The idea that the NHS should fund everyone's boob jobs reveals a much deeper problem

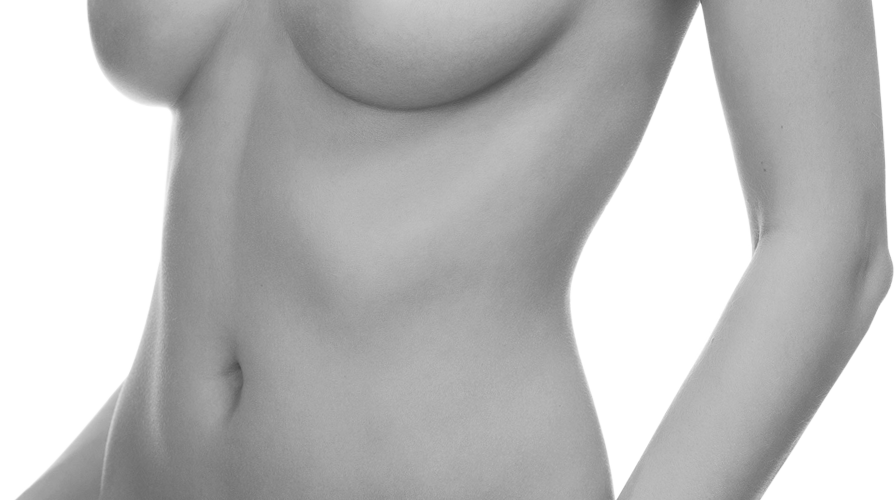

Society's definition of perfection - big breasts and small noses - is far too narrow

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is difficult not to feel sorry for Josie Cunningham. Bullied for being flat-chested, she went to her GP to request breast enlargement surgery on the NHS. After the operation, she was left feeling self-conscious at the size of her new breasts, which had been increased from 32A to 36DD. After asking for a reduction, also on the NHS, her case was widely reported – the young woman who wanted to be a glamour model became an unwitting poster-girl for “free” cosmetic surgery. In a sense, she was bullied again as she became the subject of outrage from some newspapers for “daring” to ask the taxpayer to fund her operations.

I don’t know the full details of her case, but what kind of surgeon decided it would be a good idea to give a woman barely out of her teens such a dramatic change in her breast size? It is not surprising she felt self-conscious. The NHS supposedly funds cosmetic surgery only in extreme cases, but it is clear the definition of extreme is elastic, and that there are plenty of doctors out there who are not taking seriously the psychological state of their patients. The website boobjobsontheservice.co.uk purports to offer sensible advice about which cases will be paid for, but the fact that it exists at all suggests it is providing a service in a growing market.

So Jeremy Hunt’s announcement this week that he wants to see an end to the NHS funding cosmetic surgery is welcome, particularly when health service funding is being cut in real terms. At £5,500 for a breast operation and £750 for a tummy tuck, several million pounds are being spent every year on NHS-funded cosmetic surgery. This may be only a tiny fraction of the £100bn-plus annual NHS budget, but when other procedures and treatments are denied to seriously ill patients on cost grounds, it still matters.

Of course, the new guidelines should ensure that surgery remains available for reconstruction after breast cancer surgery, and for severe breast reduction cases, where the woman is suffering from back problems, or nose surgery where the patient has difficulty breathing. In other cases, it should still be available to those who suffer from serious mental health issues as a result of how they look. Nobody would criticise that. In the case of Ms Cunningham, she would possibly still have the right to surgery if, as a result of her bullying, it could be proved that her mental health suffered. But it is clear that surgeons need to be more sensible and not change a young woman’s body shape so dramatically that, as in Ms Cunningham’s case, she is left more self-conscious than she was before.

Beyond the necessary cases, then, the Health Secretary is absolutely right to crack down on a system that is clearly letting patients have cosmetic surgery on the NHS because they are merely unhappy with how they look.

But this problem goes further than changing NHS guidelines. We have to look at the reasons why, as a society, individuals – particularly teenagers and young women – feel they have to meet a very narrow definition of perfection, which invariably includes having large breasts and a small nose. As someone who was taunted at school for being both flat-chested and having a large nose, I sympathise with people who are bullied or are unhappy with their bodies. It is obviously easy for me to say now, at the ripe old age of 40, but I am relieved that I didn’t have any surgery.

If it is any reassurance, at some point the bullying stops and you learn to like the way you look. But my words cannot outweigh the enormous pressure from everywhere – Twitter, Facebook, newspapers, magazines and TV programmes like 10 Years Younger. This is an ancient argument – 20 years ago, when I started university, there were stories about my generation coming under pressure to copy the “waif look” of Kate Moss and Jodie Kidd. The last decade the “desirable” body shape has been closer to Katie Price and Kim Kardashian. The faulty implants scandal of two years ago may lead to a fall in women wanting breast enlargement – private or NHS-funded. But while the “perfect” breast size has changed over the years, the pressure to meet this perfection has not, and I am not sure the Health Secretary can do anything about that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments