What a tragedy that we couldn't stop the war in Iraq despite marching in our thousands

Forget the expenses scandal: it was Iraq that exploded what trust millions had in our political establishment. But the real anguish lies elsewhere.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

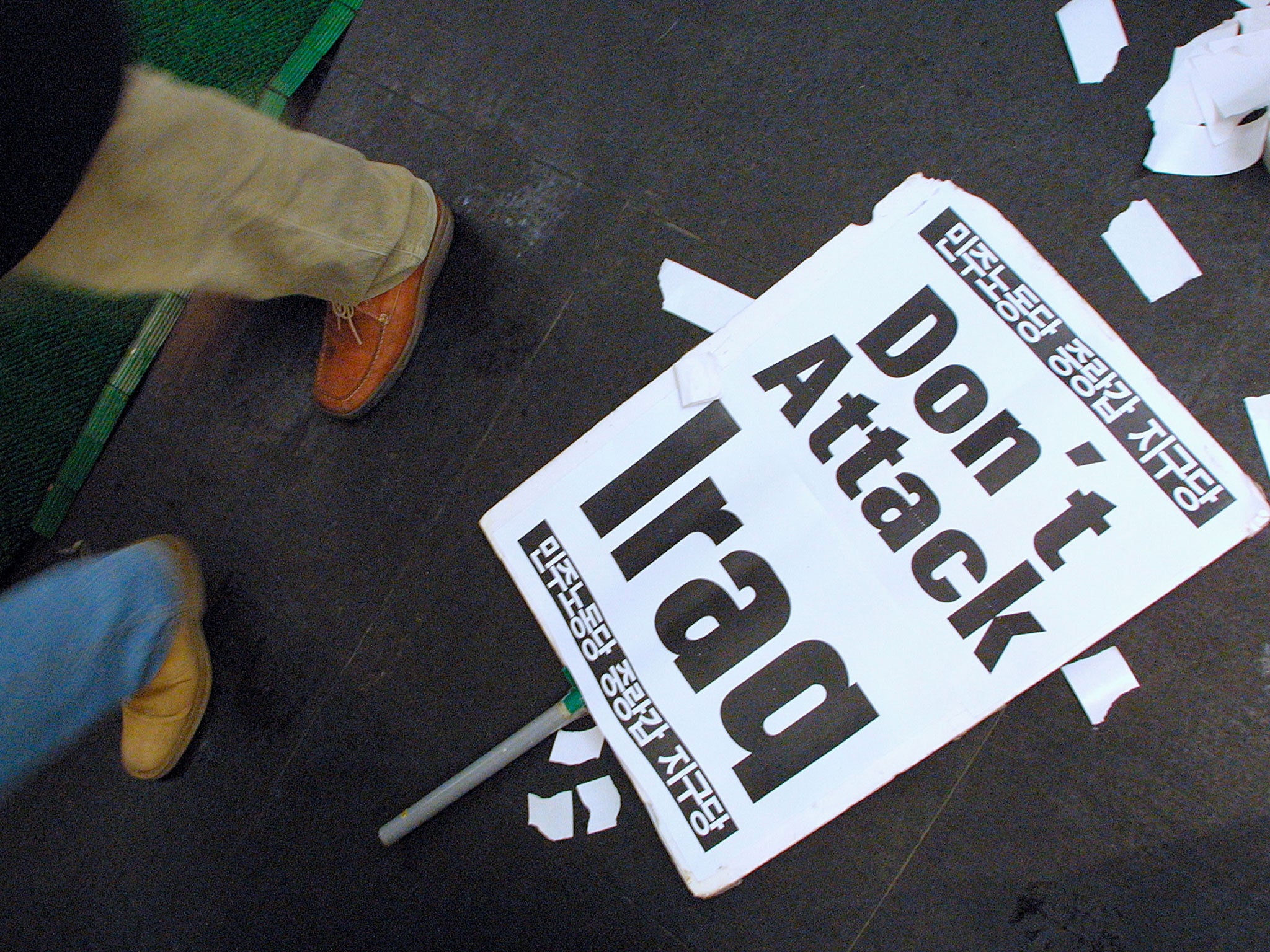

Your support makes all the difference.Almost exactly a decade ago, on a bitingly cold February day, we marched in our hundreds of thousands to stop a catastrophe. The historic demonstration against the Iraq war was more of a shuffle than a march: the streets were too crammed to walk very fast. The coach to London was packed full of car workers. Lollipop ladies, firefighters, supermarket shelf stackers, lecturers, shopkeepers marched: there was a euphoria that people power brings. When we left for our pick-up points, placards scattering the street, chants still echoing in the evening air, we thought we had won. How could the greatest mass of demonstrators to have ever swarmed through Britain’s streets be tossed aside?

It is a memory now punctured with bitterness. Yes, we helped trigger one of the greatest parliamentary rebellions in history as 139 Labour MPs defied the Whip, but the largely united Tories came to Tony Blair’s rescue. When I visit schools, students who were six, seven or eight years old when we marched ask how they can change anything if up to two million demonstrators couldn’t. And forget the expenses scandal: it was Iraq that exploded what trust millions had in our political establishment. But the real anguish lies elsewhere. The consequences of the Iraq obscenity were far worse than those of us who yelled “Not In Our Name” imagined. Years of blood and chaos followed. There can be no sense of triumphalism or vindication.

We were right about the false pretext: the non-existent weapons of mass destruction. It wasn’t a based on a hunch. We listened to Scott Ritter, the Republican-supporting former UN chief weapons’ inspector, who declared months before the first bombs fell that “since 1998 Iraq has been fundamentally disarmed”. We understood that the former foreign secretary Robin Cook knew what he was talking about when – in his historic resignation speech – he declared that “Iraq probably has no weapons of mass destruction in the commonly understood sense of the term”.

We refused to accept all the desperate contortions used to wrap the invasion in pseudo-legalese. It was illegal,” said the UN Secretary General Kofi Annan in the aftermath; it was “contrary to international law”, Sir Michael Wood, former chief legal adviser to the Foreign Office, told the Chilcot inquiry.

Neither did we believe it was motivated by humanitarian considerations, not least given the West’s appalling record of supporting brutal dictatorships. It is a scandal which continues today, from Saudi Arabia to Kazakhstan – whose dictator is currently employing Tony Blair to the tune of $13m a year. The CIA originally helped the Baathists into power: they even supplied lists of Communists who were promptly slaughtered. The West armed and supported Saddam in his war with Iran, and when anti-war Labour MP Jeremy Corbyn stood up in Parliament in 1988 to denounce Britain’s support for the Baathist tyranny after the gassing of the Kurds, he was a lone voice. Nearly all of those who used the suffering of the Kurdish people 15 years later to justify the invasion said nothing.

At a talk when I was at university, one of Britain’s most senior military figures predicted that 99 per cent of Iraqis would greet the occupiers with flowers; the other one per cent would initially hold back out of fear of Baathist reprisals. Hubris does not even cover it. A Sunni uprising began almost immediately; rebellions among the majority Shia population would follow. Iraq became a playground for al-Qa’ida-inspired fanatics who previously had nothing to do with the country. More than 12,000 civilians were murdered in more than a thousand suicide bombings in the first seven years alone. A grotesque sectarian bloodbath ensued: decapitations, car bombs, mass graves, bloated bodies floating in rivers.

Debating how high a pile of bodies reaches is a grubby business, and statistics have a habit of stripping humanity out of an argument. But the human cost matters. The occupiers refused to count the dead, leaving it to wildly differing estimates. The Iraq Body Count’s conservative figures are at least 172,906 violent deaths; the Iraqi government and the World Health Organisation estimated up to 223,000 killed in the first three years; one study even estimated over a million had died. When much of the city of Fallujah was razed and hundreds killed by US forces – who used white phosphorous, which strips the skins from people’s bodies – the cruise missile liberals fell largely silent.

All this blood, and for what? In 2005, Ayad Allawi – a former CIA agent originally installed as Iraqi Prime Minister – argued that “people are doing the same as [in] Saddam’s time and worse”. Human Rights Watch warns that “the Iraq people today have a government that is slipping further into authoritarianism”, listing “draconian measures against opposition politicians, detainees, demonstrators, and journalists, effectively squeezing the space for independent civil society and political freedoms in Iraq”. Iraq is now 150th out of 179 countries in the World Press Freedom Index, worse than Russia or Zimbabwe; and the US government-funded Freedom House rates Iraq 6 for civil liberties and 6 for political rights, with 7 being the worst. No wonder Tony Dodge, an Iraq expert at the LSE, warns that “Maliki is heading towards an incredibly destructive dictatorship”.

Easy for me to berate, you might think: I didn’t live through the horror of Saddam. Listen to the Iraqi people, then. A detailed poll by Zogby at the end of 2011 revealed that just 30 per cent of Iraqis felt the invasion left them better off; 23 per cent felt things were just the same, and 42 per cent said they were worse. Among the Shia, 70 per cent felt things were worse or just as bad as under Saddam; it was 79 per cent among Sunnis. Winning hearts and minds indeed.

The hawks were wrong on every count. Wrong about the weapons; wrong about being greeted with flowers; wrong about the human cost; wrong about Iraq becoming a flourishing democracy. But I remember the euphoria I felt on 15 February 2003 with grief. We did not stop an inferno which began a month later, consuming the lives of hundreds of thousands, including 179 British soldiers. Incalculable misery; incalculable horror. It must never happen again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments