The Beatles, protests with purpose, and optimism: why the Sixties were nothing short of a Golden Age

A confluence of economic and cultural wealth with political passion made the sainted decade a blessing for all those lucky enough to go through it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

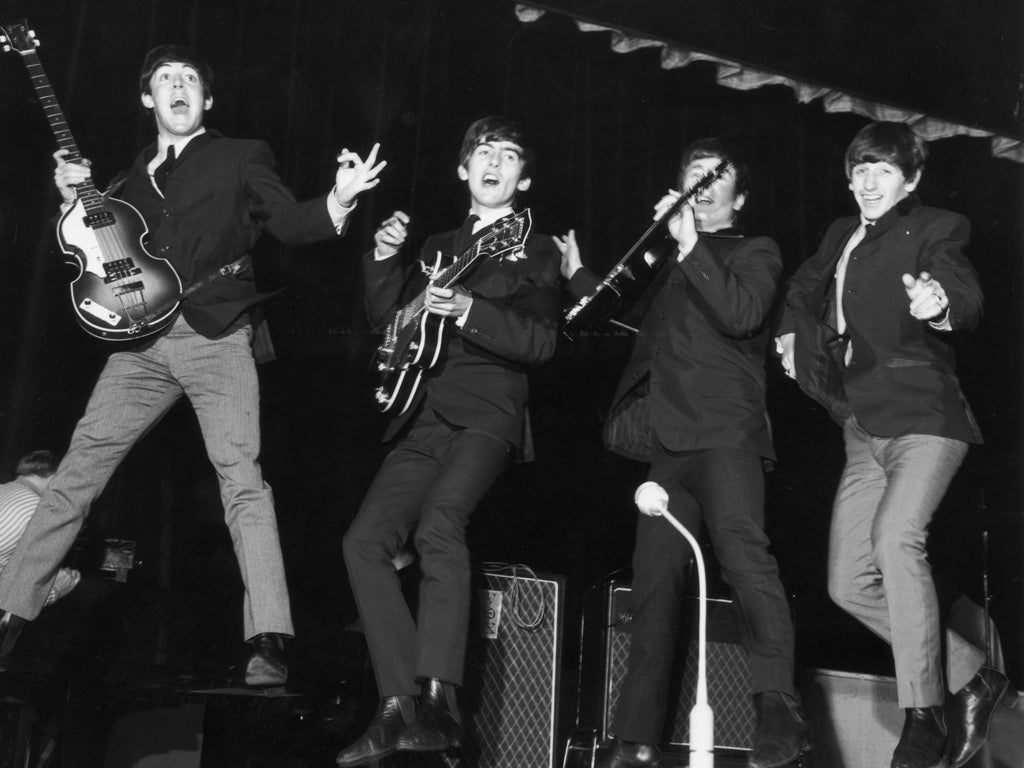

Your support makes all the difference.I almost missed the 50th anniversary of the day when the 1960s began, which of course was not 1 January 1960. I know because I was there. The mythic 1960s began with the release of the first Beatles song, “Love Me Do”, on 5 October 1962. Until then, or so it appears looking back, the country was still living through the rather dull era best described as post-war Britain.

Food rationing had ended in 1954, a fresh memory in 1960. Compulsory military service for young men was just coming to an end with the last conscript leaving the forces in May 1963. There was still a “season”, when the parents of the young ladies of the upper classes gave grand “coming out” balls for their daughters. Above all, the post-war era was deferential, whereas the 1960s proper were anything but, neither in music, nor in clothes, nor in waves of student protests. In each of these areas, the 1960s were exceptionally innovative.

Protest

The 1960s of legend were also an international phenomenon. Student protest movements had their greatest successes in France and the US in 1968. President de Gaulle found the pressure almost unbearable and resigned a year later. In the US, President Johnson prematurely ended his bid for re-election after a narrow squeak in the New Hampshire primary election. He said: “I felt I was being chased on all sides by a giant stampede… I was being forced over the edge by rioting blacks, demonstrating students, marching welfare mothers, squawking professors and hysterical reporters.”

Publication of the first Beatles’ song is as good an event as any to mark the start of the real 1960s because the Beatles seemed to reflect the big changes that were taking place in British society. Above all, personal freedom was expanding. Take as an example the introduction of the contraceptive pill. It was first developed in the United States during the mid 1950s as a method of regulating menstrual disorders. Only by chance was it found to serve as a reliable contraceptive. It arrived in Britain in 1961 and by the middle of the decade was in widespread use. It was arguably the most important social event of the entire 20th century. The contraceptive pill profoundly altered the balance of power between men and women. It allowed women to defer child-bearing, so giving them time to invest in education and careers, and was a factor in a large increase in female employment.

Education

At the same time, there was a big rise in the sheer numbers of young people. There were a million more unmarried 15- to 24-year-olds in the mid 1960s than 10 years before. They were better educated, financially better off and more independent than their predecessors.

Better educated because new universities were being founded at the rate of nearly one a year. Here is the astonishing chronology – University of Exeter (1955), Leicester (1957), Sussex (1961), Keele (1962), East Anglia (1963), York (1963), Newcastle (1963), Strathclyde (1964) and Lancaster (1964) – nine new universities in 10 years and then, almost unbelievably, an acceleration. A further 14 were to be launched by the end of 1967, starting with Kent and ending with Stirling.

But these universities and some of the older ones, leaving aside Oxford and Cambridge, were not just academic establishments. For their campuses and their indoor and outdoor spaces lent themselves to meetings and debates and even to organising mini demonstrations. These students’ intellectual gods were Marx, Freud and Sartre, the French existentialist philosopher. In a famous passage, Sartre wrote that “God does not exist, and as a result man is forlorn, because neither within himself nor without does he find anything to cling to”. This struck home. For as Bob Dylan sang in 1965 – “How does it feel/ How does it feel/ To be on your own/ With no direction home/ Like a complete unknown/Like a rolling stone?”

Optimism

So one had either to start things on one’s own without adult backing, or not at all. This was an unprecedented and intoxicating freedom. As the French student leader Dany Cohn-Bendit told the Paris demonstrators in May 1968: “There are no marshals and leaders today. Nobody is responsible for you. You are responsible for yourselves.”

Or as an advertisement for the American Democratic politician Eugene McCarthy – who unhorsed President Johnson in New Hampshire – proclaimed to his young followers: “We are the volunteers, and the mercenaries are no match for us. We are the contributors of 10 and 20 dollar bills, and together we are bigger than big money. We are the asphalt, and we are conquering the steam roller.”

The enduring characteristic of people who lived through the 1960s as young adults is that they have remained optimistic and never lost their belief that anything is possible. In their twenties, they could have worried about the nuclear bomb, or the Cold War, but most did not. Jobs were plentiful, inflation was low and house prices were affordable. What was not to like? It was a golden age and those of us who were there at the time were very lucky indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments