Richard Haass’s talks will not have failed if Britain accepts it must now get real on Northern Ireland

The Good Friday Agreement was not a prelude to greater integration

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

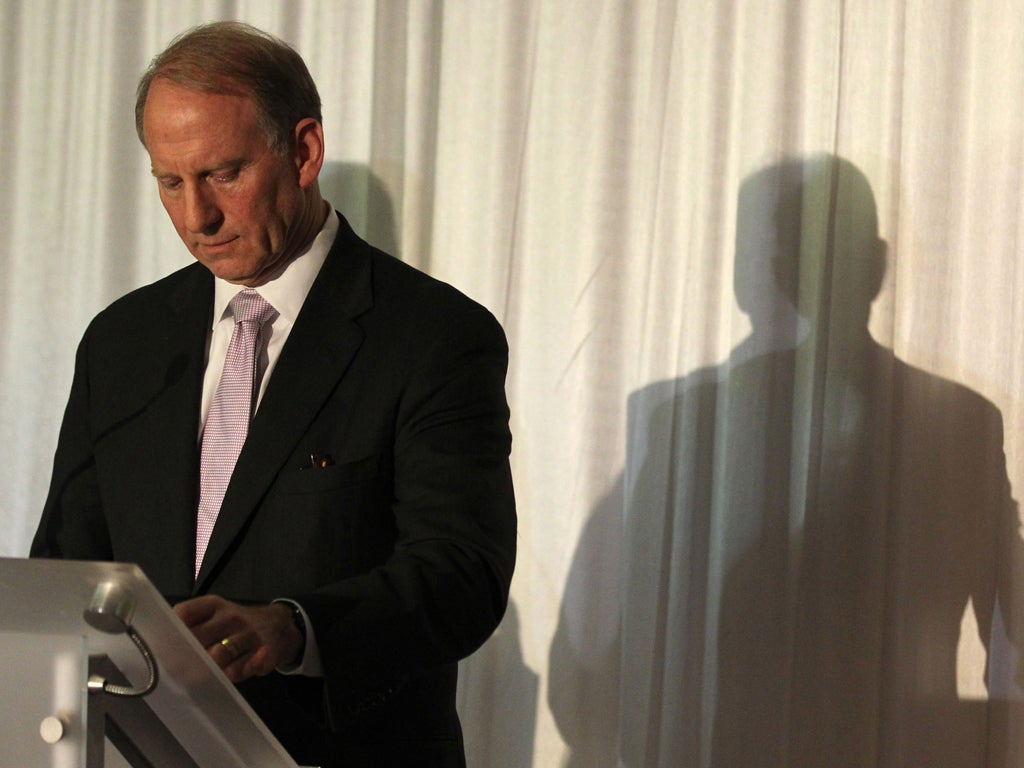

Your support makes all the difference.So common a negotiating ploy has late-night brinkmanship become – what with EU summits and the recent Geneva talks with Iran – that it was almost refreshing to wake up to the news that the talks on Northern Ireland had failed. By the time dawn broke on Tuesday, the joint negotiator, Richard Haass, was on his way back to the United States; job not done.

Failure, in fact, was a word the parties to the talks eschewed, even denied, and public recriminations were minimal, which many hailed as a positive sign, leaving open the prospect of later success. I would rather describe this response as the latest instance of official Britain’s continuing self-deception over Northern Ireland, and a refusal to face facts that has done no one any good.

The first piece of wishful thinking, I regret to say, concerns Dr Haass. He has the air of a reasonable and decent man, but – contrary to what has been said, especially on this side of the Atlantic – he does not have a stellar record as a negotiator, or even much of a record in this area at all. He is an American academic and policy adviser. He is no George Mitchell, a shrewd and wily lawyer who commands top fees for a reason. Still less is he a Richard Holbrooke, who could be a bruiser when he chose. That so many felt the need to puff up Dr Haass’s reputation shows he was probably not the right choice in the first place.

This is not to underestimate the task facing Dr Haass and his co-negotiator, Professor Meghan O’Sullivan. (Let’s not forget there were two.) The phrase, “parades, flags and the past”, trips easily off the tongue, but that, too, is deceptive. Each element is a profound reflection of such basics as identity, power and sovereignty. Together they constitute the nub of the continuing conflict in Northern Ireland. There is an unresolved contest for power, which is played out in every parade, symbolised in every flag and barely buried in every graveyard.

None of these aspects can be trivialised. When, in December 2012, Belfast City Council voted to fly the Union flag on only 18 days a year, everyone in Northern Ireland understood what that signified. It was visual proof that Unionist power was waning; a defeat for one side and victory for the other. From London, where – thanks to Gordon Brown – Union flags now fly routinely from every government building, it was easy to scoff at the fuss. But flags are part of the currency of power; you change the arrangements at your peril.

And the third piece of wishful thinking, or perhaps worse, has been the overselling of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. Tony Blair and his advisers of the time have made whole new – and lucrative – careers, trading on the success of that agreement as a template for resolving divisions everywhere.

Peace, of course, however uneasy, is infinitely preferable to war. And the boldness of the leaders on both sides who took the decision to lay down arms and share power deserved all the praise they received. Even with the sporadic attacks that take place now, Northern Ireland is a far better place to live than it was for the 30 years or so of what – in another euphemism – are disingenuously termed The Troubles.

But an accommodation that stopped most of the killing was not, as many on the Mainland hoped, a prelude either to greater integration or to reconciliation. Residential segregation according to religion is as complete as it ever was, now reinforced by walls. Most education remains separate – so the difficulty in agreeing on any joint scrutiny of the past is likely to continue. In the UK, there has always been a tendency to see Northern Ireland as a special case. But this is only true in so far as everywhere has its unique geographical and social character. In the nature of its dilemmas, Northern Ireland is little different from the many other – often small – parts of the world where power is contested, and those who once enjoyed privilege find it seeping away.

The reasons may reflect changing demography, the consequences of a war, or the decline of a colonial power. Think the Serbs in Kosovo, the Sunnis in Iraq, the Alawites in Syria, the Afrikaner in South Africa. Splitting territory is one remedy, which is how Northern Ireland came into being. Guaranteed equal rights for all is another, which is what the Good Friday Agreement enshrined. But these do not by themselves solve the “parades, flags and the past” problem, where culture, dignity and power are all at stake. So ingrained are these differences that they may simply have to be tolerated until the rising power definitively gains the upper hand or there is common consent to a new beginning – which could be many years away.

Had the Good Friday Agreement not been so oversold, the definition of success might have been more limited and expectations for the immediate future more realistic. If it is now recognised that reconciliation is a whole lot more difficult than peace – in Northern Ireland, as elsewhere – this week’s failure may have been of some use.

Truth trapped in the ice

There is much to enjoy about the tale of the good ship Akademik Shokalsky, not least the news – relayed breathlessly from Antarctica yesterday – that the scientists, journalists and tourists aboard, were airlifted from the icy wastes to the safety of an Australian vessel, from a helipad they had trampled into being themselves. This, despite – as I understood from a previous report – supplies that would have lasted until March.

Yet, I must admit to some befuddlement. In the early days, I could not understand why a BBC reporter was aboard a Russian ship in the Antarctic. Had he been among the unlucky tourists? Then it transpired the ship had been chartered, but by whom, and why, was a mystery. A few more days in, I learnt this was a voyage to mark the centenary of a journey made by the explorer Douglas Mawson, and that the purpose was also scientific.

Now, maybe I was unlucky in the reports I caught. But it was even later that I grasped the climate change angle. Oh joy, the marooned scientists were hoping to measure a century of ice depletion; instead, they were trapped in the stuff, at the height of the southern summer!

No wonder climate sceptics have been cock-a-hoop; no wonder an old Antarctic hand told the BBC that measuring sea ice was complicated. I’m sure it is. It would just have been nice if the truth had not had to trickle out. Perhaps, like the scientists, it was hoping for a thaw.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments