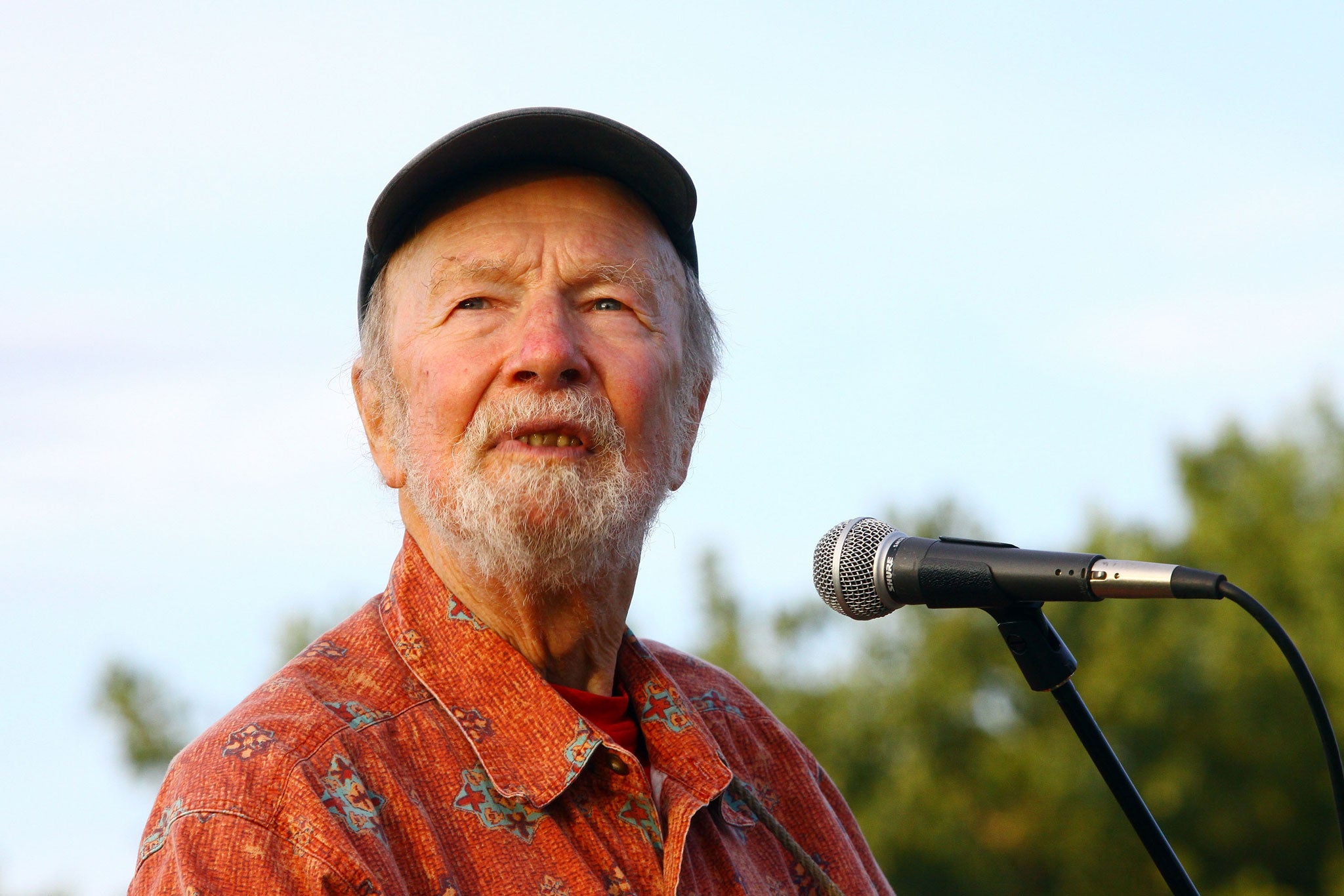

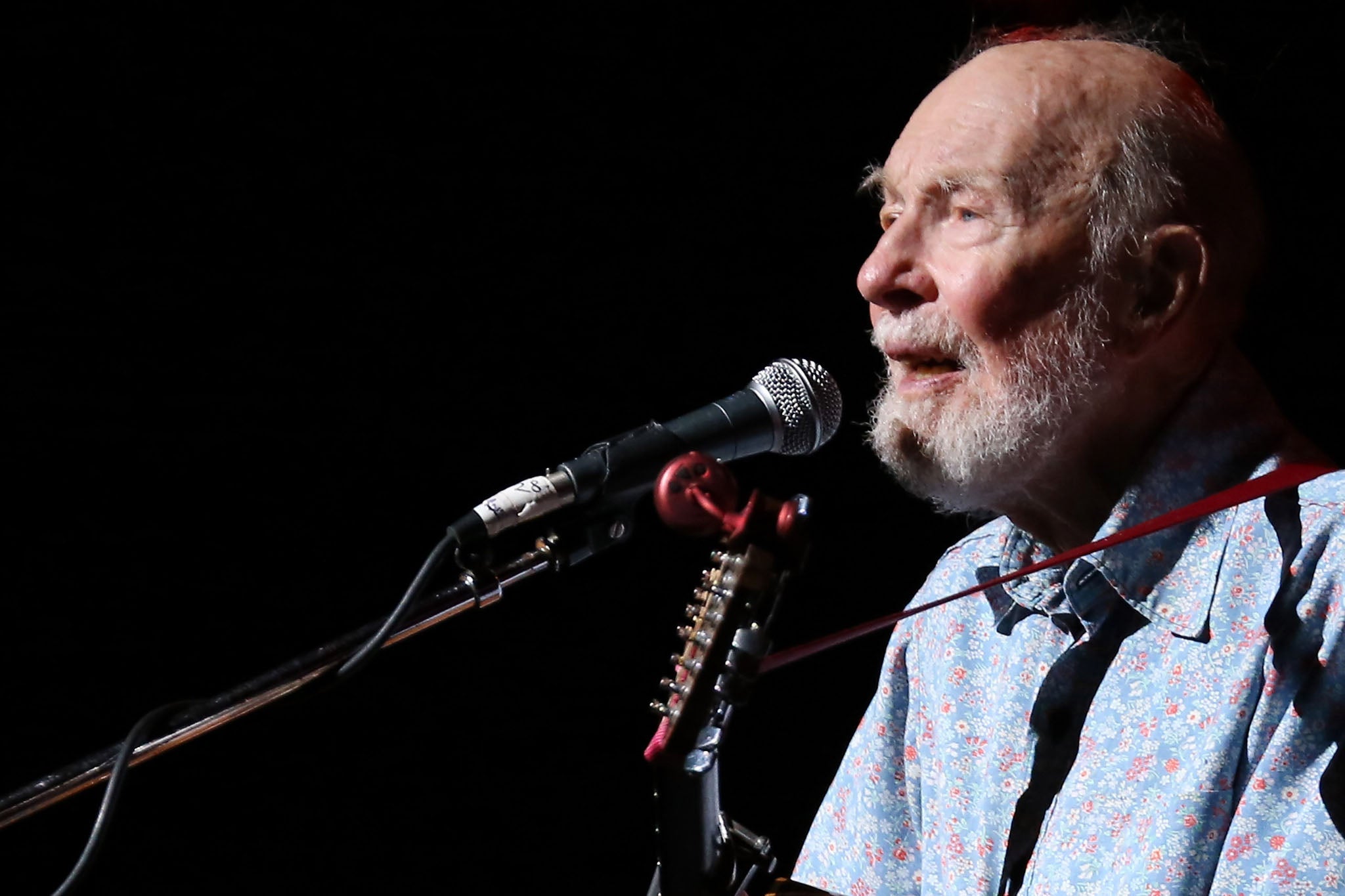

We can no longer protest like Pete Seeger

He was a hero, yet I was unable to watch him without a feeling of irritation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An anti-capitalist demonstration is in progress. The talk is of evil bankers, of outrageous bonuses, of the general ghastliness of politicians. As a police cordon moves towards the demonstrators, a slim, earnest young man holding a guitar stands up and, in a defiant, middle-class voice, begins to sing a well-known song of protest, “If I Had a Hammer”.

Soon the crowd is singing along. “I’d hammer out danger! I’d hammer out a warning!/ I’d hammer out love between my brothers and my sisters/ All over this land.”

It doesn’t work, does it? Even if the political protest song was one of today, the scene is implausible. The death this week of Pete Seeger, once described as “the Pied Piper of dissent”, is a reminder not only of his own extraordinary life, but that the kind of song for which he was most famous now belongs firmly in the past.

It is not that the enemies which Seeger so bravely opposed throughout his life – the bosses, the generals, the polluters – are no longer there, but that the rest of us have changed. Life has become more complicated, and music has reflected that difference. Remembering Seeger’s courageous spirit, it is tempting to conclude nostalgically that there was more idealism 30, 40 or 50 years ago. In fact, the truth is that we, and the music, have become a little more adult.

Seeger’s life was a straight line of integrity and virtue. A non-drinking, non-smoking vegetarian, he evangelised on behalf of the same egalitarian, left-wing views throughout his life. When American culture was at its most blinkered and bigoted, he championed the music of outsiders. In his deceptively mild-mannered way, he stood up to the right-wing bullies who are so often in power in America, notably giving the lie to the assumption that liberal views are by their nature anti-patriotic when appearing before the House of Un-American Activities Committee in 1955. “I greatly resent this implication that some of my opinions, whether they are religious or philosophical … make me less of an American,” he said.

His songs had a message of peace, love and social justice as simple as the chords on which they were played. If people sang along, he believed, they could help change the world. He was a hero – and yet I was never able to watch his performances without feeling a stirring of impatience. For me, he was irritatingly virtuous.

Pete Seeger talked the talk and walked the walk. Who comes close today?

Pete Seeger obituary: Musician and activist dies aged 94

We shall be heard : Images of American Activists

When Tom Lehrer, a far more discomfiting songwriter, described “Little Boxes”, Seeger’s satirical take on suburbia, as “the most sanctimonious song ever written”, he was on to something. Sometimes moral superiority can be rather too easy. Returning fire on the folkies by performing his own satirical ditty, called “ The Folk Song Army”, Lehrer would introduce it by sardonically pointing out that it must take a lot of courage to stand up and sing in favour of things everyone else opposed – peace, justice, brotherhood. “Join the folk song army!” the song went. “Guitars are the weapons we bring/ To the fight against poverty, war, and injustice/ Ready ... aim ... sing!”

It was the Lehrer view which prevailed. The singalong politics of demos, sit-ins and folk concerts, quasi-religious occasions at which every member of the audience, eyes shining with self-righteousness, sang that this land was their land or that they would overcome, began to go out of fashion. Those songs evoked a world of baddies and goodies, of them and us, of bastards in power brutalising us, the ordinary people, their poor, oppressed victims.

Attitudes began to fray in the mid-1960s. Bob Dylan, the archetypal protest singer, realised that the easy certainties that this kind of folk music brought with it were restricting, perhaps even dishonest. The last thing he wanted was to be the voice of a generation; instead he would sing about himself. The moment at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival when Seeger wished he could have taken an axe to the power cable supplying Dylan and his band’s electric guitars was not merely, as he later claimed, about wanting to hear the words. It was a rage against change.

From then on, protest turned inwards, became less universal, more local. Its target was the culture and personal behaviour rather than politics. By the 1990s, Dylan’s great anthem of protest “The Times They Are a-Changin’” could be used in TV commercials, first for an accountancy and then an insurance firm, without causing too much upset. As we have become less politically polarised, so protest music has had to evolve. Today most sensible people are suspicious of black-or-white moralising. They know, in their hearts, that the recession was not entirely caused by evil bankers, that politicians are not all self-interested and greedy, that life is complicated.

The songs have become more nuanced, ironic. There is room for ambivalence. Famously, Bruce Springsteen’s angry “Born in the USA” was embraced as a patriotic song by Ronald Reagan. Songwriters such as Randy Newman and Elvis Costello satirise racism, cruelty or gender prejudice from the inside rather than condemning from a position of easy moral certainty.

It has all become an interesting muddle. When, at the end of last year, Lily Allen released “Hard Out There”, a song attacking the moronic sexism of the music industry, the music was as highly produced, and the video as sexually frank, as her targets. It makes for more uncomfortable listening than a traditional protest song but is none the worse for that.

The days of old-fashioned musical dissent may be over, but the fact that we are all more aware of how governments work, that a level of scepticism is everywhere in the culture, is largely thanks to the noble efforts of guitar-toting radicals like Pete Seeger. In the end, the folk song army won a victory of sorts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments