The curious tale of the Swedish Soviet spy and the sheltering Druze

‘We’ll never forget your support for the cause of the Soviet people and our common struggle against imperialism’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

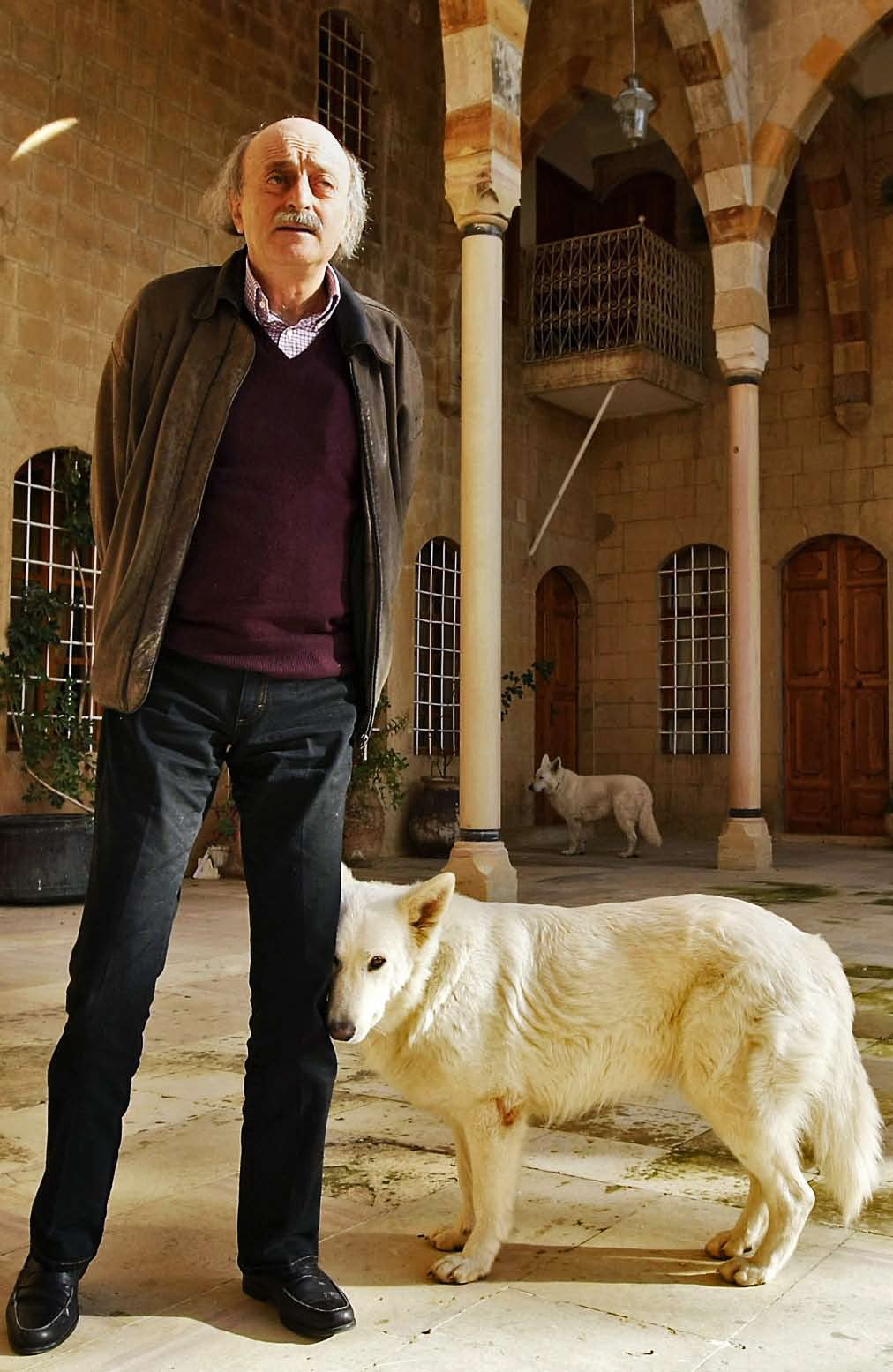

Your support makes all the difference.More than 20 years ago, Walid Jumblatt, the Lebanese Druze leader, admitted to a Swedish diplomat that he hid a Soviet spy – a Swedish intelligence officer – near his Lebanese mountain home at Moukhtara in the early 1990s at the request of a senior Russian intelligence officer. I was sitting that evening on Jumblatt’s lawn, agog.

The conversation was friendly – the Swede, like me, was a dinner guest at Jumblatt’s ancestral home, a palace of ancient stone walls, trickling streams, fine food and an entire Roman mosaic floor. Jumblatt and the Swede both regarded his sheltering of Soviet agent Stig Bergling as a relic from Cold War history. There was much joshing and laughter over the rather odd story of Jumblatt’s protection of a Swede who worked for his country’s national intelligence agency and sold 15,000 military documents to Moscow.

“Yes, he used to have lunch with us here,” Jumblatt said with a wave of his arm across the lawn. “I apologise to Sweden.” The diplomat half-bowed with conscious irony. I snorted at the Swede’s exaggerated “politesse”.

But Bergling has just died in Stockholm at the age of 77, and Walid Jumblatt – self-declared enemy of Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian regime and the victim of an assassination attempt during the 1975-90 civil war – has now disclosed much more about his role in sheltering the venal spy, who was sentenced to life imprisonment for espionage but escaped captivity in Sweden during a conjugal visit to his wife in 1987. A few years later, Jumblatt now says, he received a “friendly visit” from General Vladimir Ismailov, the deputy director of Soviet military intelligence.

Jumblatt’s account, in a series of emails to friends and in an article in his own “socialist” party newspaper Al-Anba’a, describes Ismailov as “impressively tall with red hair [and a] big moustache”; he was accompanied to the Chouf mountain town of Moukhtara “by another official, most probably one of his assistants and a common friend”. Talks between Jumblatt and the Russians began “after five or six shots of vodka, and numerous toasts to Lebanese-Soviet friendship, and to the Progressive Socialist Party [the official title of Jumblatt’s almost Ottoman Druze alliance] and the Soviet Communist Party’s common fight”.

Not for nothing does the intellectual Jumblatt sometimes revel in the title – which I gave him in an Independent report in 2004 – of “the world’s greatest nihilist”. He clearly enjoyed telling his own story of Bergling’s secret hideaway south of Beirut.

“Then General Ismailov told me: ‘Comrade Walid, you are a great friend of the Soviet Union, and we will never forget your position supporting the cause of the Soviet people and our common struggle against imperialism’ – I presume some of you know this kind of terminology.

“General Ismailov asked me if I could shelter somebody at Moukhtara. How could I refuse? The Soviets provided me with hundreds of scholarships [for the Druze], trained the militia of the Socialist Party by the thousand in their bases and provided us with the equivalent of $500m of weapons and ammunition between 1979 until the 1980s, for free.”

Jumblatt, whose father Kamal (a writer, philosopher, acolyte of Gandhi and also a “socialist” Druze leader) was murdered by armed men – almost certainly Syrian agents – in 1977, obviously enjoyed making his latest revelations with characteristic cynicism. “I said ‘yes’ without hesitating,” Jumblatt said of Ismailov’s request, “and we continued our endless lunch and I wonder how many bottles of vodka were consumed for this event – of course, for the cause of fighting ‘imperialism’ and for the sake of consolidating ‘socialism’.”

Two weeks later, Jumblatt continued, “came a man in his late fifties with his wife and we [later] accommodated them on the upper floor of the house of [Lebanese parliamentarian] Nehme Tohme … a great friend of the Jumblatt family. The Tohmes were and still are very hospitable. But who was this fellow and his wife? None less than Stig Bergling and Elisabeth Sandberg. And for the coming four years, he was our guest, and our partner at dinner or lunch.

“For the Soviets to ask me to hide one of their numerous spies was quite odd, and later my suspicions were confirmed that something was wrong in the Soviet Empire, because just after a year, it collapsed.

“Mr Abbe as we used to call him, Stig Bergling, fled Lebanon in 1994 back to Sweden, during my presence in Moscow at the time of Yeltsin, and he was jailed again … As for me, I ended up terribly embarrassed with my Swedish friends, the Social Democrats, with whom I was so closely connected, and thanks to this relationship I had the opportunity to meet several times a great figure and leader of the 20th century, Olof Palme. Stig Bergling did a lot of damage to Sweden and to me.”

Bergling had been parolled on health grounds after suffering from Parkinson’s disease and died on 24 January. His wife died of cancer 18 years ago.

His spying – solely for money, he made clear at his trial – supposedly cost Sweden $45m to reorganise its security operations. The Swedish justice minister resigned.

As for Jumblatt, he now describes the jovial and bespectacled spy as “an offer I could not refuse – the gift of General Vladimir Ismailov”. And since Jumblatt is one of Lebanon’s elder and most intellectual (and mischievous) statesmen, I can attest that he will never resign, at least until his son Taymour takes over the leadership of those most mountainous of men, the Druze.

Sisi’s calls for ‘rice’ to fund the army

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s judges go on sentencing his Muslim Brotherhood enemies to the gallows, but the Egyptian president is emerging as something of an amateur – for a former head of the army – when it comes to preventing leaks of his own phone calls.

This weekend, a Brotherhood radio station in Turkey broadcast what it claimed were conversations between the former field marshal and his aides after his military coup against elected Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi – but before he himself won the presidential poll. In one of the calls, dated to 2013, he reportedly tells his then chief of intelligence to ask for $10bn each from the Saudi, Emirati and Kuwaiti governments, adding that they “have money like rice, like the Americans”. He wants the funds transferred to an account belonging to the Egyptian army rather than the state.

“Rice” is an intriguing metaphor for cash. I’ve heard of dibs, dough, lolly, sugar, salt – and my thesaurus suggests “palm oil” as another. But I suppose rice comes in bags, is cheap to acquire and extremely filling, especially if you’re a poor Egyptian president trying to prop up your central bank.

And who could disagree with Sisi? After all, I imagine that the Islamic State is still receiving plenty of “rice” from the nations of the Gulf – or “half states” as the manager of Sisi’s office apparently calls them on one recording – although we must all repeat that the governments of Sisi’s favourite Arab funders would never support “terrorism”.

I should add that Sisi’s lads say the tapes are faked and “doctored” – they’re certainly hard to hear, because of the noise of all that Cairo traffic in the background.