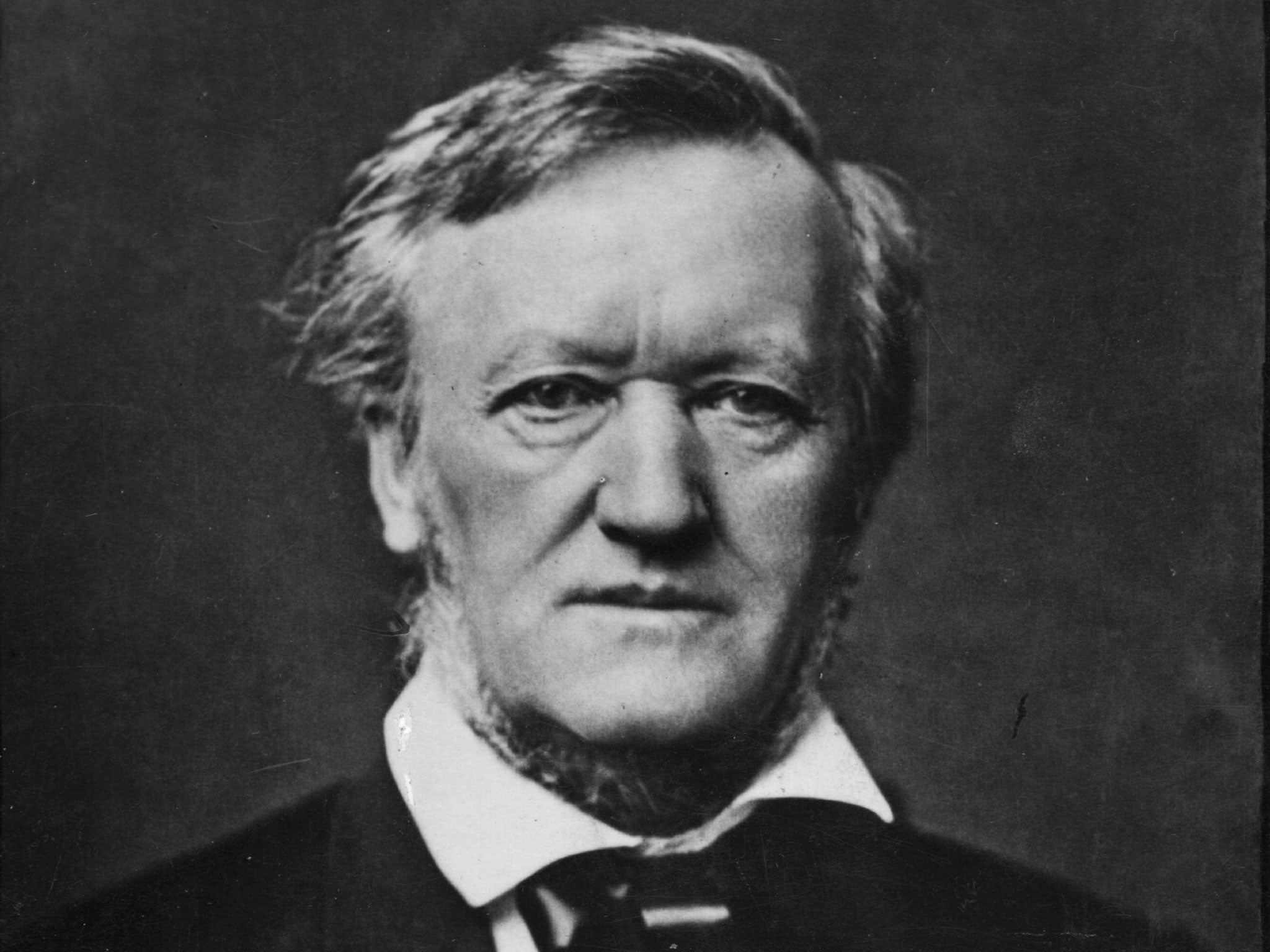

On the 200th anniversary of Wagner's birth, let's learn to love the music - yet still hate the man

Hitler’s favourite composer was a monster, but he should still be celebrated

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Next week there will be a special concert in London honouring a man who wrote an infamous anti-Semitic tract “Das Judenthum in der Musik”, and whose own musical theatre was acclaimed by Adolf Hitler as the earliest inspiration for his idea of a pure German master race. That man, of course, is Richard Wagner, and next week’s 200th anniversary of his birth has occasioned many more celebratory concerts and festivals in the land of his birth.

It has provoked controversy there, too: last week a Dusseldorf production of Wagner’s 1845 opera Tannhauser, but with sets based on Nazi concentration camps, was cancelled after its premiere. The scenes were apparently so realistic – in terms of the horror of the gas chambers – that some of the audience needed medical assistance to recover. As the musicologist Norman Lebrecht observed, it was a rather bizarre interpretation, anyway: Tannhauser is set in the Middle Ages and involves Wagner’s usual preoccupations with sacred and profane love.

Yet the intention of the director, Burkhard Kosminski, was simple enough to understand. In the month of Wagner’s bicentenary, he wanted to link the music to the events which the composer’s own ideological views seemed to presage: in “Das Judenthum in der Musik”, Wagner had compared the Jewish influence on music with maggots feasting on a diseased or dying body, and called for it to be extirpated by “a bloody struggle of self-annihilation”. And last month an essay in the German magazine Spiegel on “Wagner’s Dark Shadow” revealed a letter Wagner wrote to his wife Cosima, after she had told him how a fire in a Vienna theatre, during a performance of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s Nathan the Wise, had killed hundreds, about half of them Jews; Wagner replied: “All Jews should burn to death in a performance of Nathan.”

Nice man. Yet whatever his character, or his views – and whatever formative influence those views may or may not have had on the mind of Adolf Hitler – it is right to celebrate his anniversary. His music is sublime; manipulative in the way it plays upon our emotions, certainly – as Daniel Barenboim among others has pointed out – but then all great music works by somehow tapping in to our subconscious, rather than appealing to our rational selves.

Barenboim himself has waged a lonely struggle to introduce the music of Wagner to the concert halls of Israel. The conductor makes the simple point that while Wagner himself was a vile anti-Semite, “his music isn’t anti-Semitic” and “as a musician, you simply can’t ignore him”. Others have quibbled with this, arguing that certain of the characters in some of Wagner’s operas conform to anti-Semitic stereotypes; but Barenboim is right – the music itself is no more anti-Semitic than it could be described as right-wing or left-wing. The arrangement of musical notes is an aesthetic phenomenon, entirely divorced from the world of politics, and, indeed morality. Those who would ban Wagner’s music on such grounds are no different from the Stalinists of the Soviet Union, or the commissars of China’s cultural revolution, who sought to make the composition of music a slave to political ideology; indeed, they are even dangerously close to Hitler’s own views on the role of culture.

In a way, this sort of delusion is understandable. Because man cares so much about music, because it resonates so deeply with us, those whose compositions we admire are described as “role models”. This explains why rock stars are so frequently importuned by politicians to support their campaigns – and indeed, some musicians, such as Bob Geldof or Bono, use their unique status as musicians to promote their own political objectives. But there is no valid connection, whatever, between the inner abstract world of music and the outer world of things and political parties, even if at times each exploits the other.

It is true that some of the ancients, such as Plato, saw music as an indicator of morality; and in our own time the philosopher Roger Scruton has advanced similar ideas. Obviously, we can talk about good and bad music, at least to the extent of saying, for example, that JS Bach, was a “better” composer than any of his children who followed in the family business. But when we talk about a “bad” piece of music, we never use the word in the moral sense; we only mean that it doesn’t work well, as an arrangement of notes and harmonies – and even that is necessarily subjective.

Scruton, a conscientious Christian, argues that “moral virtues and vices” are present in music, but this seems very misguided. To take the basic Christian notion of sin, for example: can any piece of music be described as “jealous” or “envious” or “covetous”? Its composer might be, but that is a completely different proposition.

We can be quite precise about this distinction. That wonderful composer Richard Strauss, appointed by Josef Goebbels to the presidency of the Reichsmusikkammer in 1933, wrote a song in gratitude. It ends with the peroration: “He, I believe, will be my leader.” The “he” – for the avoidance of any misunderstanding – was meant by Strauss to refer to Adolf Hitler. Michael Kennedy, Richard Strauss’s pre-eminent biographer, and a man of deep musical sensibilities (as well as one who fought in the Second World War), describes this song as “musically delightful”.

Or take the case of Richard Strauss’s contemporary, Wilhelm Furtwangler: I am hardly unusual as regarding this conductor’s interpretations of Beethoven’s symphonies as unmatched. Possibly the greatest performance he ever directed of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony was in Berlin in March 1942, in a concert marking the Fuhrer’s birthday. One critic has described this performance as “diabolical… demonic” and its conclusion as “one of the most profoundly horrifying sounds ever recorded”.

Well, you can see it for yourself: it was filmed by the Nazis, for broadcast, and is available in full on YouTube. It is indeed hard to watch as the camera pans to Josef Goebbels and sundry other acolytes of Hitler, in rapt atttention, against a background of a hall festooned with giant swastikas. But then play it again, with your eyes shut, just listening to Furtwangler’s performance with the Berlin Philharmonic. It is astounding, uplifting, inspirational. It is beyond good and evil – like Wagner’s greatest music.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments