The fatwa against Salman Rushdie failed, and so will the extremists who killed in Paris

However, the defence of freedom is a rocky road, not a walk in the park

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This week there was a quiet victory for freedom of expression against the forces of bloodthirsty fanaticism. On Thursday, without much prior fanfare and to launch a general republication of the author’s back list, the Vintage imprint of Penguin Random House released a new edition of a landmark novel of the 1980s.

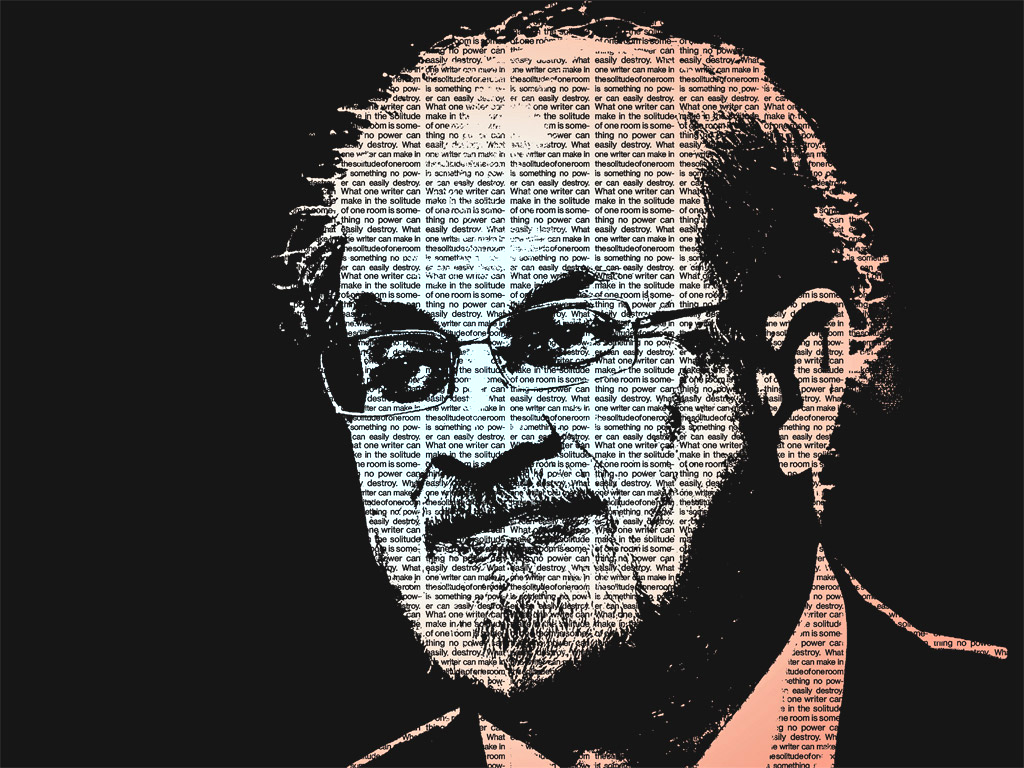

It is Sir Salman Rushdie’s tragicomic epic of migration, rootlessness and the quest for identity, The Satanic Verses. Almost 26 years after the Iranian fatwa placed the writer under sentence of death, led to the slaughter of his Japanese translator and grave injuries to both his Italian translator and his Norwegian publisher, Rushdie and his fiction live and thrive.

The fatwa failed. Just as the murderers who killed 10 journalists and two police officers at Charlie Hebdo will fail. Some of the warmest words of solidarity in the wake of the atrocity have been the simplest. In the Paris daily Libération, co-editor Laurent Joffrin wrote that: “We’re not soldiers. But we defend our craft and our vocation: to help the reader feel like a citizen. It’s not such a big deal, but it’s something.” Now, more than ever, “We know why we’re doing this job.”

In Britain, too, readers need to feel like citizens. The carnage in Paris should not slip from our minds as the headlines fade. In France, the aftermath of grief and sympathy made natives and foreigners remember that freedom of speech is not merely a decorative accessory to democracy. It underpins all other principles – including a protected diversity of custom and belief. If France has its Voltaire and, before him, that even greater prophet of doubt, reason and tolerant goodwill, Michel de Montaigne, then we too have our sacred texts of liberty. I went straight back to Areopagitica, the peerless tract written by John Milton in 1644 just as Parliament threatened to reimpose press licensing on revolutionary England: “Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.”

Yet, as the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta approaches, freedom in Britain does not rest in trustworthy hands. Echoed by Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg, David Cameron assured us that “We stand squarely for free speech and democracy”. So prove it. Legislation, rhetoric and security-service empire-building give exactly the opposite impression: that the British political class dislikes, distrusts and will whenever it can undermine freedom of expression.

When I interviewed Rushdie about his memoir of the fatwa years, Joseph Anton, he explained that, until Robin Cook took charge in 1997 and sought an exit from the impasse with Iran, the Foreign Office had treated him not as a martyr to liberties but a very naughty boy: “The sense that I’d made a terrible nuisance of myself and didn’t deserve any kind of major effort was there in quite a lot of the civil servants that I met.”

Then came 9/11, the Iraq debacle, the “war on terror” and twin drives to clamp down on Islamist extremism and to pacify faith communities with stringent laws against “offence”. In 2004, Home Office minister Fiona Mactaggart conspicuously refused to support the theatre that staged Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti against hooligans and wreckers who claimed to act in the name of Sikhism. During the New Labour years, social disciplinarians such as David Blunkett, John Reid and Jack Straw chilled liberty at every turn. Counter-terrorism licensed every intrusion, with a crude trade-off. Alongside the targeting of Muslim communities in the hunt for suspected plotters (a heavy-handed strategy that still failed to block the 7/7 attacks) went authoritarian concessions to self-appointed representatives of faith.

On the one hand, with MI5 and Home Office collusion, the illegal “Project Champion” put residents in Muslim neighbourhoods of Birmingham under blanket surveillance from 200 CCTV cameras. On the other, in 2005 came the lamentable attempt to strangle the critique of religion via the first draft of the Racial and Religious Hatred Bill, with its scattergun provisions against “insulting” belief. It took an energetic and well-organised revolt of artists, writers and comedians to knock sense into that statute.

The final Act was not only strictly limited to the incitement of hatred. It boasts a unique declaratory amendment (29J). This affirms that “Nothing in this Part shall be read or given effect in a way which prohibits or restricts discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse of particular religions or the beliefs or practices of their adherents, or of any other belief system or the beliefs or practices of its adherents, or proselytising or urging adherents of a different religion or belief system to cease practising their religion or belief system”.

Thanks to English PEN and its turbulent scribes and thesps, we now enjoy that much at least of a written constitution to buttress any criticism of organised faith. However, the amended Bill, imported from the House of Lords, passed by just 288 votes to 278 when it returned to the Commons in January 2006. Only a handful of Labour rebels ensured its passage.

Since May 2010, Theresa May has built on New Labour’s repressive foundations. For mainstream politics, the clear and present danger of jihadi violence warrants one controlling measure after another. Free speech enters muddy waters here. Anyone can hold a candle, or a pen, for a murdered cartoonist. Wannabe Isis warriors whose websites now come under supervision and interdiction do sometimes “glorify” holy war in word and image. Who draws the line between speech and act, and where? Free-speech fundamentalists – in whose ranks I march, out of step, as a grumbling fellow traveller – have to negotiate not just the gentle slopes of sentimental solidarity but also that treacherous scree where mouthy militancy can slide into blueprints for bloodshed.

That said, freedom needs its party in Britain. It no longer has one. Hobbled by coalition woes, the Liberal Democrats now stake their survival on a ragged patchwork of voting blocks rather than any libertarian ideal. Ukip, the Greens and the SNP look alike in that they seek communal and conformist remedies for the paralysis of politics. As for the sharp end of media freedom, virtually all nice, decent, public-spirited people warmly support the Royal Charter that passed into law in 2013 in the wake of the Leveson report into press abuses. Surely only a sleazy tabloid rogue would dissent. I raise my hand.

Under its terms, non-registration with an approved self-regulator licensed by the “Recognition Panel” opens up a publication to exemplary damages. This strikes me as nakedly oppressive: a menace euphemised by the Hacked Off campaign when it speaks of the penalty of “competitive disadvantages” for non-registration.

Hugh Tomlinson QC’s analysis of the Royal Charter confirms that, even if an unregistered outlet goes to law and wins, “then the courts would deprive the publisher of its costs in any reasonably arguable legal claim against it, even if the publisher is successful”.

Utter confusion surrounds the definition of a “relevant publisher” who must sign up or face extra penalties. English PEN argues that “relevant publishers” will have to choose “between joining a recognised regulator or risking exposure to high court costs, even in cases that they win. This may make publishers who decide not to join a regulator more likely to self-censor in order to minimise their exposure to the risk of being sued”.

Despite this chilling message, almost every thoughtful, serious, ethically upright cultural figure in Britain seems to endorse the Royal Charter. The risk of bankruptcy for some scurrilous non-registered website or newsletter may seem remote.

But that so many people who would raise a pen for Charlie Hebdo feel content with this prospect should alarm free-speech advocates. Section 34 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013 allows punitive damages against unregistered media if “the defendant’s conduct has shown a deliberate or reckless disregard of an outrageous nature for the claimant’s rights” – such as, for instance, persisting in the publication of impious and “offensive” cartoons? When the fight turns nasty, genuinely free speech in John Milton’s nation has few all-weather friends. As the poet wrote about any press “licensor”, “I endure not an instructor that comes to me under the wardship of an overseeing fist.”

A true concern for free expression has to go further than mourning those who died after mocking a creed not your own in a country not your own. “Je suis Charlie” must mean more than that. It may require that you stand beside the kind of scoffers, snoopers and loudmouths who will upset, offend and possibly disgust you. Beside, say, the red-top hack who, legally and truthfully, exposes the private indiscretions of a celebrity or politician whom you much admire. Beside the sociopathic bigoted tweeter who needs to be censured, educated – but not jailed.

Beside the consenting-adults pornographer whose targeting by preposterous new rules against “face-sitting” or female ejaculation may (as libertarian lawyer Myles Jackman writes) act as “the canary in the coalmine of free speech”. Even, perhaps, beside the fantasy jihadist who in his lonely bedroom applauds online, although he would never emulate, the sort of atrocity that we saw this week.

The defence of freedom is a rocky road, not a walk in the park. We owe it to the Charlie Hebdo victims not to wallow in zero-cost pieties. Above all, British liberties need a solid parliamentary home. Facing near-oblivion in May, the party of Mill, Gladstone and Keynes should consider returning to its roots. The Lib Dems have nothing to lose.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments