The evidence is clear: the Home Secretary and the Conservatives talk nonsense on immigration

There appears to be little association between non-EU immigration and employment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This week the Coalition started to fight like ferrets in a sack over their failed migration policy. Ukip is likely to take advantage in the May European elections.

To say the Coalition is in a terrible muddle understates the disaster they have created for themselves as their “reducing net migration” policy has fallen apart. Infighting and finger-pointing have now ensued. It didn’t help that the newly published migration data showed that David Cameron’s promise to dramatically lower net migration had disastrously failed. The much-heralded downward trend in the early years of the Coalition has now reversed itself.

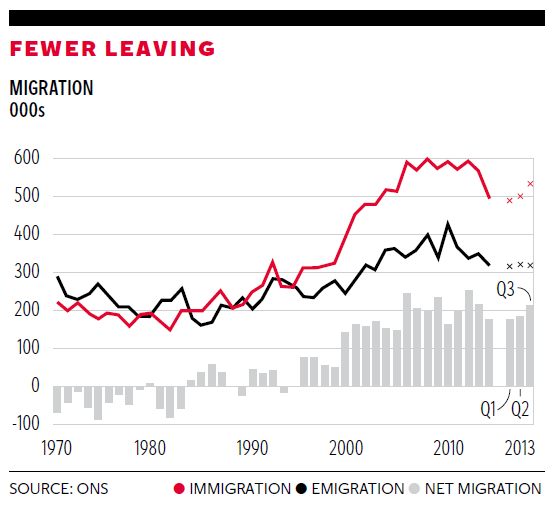

The latest Migration Statistics Quarterly Report, February 2014, reported a provisional estimated net flow of 212,000 long-term migrants to the UK in the year ending September 2013, a statistically significant increase from 154,000 in the previous year. The chart illustrates the time series pattern: during the 1960s and 1970s, there were more people emigrating from the UK than arriving to live in the UK. During the 1980s and early 1990s, net migration was positive at a relatively low level in the majority of years. Since 1994, it has been positive every year and rose sharply after 1997. During the 2000s, net migration peaked in 2004/05, in part as a result of immigration of citizens from the Accession Countries that joined the EU in 2004. Since the peak, annual net migration has fluctuated between around 150,000 and 250,000.

The chart makes clear that despite falls in net migration in 2010 through 2012, the subsequent trend is up, in large part driven by the fact that fewer UK citizens are emigrating, presumably because Spain and other countries are less attractive than they were pre-recession. The Coalition didn’t seem to realise it was going to be especially hard for it to control the number of Brits leaving, let alone the number of EU citizens arriving.

Net migration of EU citizens doubled from 65,000 in the year ending September 2012 to 131,000 in the year ending September 2013, which is a statistically significant increase. Conversely, the estimate of net migration of non-EU citizens has declined over the last few years. Although the recent fall to 141,000 in the year ending September 2013 from 160,000 in the previous year was not a statistically significant change, non-EU net migration remains at a lower level relative to the 2005 and 2010 peaks.

The Coalition recently lost their Immigration minister, Mark Harper, who was forced to stand down after he discovered his cleaner did not have permission to work in the UK. His replacement, James Brokenshire, last week delivered his first speech as Immigration minister to almost universal condemnation, where he claimed that better-off families and big businesses had benefited most from the recent arrival of foreign workers in Britain. By contrast, he argued that “ordinary, hard-working people” have not felt the economic benefits of immigration. Vince Cable, in contrast, has made clear he is “intensely relaxed” about mass immigration, which lowers the price of goods to the benefit of all. So that’s clear, then.

Then there was all that fuss started by Chris Cook on BBC2’s Newsnight, who discovered that a report on the lack of displacement effects of migrants was being suppressed by Downing Street. It apparently showed a weaker link between immigration and unemployment than the Government had claimed. The Home Secretary, Theresa May, claimed in 2012: “There is a clear association between non-European immigration and employment in the UK. Between 1995 and 2010 … for every additional one hundred immigrants, [academics] estimated that 23 British workers would not be employed.”

The basis for this contention was an earlier econometric study by the Government’s independent Migration Advisory Committee (MAC), published in 2012, on the impact of migration on the employment of native British workers. It concluded, contrary to a number of other analyses, that there was, at least for some immigrants and in some circumstances, a negative impact. Matt Cavanagh, then at IPPR, and Jon Portes at NIESR were highly critical of the findings.

Lo and behold, the previously hidden report was suddenly published a couple of days later, and boy was it embarrassing for Dave and his Eton pals. It was written by two authors employed at the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills and three from the Home Office.*

The authors conclude that there is “relatively little evidence that migration has caused significant displacement of UK natives … when the economy is strong.” While it does find “evidence of some labour market displacement, particularly by non-EU migrants in recent years when the economy was in recession”, it adds this is a short-term effect, one that is “likely to dissipate”.

They further conclude that “there has been little evidence in the literature of a statistically significant impact from EU migration on native employment outcomes”. Where displacement effects are observed, the authors found these tend to be concentrated on lower-skilled natives.

The authors of the Government’s new study reworked the results obtained in the earlier MAC study and found that when data from part of the period of economic downturn (2009 and 2010) were omitted, the impact of non-EU migration was no longer statistically significant.

The finding that displacement impacts may be heavily influenced by economic conditions the authors claim “reconciles the MAC findings with much of the previous literature” that prior to 2008 the bulk of the evidence pointed to little impact of net migration on labour market outcomes for UK natives. So downturns produce atypical results that shouldn’t be generalised from.

So UK civil servants have confirmed that there appears to be no clear association between non-European immigration and employment in the UK. Between 1995 and 2010, for every additional one hundred immigrants, zero British workers would not be employed. Theresa May was talking baloney.

* “Impacts of migration on UK native employment: An analytical review of the evidence”, Ciaran Devlin and Olivia Bolt (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills) and Dhiren Patel, David Harding and Ishtiaq Hussain (Home Office).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments