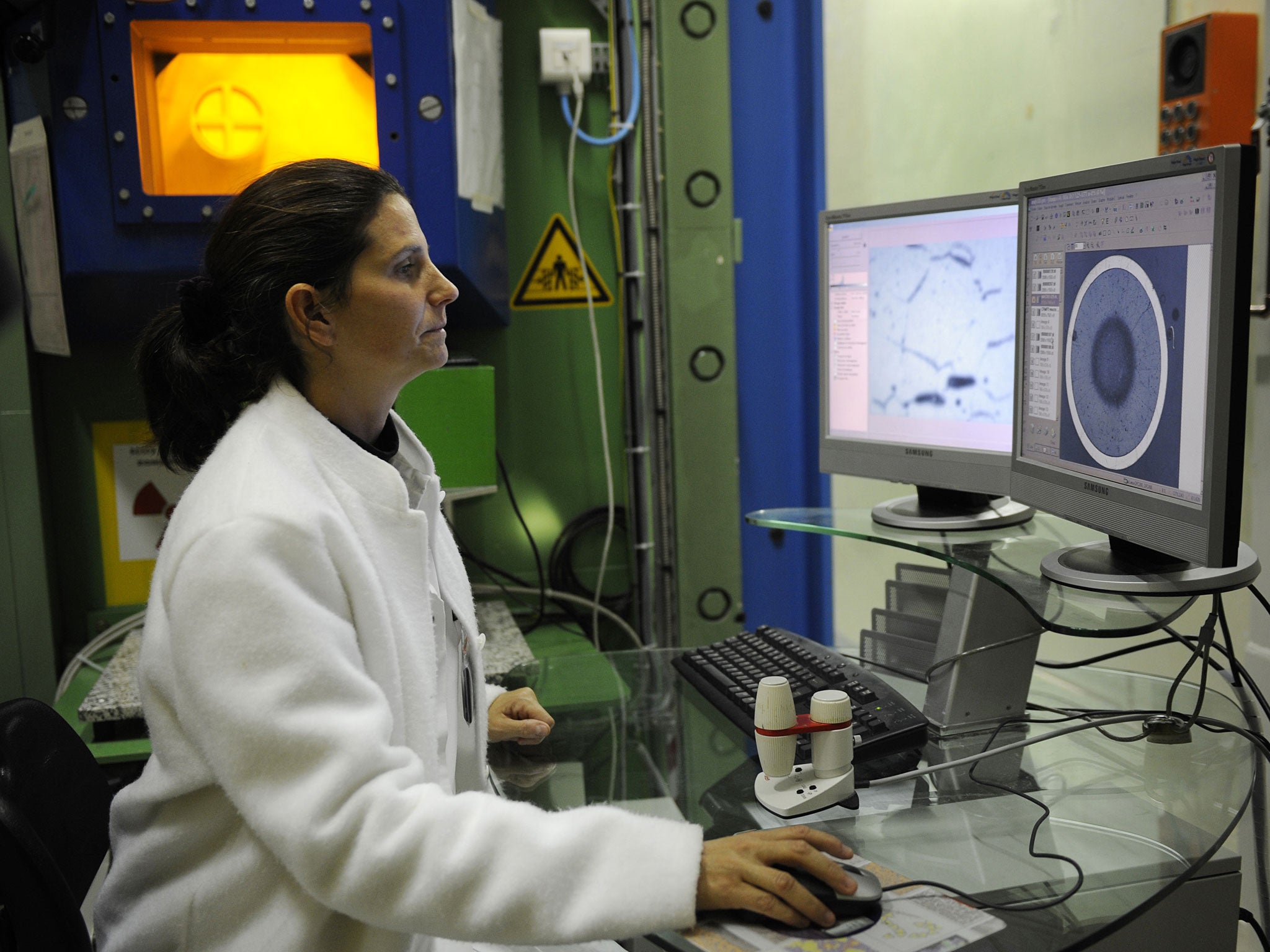

Where are all the female engineers?

Almost as many girls as boys now take GCSE physics but at A-level nearly half of all classes are 100 per cent male

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain has the lowest percentage of female engineers in Europe: a truly shocking 8.5 per cent. In Sweden, that figure is 25 per cent, in Italy, France and Norway, it’s 20 per cent. Still not good enough, but on the right track.

Last week, Crossrail – Europe’s largest engineering project – hosted Engineer Your Future, a programme designed to promote engineering as a career for girls. Crossrail pointed out that with mammoth projects like HS2 and Thames Tideway underway, there is a chronic shortage of engineers.

Britain needs to double the number of engineering graduates to 87,000 a year to meet future demand. However, half of all state schools do not currently send a single girl on to university to study maths or sciences. Crossrail itself has worked with more than 100 schools to try to do something about this gaping skills shortage.

I was digesting this while at the snappily-named CH2MHILL engineering company, which works with my daughter’s school – among others – to give pupils direct hands-on experience of what engineering actually entails.

I sat, with other proud parents, in their presentation suite as my daughter and her friends presented - via powerpoint and CAD programmes – the results of their six-months’ work on preparing better flood defences in north London.

I understood possibly a third of what they were talking about - unsurprising given that I didn’t take Maths or Physics A-Levels. But I could understand the palpable attention to detail, creativity, and sheer brain power displayed by both the students and their talented CH2MHILL mentors alike.

A magnificent Italian civil engineer then addressed the room, telling us her story of coming from Italy to England to make good. Inspiring stuff, And then, a senior male engineer told us a story about some of the sexism in the industry that women encounter and overcome.

How many times have we heard this same sorry tale? I remember lunch in the BAE boardroom years ago talking about exactly this issue. What happens to all those clever young girls? Where does the education system fail them – or is it the home? Is it parents not seeing engineering as aspirational for girls? Both of the above?

Almost as many girls as boys now take GCSE physics but at A-level nearly half of all classes are 100 per cent male. The figure is slightly better at girls-only schools. Is it peer pressure? Are girls being put off by the idea that engineering means getting yours hands dirty and “unfeminine” rather than about using brain power?

That’s at least partly the view of Dame Ann Dowling, the head of the engineering faculty at Cambridge University, who - by the way - helped design both a single-winged airplane and low emission jets. Dame Ann famously once suggested that parents buy their daughters Lego, but more seriously suggests that society needs to emphasise that engineering is a people business that relies above all on team communication.

The earnest Spanish male and sparkling Irish female engineers who were my daughter’s mentors needed no such further exhortation. Britain is the land of opportunity in Europe, they said. There is almost no work for engineers in Spain, next to nothing in Ireland. If they can see it, why can’t we? And, specifically, how do we stop this lack of female engineers story remaining “an old chestnut”?

Stefano Hatfield is editor-in-chief of High50

Twitter: @stefanohat

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments