few impromptu back-of-a-postcard compositions: “Only one thing lacks these banks of green—/The Pussy Cat who is their Queen...”

The poem just unearthed, entitled “Our Modern Watchwords”, is a little more substantial. Written in 1899 or 1900, it shows the strong influence of Kipling’s famous “Recessional” of 1897, but has some distinct touches of its own: “The silence of a mighty fleet/Portends the tumult yet to be./The tables of the evening meal/Are spread amid the great machines.”

It’s interesting to see a military and political figure not only writing poetry, but writing poetry in a vein influenced by very current poetic style. Trying to think of an equivalent today is challenging. It isn’t that poetry has gone away. In fact, people reach, more than ever, for poetry at elevated moments of their lives, and it is not uncommon for them to write heartfelt rhymes to read out at memorial services or even weddings. What would be very unusual would be to write a poem in the style a famous poet was using two or three years ago, as Churchill did.

There are many charming personal poems preserved on the internet, written for people’s boyfriends: certainly cherished by the recipients, but not ones that have needed much influence from poetry written in the past 100 years. One amateur bard writes: “I smile when you hold me./And as you kiss my virgin lips,/My heart, it seems to flutter./And when you hold my hand so terribly shaky are my hips.” Poetry, as a professional endeavour, seems to have grown remote from what people want to achieve with it. If a politician or a serving officer, these days, wrote a poem, as they are quite likely to, it would be truly astonishing to see them writing in the style of George Szirtes.

This is a shame, because, in fact, poetry these days is often entertaining and accessible. The separation between ordinary people, and even many of the professional classes, and poetry must be regretted. This is not the case in many foreign cultures. There is a saying about Bengalis: “One Bengali, a poet: two Bengalis, a film society: three Bengalis, a political party.” That is certainly true from my experience. Half my Bengali in-laws are bankers, lawyers or university professors, but also write poetry, either for their own private pleasure, or for publication, and see nothing so very remarkable in it.

Elsewhere, the Tunisian opposition leader Chokri Belaid, assassinated this week, was a well-respected poet. In America, too, there is a place for poetry in public life that goes beyond our own laureate in prominence. The quality of the poetry produced on public occasions in America might, you would have thought, have acted as encouragement to the professional classes. Richard Blanco’s inaugural poem for President Obama this January was quite a reasonable effort. But surely quite a lot of lawmakers, listening to Maya Angelou’s poem for President Clinton’s first inauguration must have thought, not without justice, “I could do that”: “Lift up your hearts/Each new hour holds new chances/For new beginnings.”

Surely there are politicians today who are up to that undemanding level. I can’t help thinking, either, that among the 650 members of the Commons and 760 of the Lords, there would be one or two who would contribute to the public good much more effectively by writing poetry, even poetry as rudimentary as Ms Angelou’s, than by going around pontificating on global crises and the important lessons to be learnt after one crisis or another. After all, it wouldn’t be necessary, like Churchill, to attempt to imitate anything challenging, like Kipling.

Horse lasagne just needs a good ad campaign

A great deal of panic is being fomented by the discovery that Findus “beef” lasagne was, in fact, made up of anything up to 100 per cent horse meat. Nobody can show that anyone was harmed in any way by eating the horse meat. I’ve given it a great deal of thought, and have come to the conclusion that I personally would be a great deal likelier to eat ready-made Findus lasagne if it had been announced as being made out of horse in the first place. Out of curiosity, you understand.

Back when I was a student, the late-night streets of Oxford were paved with villainous vans selling what were known as Deathburgers. The most celebrated was one with The House of Fritzi painted on the side, staffed by a foul-tempered transvestite. Our assumption that the Deathburgers were more likely to be horse than cow was only interrupted by the belief that some vans operated directly out of the John Radcliffe hospital morgue. Still, nobody died from eating one – or hardly anyone, I dare say.

Since then I’ve eaten any number of things that would make front-page news if they were found in Findus lasagne. Last week, it was a woodcock, a bird whose bowels may be eaten, since the bird defecates forcefully on take-off. Once in Vicenza, I didn’t recognise a word on a menu: “Pony,” the waitress said, encouragingly. Even here, you can easily buy sausages openly made out of donkey in Clapham, and very good they are, too. All in all, the problem with Findus’s lasagne di cavallo could have been overcome with honest labelling, and a really well-constructed PR campaign.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments