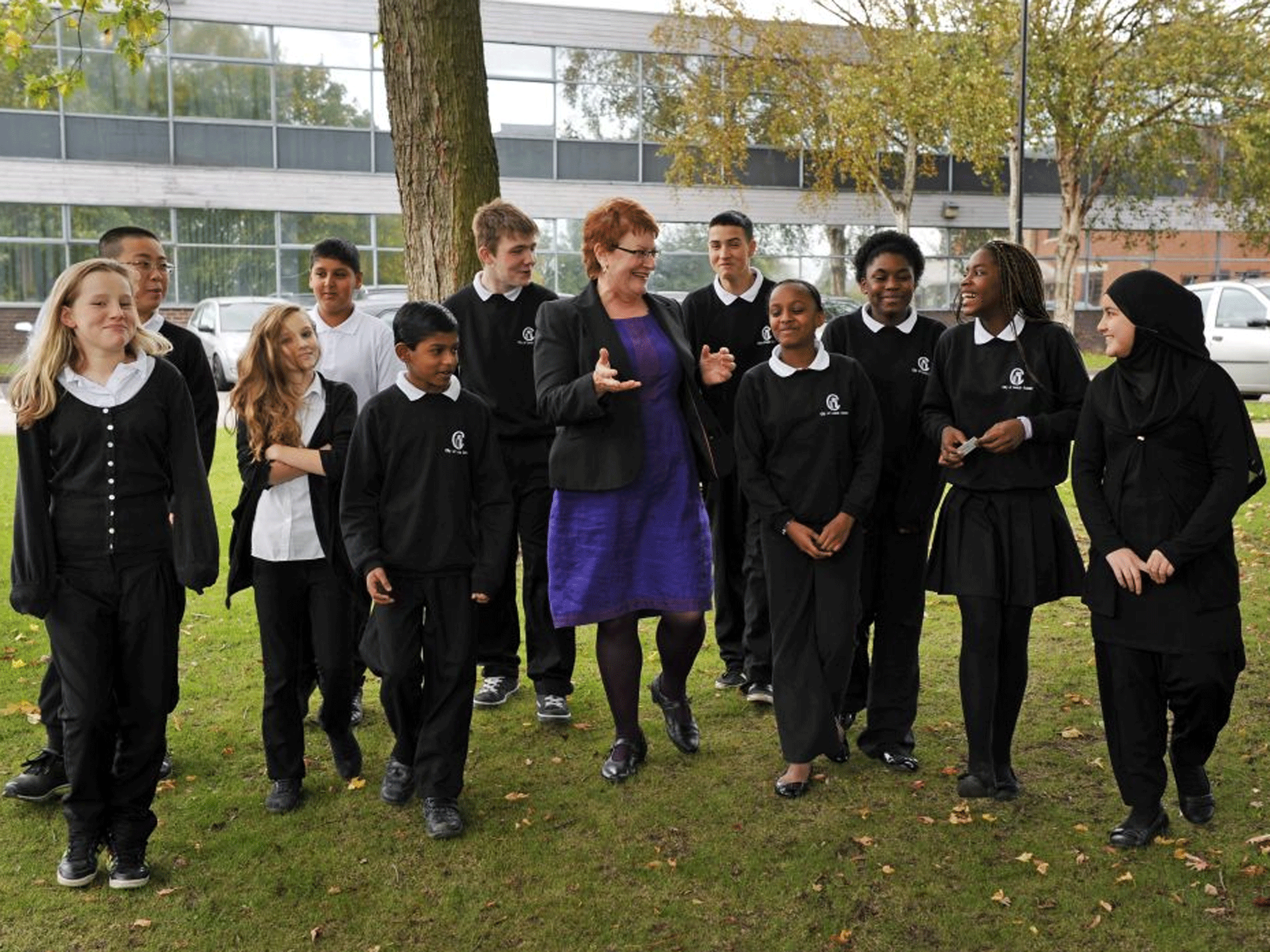

Untwisting tongues: Every student will benefit from the City of Leeds School's decision to teach English as a second language

I’ve long thought that such an approach would really help

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Three cheers and more for City of Leeds School which has decided that the best way of teaching English systematically and effectively is to teach it as a foreign language to everyone. It’s an innovative and inspired idea. If you want to hear English spoken really well then listen to a well-taught foreigner. Many of them put native speakers to shame.

Around 85 per cent of the pupils at City of Leeds School are not first language English speakers. And, according to headteacher Georgiana Sale, many of the remaining 15 per cent are weak in literacy skills. So teaching English from first principles, including its grammar and spelling, is clearly a very sensible approach.

English is notoriously badly taught in this country and I speak as a former English teacher of very long experience. Yes, we are pretty good at literature and creative writing but, in general, very poor at the nuts and bolts. And that has been the case for a long time. I suppose I am personally strong on grammatical issues. I’ve written books which help children and teachers with it after all. But I didn’t learn it in English lessons even in the 1950s and 60s. Instead I acquired almost everything I know about language in Latin classes – and wasn’t I lucky to have them? Most teachers of English working in secondary schools today simply don’t have that underpinning so they can hardly be blamed for not passing it on.

But people who have trained to teach English as a foreign language are a very different breed. The subject matter is complex and rigorous and the ones who grew up in Britain, at least, have to work long and hard to acquire it. It seems to come more easily to other European nationals who have learned their own languages formally and so have a grammatical infrastructure to apply to other languages. A verb is a verb in any language after all.

Good teachers of English as a foreign language – known as TEFL – then develop high level skills in explaining and demonstrating the language so that many of their pupils acquire useful formal communication skills both oral and written. And I’ve long thought that such an approach would really help many of our English-speaking secondary pupils. Yes, of course, if they’re first language English speakers they will already be able to communicate within their own narrow social circles. But they need very much more than this if they are to prosper in the world.

There’s another reason why I applaud the decision of City of Leeds School. Those 85 per cent represent 55 nationalities and speak 50 different languages from Czech to Urdu. That’s a wonderful resource for a school. Immigrants are a bonus, not a cause for handwringing. I remember teaching a class in which 18 languages other than English were spoken and it led to some fascinating discussions which benefited everyone in the room. But, when pupils’ English is weak or non-existent it makes life very difficult indeed for the teacher of, say, geography or maths who speaks only English. He or she cannot do the job properly until everyone in the class can understand what’s being said – so the school has a responsibility to make this happen as soon as possible. It’s great to have all that cultural diversity but you need a common language too.

Inevitably there has been some quite nasty racist hostility to City of Leeds School’s new policy. There’s a cheap anti-immigration political point to score here. The truth is of course, that English would have been weak in this school long before the immigrants arrived. Their presence merely focuses attention on every single pupil’s entitlement to high quality English teaching which gives all students a clear basis for understanding how the language works. And now they’re getting it. Win win.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments