Seduced by the fedora, turned off by the trilby – a man’s hat can tell you a lot about his art

Famous hat-wearers, the painter L S Lowry and the singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen might seem strange bedfellows, but it's what's under that tifter that really counts

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

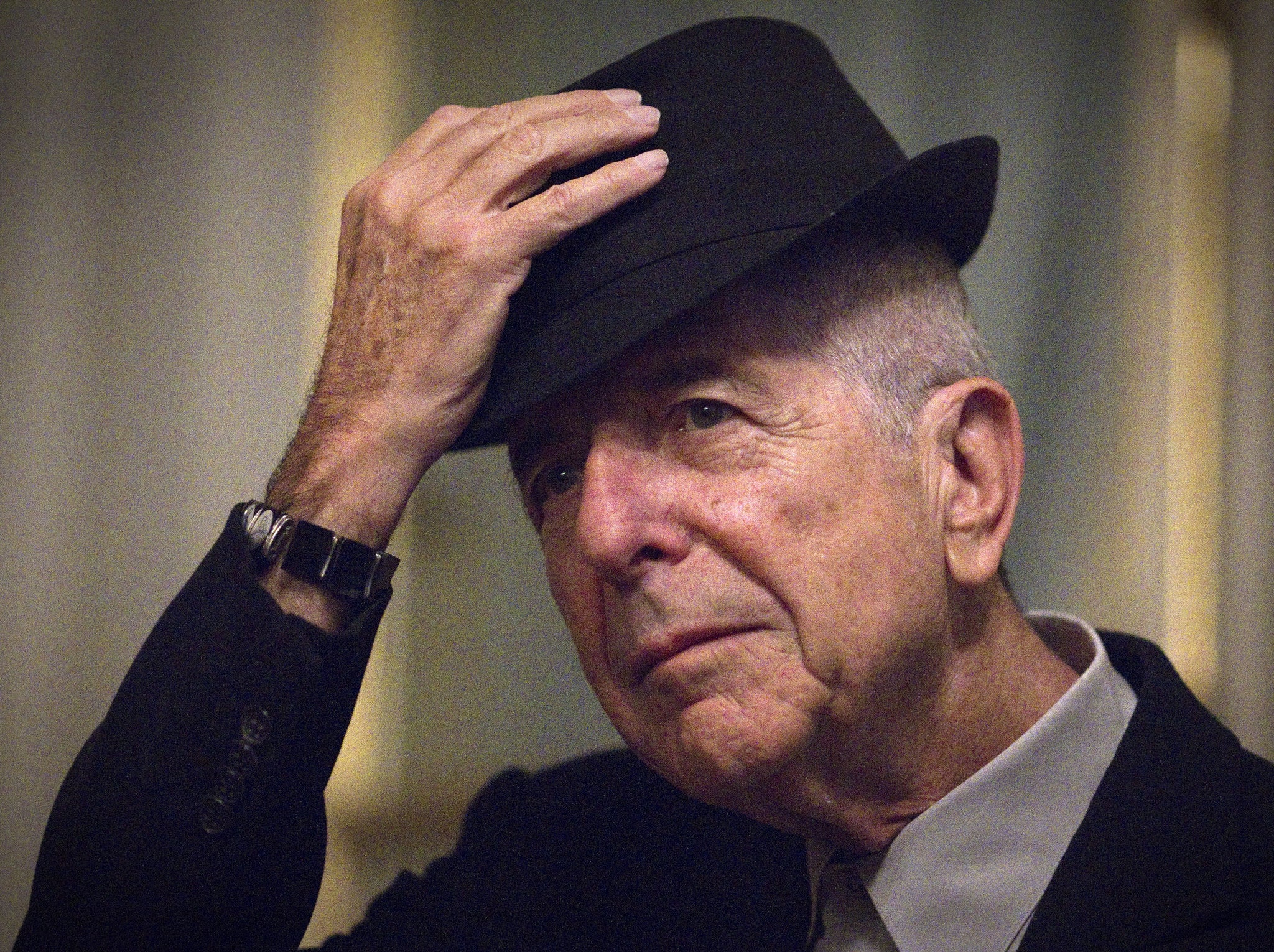

Your support makes all the difference.Today: two lessons in how to wear a hat. My exemplars are the painter L S Lowry and the singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen. Dr Johnson said of the metaphysical poets that in them “the most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together”. We don’t hold with violence in this column, nor do we mean to court the cheap controversy of heterogeneity. Lowry and Cohen might, on the face of it, make strange bedfellows, but both took London by storm last week – Cohen at the O2 Arena, Lowry at Tate Britain – and both define themselves by the way they wear a hat.

Leonard Cohen’s hat is well known. You’ll find sites on the internet in which aficionados of the singer’s wardrobe go head to head, as it were, on the question of whether what he wears is a trilby or a fedora. To the literalists it comes down to the size of the brim and the nature of the crease at the crown, but I am of the party that thinks it’s how you wear it that determines what it is. If you are possessed of cool, you will turn a trilby into a fedora. Let’s face it, if you are cool, you will turn a knotted handkerchief into a fedora. And Cohen is nothing if not cool. Amazing that one can look cool at 79, but if he knows how to wear a hat, then a hat knows how to wear him, and a good one can take years off you.

Cool is not a word even his most devoted admirers would use of Lowry. But a giant blown‑up photograph of him in a capacious raincoat and a hat that is closer to a pudding than a fedora greets you at the entrance to the Tate show, and there can be no doubt that the hat is a statement of creative intent. Just so you know where I stand, I saw Cohen and Lowry last week, and while I had a good time with Cohen, I had an even better one with Lowry. Make no mistake, this is a magnificent – magnificently conceived and curated – exhibition. You could quibble about the paintings that aren’t there – the portraits, the seascapes and landscapes, the late, strange, corseted women – and you could take issue with the Marxist emphasis on him as a critic of industrialism. But to complain of anything is churlish given that it’s little short of miraculous that the Tate should have granted so unfashionable (and unfashionably popular) a painter an exhibition at all, given its scale, and given how convincingly, room by room, painting by painting, it makes the case for his genius. Visionary genius, I would say, allowing that you can be a visionary of godlessness, a seer of desolate, whited-out infinities – but that’s a matter for another day.

If there was a revivalist atmosphere at the Leonard Cohen concert – people singing along to songs they first heard before their now middle-aged children were born – there was a triumphalist feeling at the Lowry exhibition, where obscure enthusiasts and well-known collectors congratulated one another simply on seeing what they had never thought they’d live to see. “We did it!” someone who’d been buying Lowrys all his life and didn’t own a single painting by anybody else told me, as though he – he and I – had finally come in from the cold. The difference between our enthusiasm and that of Cohen’s fans was that while we loved our man’s work as much as they loved theirs, we didn’t want to be him. Who wants to be a man that wears a hat like that? Whereas to wear a fedora like Cohen...

I sat next to a Cohen lookalike at the O2 Arena. Not as aged or as switchblade lean, but wearing his hat identically and given to ironic, deep-throated mumblings. He knew every song by heart, and appeared, at times, as though he had passed over into another reality. Cohen sang what was in my neighbour’s soul. I won’t say everybody at the concert was transported to this degree, but most were. It was like being at a very sedate, elderly orgy. “Dance me to the end of love,” Cohen sang, and that was precisely where he took us – to love’s very extremities. Cohen’s peculiar genius is to have made masochism melodic, and by that means to have turned it into macho. Song after song celebrates erotic surrender. Fine by the man next to me. He yielded up his being. Fine by all the other 70,000 fetishists in the stadium. Sexually speaking, probably the sweetest, least aggressive people on the planet. But the question has to be asked whether art is best served by submitting yourself to it so completely. Can it even be said to be art that you’re enjoying when what you are is seduced?

The hat gives the game away. Love me under my fedora, Cohen asks. Ignore me, says Lowry under his shapeless trilby – for I am unlovable – and look instead at what I make. Very Manchester, this unwillingness to whisper sweet nothings. We are plain-speaking, sarcastic, self-denigrating, difficult buggers up there. We’ll meet anyone halfway, provided they are plain-speaking, difficult buggers too. For years, it seems to me, it was Lowry’s refusal to talk up his work, to give his paintings other than bog-standard titles, to aggrandise, to woo, to seduce us with the charm of paint or the allure of sentiment that kept him out of the mainstream.

Paradoxically, this reluctance to be idolised should have recommended Lowry to the sternest of contemporary critics – those aestheticians who, after Adorno and Laura Mulvey, cautioned against “libidinous engagement with the art object”. “Passionate detachment” was what they preached instead. Precious chance of that when the artist tips his fedora at you. Lowry’s charmless titfer, on the other hand, keeps us strictly in our place.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments