Now the economy is finally recovering, 2015 could well be the year of the left

A new study gives hope to progressives who have been disheartened by a shift to the right in recent years

2015 will be a key election year across the world, with many countries holding legislative and presidential ballots. One key trend to watch for will be a potential pick-up in performance of parties of the left and centre-left, which have generally failed to capitalise electorally on the most acute period of economic crisis since the 1930s.

In the two years after 2008/09 alone, for instance, parties of the left and centre-left lost ground in countries as wide-ranging as Australia and New Zealand, the Czech Republic, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, the US and the UK.

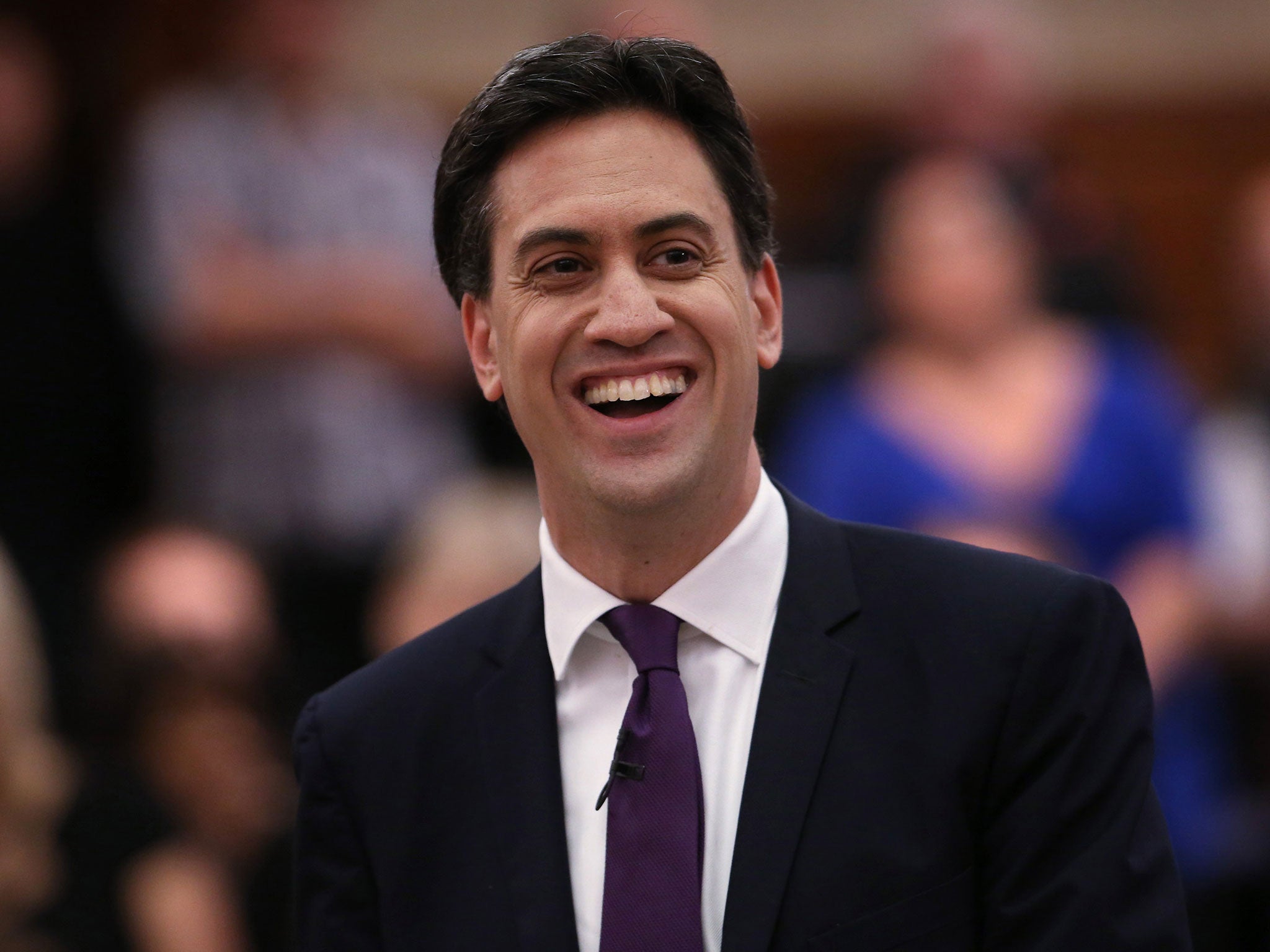

But the fortunes of these and similar parties may now be on the turn, spearheaded by a new generation of politicians. After almost a decade of Conservative rule in Canada, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau, the son of former long-serving prime minister Pierre Trudeau, is championing a narrative of the struggling middle class in advance of the 2015 ballot. He's enjoyed a poll lead for much of the period since he became leader of the opposition in 2013. And of course, here in the UK Ed Miliband hopes to win office in May on a platform of voter discontent over stagnant living standards, and his party has led most opinion surveys since 2011 (although the gap is becoming increasingly narrow).

While Trudeau and Miliband are championing centre-left platforms, more radical left-wing parties may also be on the cusp of power too. In Greece, Alex Tsipras, 43, the leader of Syriza (the coalition of the radical left) could become prime minister as soon as January 25.

He has campaigned on an anti-austerity mantle that could see the country leave the Eurozone. He has promised an end to “the regime that sank the country into poverty, unemployment, grief and desperation”, that has seen the economy shrink by over a fifth since 2008.

Meanwhile, Spain's right-wing People’s Party faces a complicated re-election battle in Autumn 2015, due to a challenge from the insurgent left-wing party Podemos (“We Can”).

Podemos was founded in 2014 by Pablo Inglesia Turrión, in response to the festering social crisis in the country following economic turmoil in recent years which has, for instance, seen youth unemployment rise to almost 60 per cent. Despite being such a "young" party it has led numerous national polls in recent months.

While the ascendancy of Podemos in Spain in the last year is especially striking, economic inequality is a salient issue across much of the globe right now. And it's not just politicians, but also other prominent figures, including Pope Francis, who are championing progressive agendas.

Professor Johannes Lindvall's research on the political consequences of the 1930s Great Depression, and the post-2008 "Great Recession", is illuminating about the left's prospects. What it shows is that parties on the right generally perform stronger in ballots soon after an economic crisis. According to Lindvall, this can be explained by the number of middle class voters who cast their lot in with conservative parties, as they've always been seen as better positioned to tackle financial crises.

However, Lindvall found that once the Great Depression was no longer seen by voters as a continuing threat, the political pendulum tended to swing back toward parties of the left and centre left.

Although, of course, history doesn't always repeat itself. Lindvall notes that politicians of the left and centre left today have less new agenda setting ideas and policy options than in the 1930s, when an era of expansionary fiscal policies and welfare programmes blossomed.

Today, leaders on the left still haven't developed coherent or persuasive responses to the economic downturn of recent years, nor the growing salience among many national electorates of a range of other issues, including immigration.

Nonetheless, history shows that income and status differences can be a powerful source of appeal to the disaffected. And the longer the legacy of the post-2008 crisis prevails (in the form of stagnant living standards, say), there could be much greater electoral opportunities for the left.

Just like the 1930s, economic hardship is now being felt in many countries not just by the poor, but also middle classes. And, it is this discontent that politicians of the left will seek to tap into in coming months to win power against conservative incumbents.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments