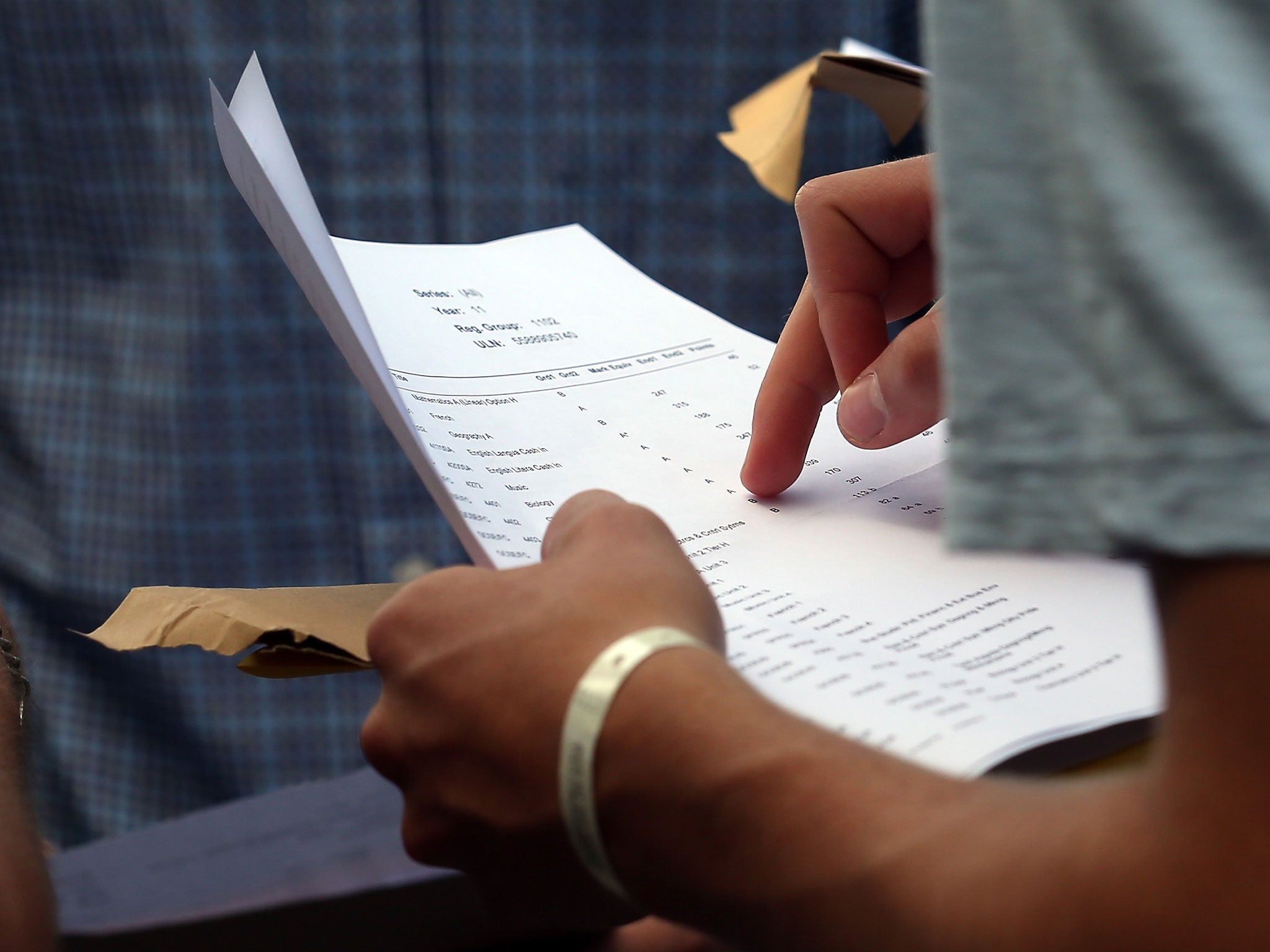

What's more important: skills or grades?

Even if they get the results they want, students have been warned that they might still lack what employers are really looking for

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is a cruel joke doing the rounds on the internet, poking fun at the editor of a certain newspaper.

It invites applicants who can jump the highest to get in touch with him, pronto, ready for his paper’s coverage of the A-level results (he’s partial to adorning his newspaper with pictures of photogenic boys and girls leaping for joy at their five A stars).

It’s that time of year again when newspapers and the airwaves are filled with tales of exam successes. This week, it’s A level derring-do; next week, GCSEs.

This year, universities are falling over themselves to attract students. Around 500,000 places are available – a record. With the tightening of A-level marks, so that resits and early A levels in January have been scrapped (both used heavily by the more savvy schools to bring up their results), more pupils than ever will miss their grades. The competition among the universities will be intense.

Surely, though, we’ve gone too far. Of those half a million degrees, how many are actually worth the paper they’re written on? More to the point, how many justify the cost, how many hold out false hope of some automatic entry to a stellar career?

That’s not to knock the sense of personal achievement. There is nothing more uplifting than attending a degree ceremony and seeing the pride on the faces of relatives for whom university was always a pipe-dream.

But as the totals of graduates have grown, as the universities have increased in size and number, as “uni” has entered the mainstream, so too have the complaints of employers become more voluble.

It’s as if we’ve been so busy attempting to reach Tony Blair’s magic target of 50 per cent of sixth-formers attending university that we’ve failed to keep an eye on the end game.

Amid the euphoria yesterday, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) released a statement. Towards the end, after the offering of congratulations to those who worked hard, applauding the rises in science, maths and computing, and the bemoaning of a drop in language students (“Europe remains our largest export market so to see yet another fall in the languages used on our very doorstep is a blow”), was a comment on more students going to university.

“University is a passport to success for many young people – and graduates are in high demand by employers. But there are other equally successful routes to a great career – including high quality apprenticeships - and we know that ‘earn while you learn’ options, which provide top-quality training and avoid tuition fees, are increasingly attractive. It’s not just universities competing hard for young talent, but businesses too.

“We need to ensure that all young people have the information they need to make informed choices about the right path for them.”

Continued the Eeyores at the employers’ organisation: “We need to reform Ofsted so that schools focus on not just academic progress but on the development of young people’s character, resilience and willingness to go the extra mile. There is a disconnect between too many young people’s perceptions of work and the reality.”

Coming from the CBI that is pointed stuff. The clear implication is that we’re producing too many people who hold useless degrees, who would be better off if they’d taken vocational apprenticeships. What’s more they’re too precious, too lazy, want everything on a plate, and are not prepared to put the hours in.

That is the experience of many of the large employers I talk to. They’re increasingly dismayed at the quality of school and university leavers applying for jobs. Rote learning has not equipped them to self-start, to solve problems on their own. It’s more than that, however: this generation wants it now. Having been pumped up by their schools, parents, universities, media, they think they’re somehow entitled.

It’s five years since Sir Terry Leahy, then the boss of Tesco, highlighted the problem: “Sadly, despite all the money that has been spent, standards are still woefully low in too many schools. Employers like us… are often left to pick up the pieces.”

He was followed a year later by Lucy Neville-Rolfe, Tesco’s then director of corporate and legal affairs, who said school leavers had basic problems with literacy and numeracy, and have major “attitude problems.”

Then, a year after that, in 2011, the Young Enterprise charity commissioned a survey which found that three in four corporate chiefs believed graduate skills were poor. One respondent, when asked to identify the skills that were lacking, said “too many to list”. They then went on to list some of them: “Commercial awareness, written and spoken English to a high enough level, technical skills, interpersonal skills, you name it.”

Ian Smith, the charity’s chairman, said that many firms were forced to hire foreign workers as a result, and he added: “The situation is getting worse because the Department for Education is adopting an alarmingly narrow focus on academic skills and exams. This will make it less likely that students emerge from education with these employability skills.”

Roll forward to 2014 and the CBI is still bemoaning the same weaknesses. And not only the CBI. The British Chambers of Commerce also said yesterday, again after lauding this year’s crop: “Despite strong academic results, youth unemployment remains persistently high, and action must be taken to ensure young people are attractive candidates to employers looking to hire. Young people should leave the education system with a career direction that is relevant to them and the skills and attitude that employers want.”

Five years, and judging by the employers’ comments, there is still not enough progress. If the Government was a pupil, based on its work to date, there would only be one outcome: “Fail.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments