Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is to the painter of a portrait of a young man called Dorian Gray that Oscar Wilde’s best remembered lines are said: “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

Even so, the artist cannot be persuaded to exhibit his work. The pictures go in the attic.

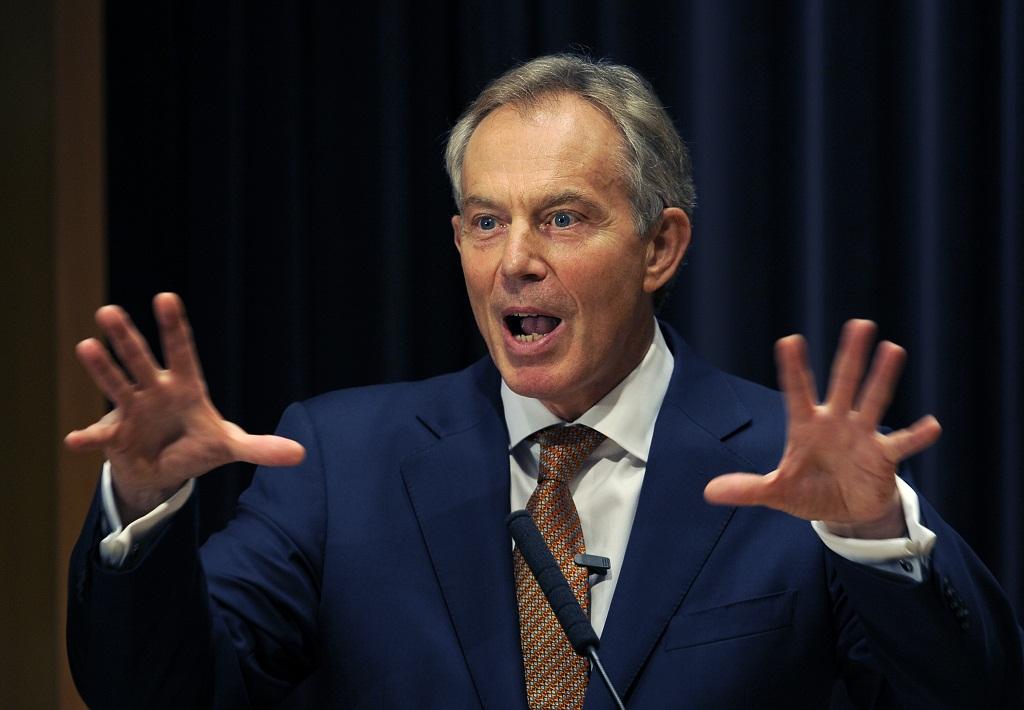

Tony Blair is not a man afflicted by such self-doubt. His is a public that has never been left wanting. But for such people there is a worse fate, which Wilde did not consider: to talk, but not to be listened to.

Dorian Gray’s portrait grows hideous unseen in the dark, disfigured by the public sins of the man himself. For a large swathe of people, who are determined that their final validation will come tomorrow morning with the publication of the Chilcot Report, whatever it says, the picture of Tony Blair has turned repulsive in the full glare of the public spotlight.

In the 13 years since British forces joined American in the shock-and-awe invasion of Iraq, Tony Blair has variously made overtures to history, to God and, occasionally, to the public, in the hope of a favourable judgement. Thirteen years is a long time, and as more time passes history narrows to an increasing certainty that the judgement will not be favourable; that the lasting legacy of a decade in office will not extend beyond that decision to wage a war to topple a tyrant and destroy his lethal arsenal that, in the end, wasn’t there.

Dorian Gray could seemingly do no wrong. Tony Blair can do no right. That he won a third general election with breathless ease two years after the invasion seems to count for nothing. That the majority of his time is spent on unpaid, important work in the Middle East for which he receives no praise and countless ridicule doesn’t matter either. That his various foundations on faith and governance appear to have the bravery to take on the world’s major challenges and stress-test the ideas that might solve them appears of no concern to anyone.

To talk but to not be listened to is the long ever-after of the Blair parable. “The party is walking eyes shut, arms outstretched, over the cliff’s edge to the jagged rocks below,” he said last August, the most successful leader in the party’s history, begging his members not to elect Jeremy Corbyn. He was right, of course, but no one listened.

The longstanding joke on Blair is that if he wants to have any effect, he should argue the direct opposite. “Why would I listen to that war criminal?” said many a newly minted Corbynista at the time; many of these now see the jagged rocks and have changed their minds. “When people like me come forward and say, elect Jeremy Corbyn as leader and it will be an electoral disaster,” Blair wrote in the Guardian, “his enthusiastic new supporters roll their eyes. It makes them more likely to support him”.

Many such people now even blame Corbyn for defeat in the EU referendum.

And, on the subject of Europe: “The Leave campaign has completely failed to explain how if we leave Europe we can still have access to Europe's market – vital for UK jobs. That's a risk that our country simply can't afford to take,” said Blair, three days before the poll, perfectly voicing the concerns of, to take just one example, thousands of Nissan workers in Sunderland who, we are told, didn’t understand what they were voting for and would change their minds if they could.

These occasional interventions from Blair are more often than not met with the publication of new polls, of the type undertaken earlier this year by a think-tank called British Future, which reported that 82 per cent of people minded to vote to Leave “completely distrusted” what he had to say. This data was reported in the Telegraph under the headline: “Tony Blair can help keep Britain in the EU by shutting up.”

He didn’t take their advice.

After seven years, a rumoured 2.6 million words and a total cost of more than £10m, Sir John Chilcot’s report will not give the validation the Blair-haters demand. It is not within its authority to brand him a war criminal. It is likely to criticise him heavily for the rush to war in early 2003, when by late 2002 the evidence from UN weapons inspectors was sufficiently inconclusive to, well, dwell a pause.

It will also condemn him for failing to foresee or to consider the aftermath of regime change, an inevitability foreseeable by even the idlest political science undergraduate. You don’t even need to have read the York Notes on Edmund Burke or Lenin or Theda Skocpol to understand that a post-Saddam Iraq cannot be left even vaguely to chance.

In the last few weeks as, via the usual round of interviews and public appearances, Blair has continued his slow motion descent to what may yet become, one day, a public acceptance that the Iraq decision was the wrong decision, even on the evidence at hand at the time, he has missed no opportunity to state that he will “play a full part” in the debate that will come.

He will argue that he is not a war criminal. That Saddam was a war criminal. He will point out the folly in the idea that the current disaster that is Iraq can all be blamed on the decision to invade. Forces unforeseen and unforeseeable have swept the region in the years since, the most seismic of which came in early 2011, via a self-immolating Tunisian fruit and vegetable seller, and without any input from the west. If there had been no invasion, Iraq would not still be living in 2002.

It’s possible that this the soon-to-be-launched Blair Offensive will have some impact, but unlikely that it will affect the overwhelming public consensus. It is a measure of how low his reputation has been allowed to plummet – under the constant narrative of vast accumulation of wealth, consulting tyrannical leaders and speechifying to anyone that can afford it – that he rarely bothers to defend himself against such claims any more.

Indeed, it seems more likely that his words will continue to have the opposite effect. Such, he knows, is the Blair curse. And not even a complete mea culpa will, in the decades to come, ever lead history to see beyond the hideous painting and the handsome, young reforming Prime Minister dead on the attic floor.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments