Why are we so obsessed with therapy?

What is of value tends to be lost or perverted if we turn all that is therapeutic into therapy.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Not so long ago, therapy was widely seen as something only for the seriously disturbed or neurotic, overeducated Americans.

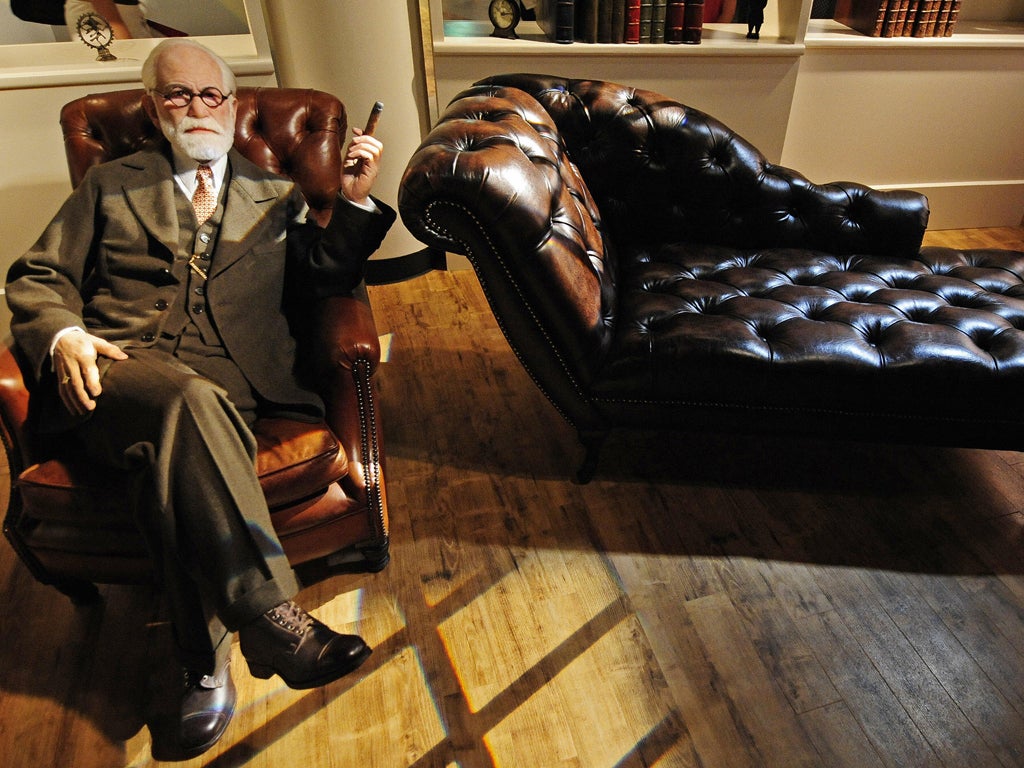

Now, all that is good is being turned into therapy. Rather than seeking help on Dr Freud’s couch, people are turning to Monty Don’s allotment or Jamie Oliver’s kitchen to soothe their troubled psyches.

Ancient philosophy is also undergoing this process of therapisation. Today is day six of “Live Like a Stoic Week”, an experiment led by a group of academics and psychotherapists as part of an ongoing project to “examine the implications of ancient healthcare and philosophy for our own society”.

At its best, this trend marks a recognition that many of the personal struggles we face are not “psychological problems” of a more or less medical kind, but part and parcel of the confusing and often difficult search for meaning, value and purpose. Gardens, kitchens, literature, philosophy and art can all help in this quest. However, what is of value in them threatens to be lost or perverted if we turn all that is therapeutic into forms of therapy.

For example, it does seem to be true that, on the whole, people benefit from having some engagement with the outdoors, and for some, spending time in the countryside is a better “treatment” for depression than pills or talking cures. But that does not mean there is something called “nature deficit disorder” for which the prescription is “ecotherapy”. Contact with nature is not like vitamin D: something we need a minimum dose of, or else we stop functioning. It is simply something that most – but importantly not all – find an important part of a good, rounded life.

There are lots of things that fulfil such roles, but it would be absurd to think of their absence as disorders and their introduction as treatments. Most people would rather have a good, intimate relationship than not. But that does not mean the single suffer from “partner deficit disorder”, the cure for which is marriage.

The things we value tend to make us feel better, but that is not primarily why we value them. If you love your partner, for example, she will almost certainly make your life happier. But the reason you will stick together through hard times is that the relationship with her is valued more than how being in it happens to make you feel.

Philosophy is an even clearer example. The only good reason to embrace a philosophical position is that you are convinced it is true or at least makes sense of the world better than the alternatives. I’m not a stoic because I do not agree that we are all fragments of an all-pervading divine rationality which is providentially organising the world, or that Epictetus was right to say you should not be disturbed if your wife or child dies or that “my father is nothing to me, only the good”. To become a stoic is to endorse the truthfulness of its world view and accept its prescription for how you ought to live, not just to like how it makes you feel.

Aaron Beck, the founder of cognitive-behaviour therapy, and Albert Ellis, founder of rational-emotive behaviour therapy, both appropriated Stoic ideas for their own ends, as does the philosopher Richard Sorabji, who says of Stoicism: “I choose the bits which I find helpful and I don’t take the full theory.” Such cherry-picking is perfectly legitimate. What’s objectionable is praising the joys of scrumping as though it were on a par with the care, dedication and understanding of growing an orchard.

In muddying the waters between philosophies of life and therapy, people do therapy a disservice, too. Therapy is often criticised for merely providing crutches, tools and strategies for coping, not treating the whole person. But at its best, that is all that therapy can and should do. Developing a comprehensive outlook on life, along with a set of values that guide us, is far too important a matter to be left to therapists. The therapist’s job is to help clients get back to the position of being able to pursue their own quests through life, not deliver them to their destinations.

The most misguided aspect of Stoic week, however, is the collection of “data”, in the form of well-being questionnaires taken by self-selecting participants before and after. Not only is this a badly designed experiment which will prove exactly nothing, it just is not how a philosophically based “way of life” should be assessed. It would be as stupid to become a Stoic because tests showed it tended to make people happier than Aristotelianism as it would to choose your religion, or lack of it, on the basis of which one tended to make people feel better. Latter-day Stoics should not seek to vindicate their approaches through “evidence-based” measures of output. The idea that all that is good can be measured should be rejected, not embraced, by advocates of finding meaning through engagement with things of value in the world.

Stoic week has a valuable part to play in getting people to think more about how the deepest issues in their lives might not be just local psychological difficulties but concern more profound questions about how to live. But please, let’s not reduce all that’s true, good and beautiful to techniques and interventions to cure the blues and put smiles on our faces. Seek first what is true and of value, and then whatever happiness follows will be of the appropriate quantity and, more importantly, quality.

Julian Baggini is the co-author of ‘The Shrink and the Sage’

Twitter:@microphilosophy

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments