Ronnie Biggs: It was our romantic attachment to crime that turned the Great Train Robber into a star

He assumed the mantle of the rogue with no regrets

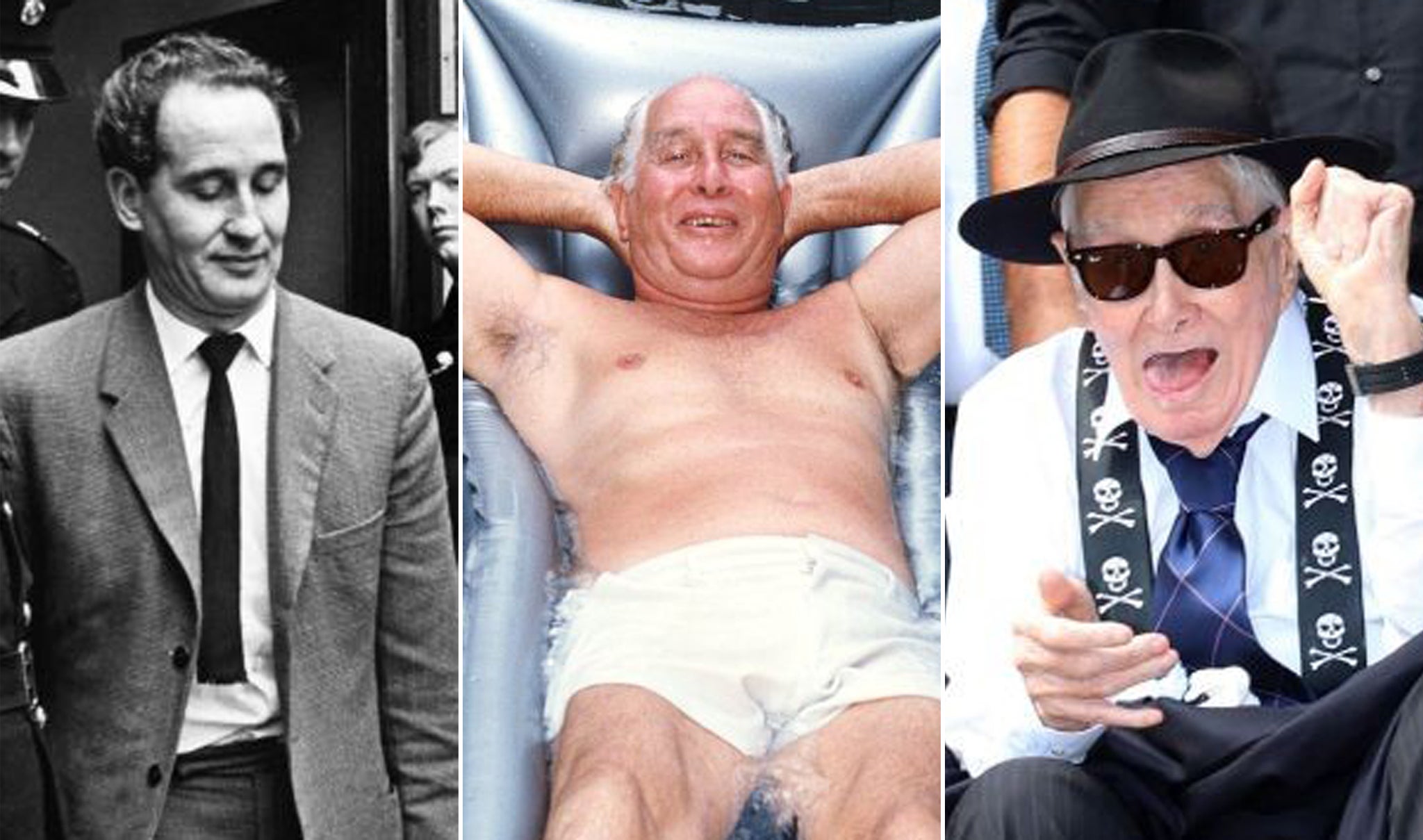

Ronnie Biggs, the great train robber who has died aged 84, was a small-time criminal transformed into a notorious monster/celebrity (take your pick) by forces beyond his own making or control. That he emerged as he did – as a survivor of a criminal world long since reduced to a branch of entertainment: turn on the telly any night – was entirely due to the romance with crime and criminals with which even the law-abiding have long been besotted.

This is not an apology for Biggs or his fellow conspirators, rather an explanation. Biggs had other options than to become a criminal, yet he was a thief as a teenager and was dishonourably discharged from National Service for breaking into a chemist’s shop. In the late ‘50s and early ‘60s there was a criminal culture into which he easily slipped. He was a village footballer, as it were, who found himself – thanks to his role in the Great Train Robbery – a centre-forward in the World Cup.

Once liberated (by his 1965 break-out from Wandsworth Prison and by his propulsion into the world of 24-hour news), Biggs took full advantage of his infamy and assumed the mantle of the rogue with no regrets. Had he and his 16 fellow robbers stopped the “wrong” train that night in 1963 and come away with bags of coal rather than with £2.4m (£45m in today’s values), a sum that stunned the gang as much as it did the public, he would now be going to a south London grave quietly and without fanfare.

For the crime was indeed the money. Mr Justice Edmund Davies, who handed down 30 year terms to the robbers, stressed their “greed” – surely the sine qua non of all robberies. The gang hit and concussed the train driver, Jack Mills, whose bandaged head became an enduring image. Those who felt that the sentences were excessive could point to regular robberies of similar brutality that profited criminals little and drew far shorter jail terms.

There is a chasm in British criminal justice between the majority who believe that courts and prisons exist to punish (the day the train robbers were sentenced – then 30 years was exceptional – a man I knew muttered: “They should have thrown away the key”), and those who believe that the aim should be to rehabilitate. The opposition to votes for prisoners shows where the majority (and most politicians) stand. Biggs lived on the fault line (and in the spotlight) between these two opposing views of criminal justice.

In 1963 Biggs’s imagination scarcely extended as far as Calais, never mind Australia and Brazil, where he lived most of his life on the run. But, finding himself on the most wanted list and in possession of a small fortune (each robber received £147,000: today’s equivalent is £2.6m), the world perforce became his oyster – first Spain and Australia and then famously Brazil, where his paternity of a Brazilian child offered him legal sanctuary.

Although Biggs embraced both life on Copacabana Beach and the fame/opprobrium he enjoyed, once Fleet Street had tracked him down, in his heart he carried a fading mid-20th century picture of England. In an interview in Brazil, he spoke of the “green grass of home”. When he returned 12 years ago, it was of his own volition.

The man once quick on his feet (in all senses) was a wreck. I saw him shuffle into a visitors’ room at Belmarsh Prison, a decrepit pensioner who had suffered strokes. Many saw little point in further confining Biggs, but Jack Straw, then Justice Secretary, ruled that Biggs should not be released because he was “unrepentant”, adding that he had committed a further crime by escaping.

When he was finally released in 2009, on the grounds that he was at death’s door, he infuriated many who believed he should complete his full time by lingering among us for another four years. Last seen in public at the funeral of fellow train robber Bruce Reynolds, Biggs was a sad sight. From his wheelchair he raised two shaky fingers at the cameras and at the world beyond.

Biggs will be mourned by few, but with his death has gone a high-profile symbol of a vanished criminal era that diverted many.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments