Novel translation lets us know what is really happening in the world

Britons are now listening to what's happening outside of their borders with keener ears than ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As he previewed David Cameron’s meeting with Jean-Claude Juncker, the BBC journalist turned automatically to a handy metaphor. These were, he explained, very early days in the long process of EU renegotiation. In effect, the Chequers discussion represented no more than “the opening overs” in a five-day Test match. Come again, señor?

Those millions of Britons who refuse to learn any other language always console themselves with a favourite fantasy. The British, they believe, speak the world’s chosen tongue as their birthright. They have won the lottery of globalised life. In fact, they grow up speaking a rich, resourceful but ever-more parochial provincial dialect.

Every year, it has less and less in common with the pared-down and context-free “globish” in which much of the planet does its cross-border business. Try banging on about opening overs and sticky wickets at that crucial bid for a contract in Kuwait against Koreans and Brazilians.

Given the triumph of “globish”, language-learning will become not less but more important for the British. Yet the stubborn monoglots still rule. The myth of an English-speaking planet that hands out free passes to those who claim the language as a mother tongue has reinforced an assumption of superiority that took root in the age of empire.

However, ritual denunciations of the dire state of language teaching or the laziness of Brits abroad should not overlook the diversity on our doorstep. The real Britain has a wonderfully complex linguistic landscape, enriched by waves of migration, with scores of tongues alive within its borders. Official Britain, though, still depends overwhelmingly on its interpreters.

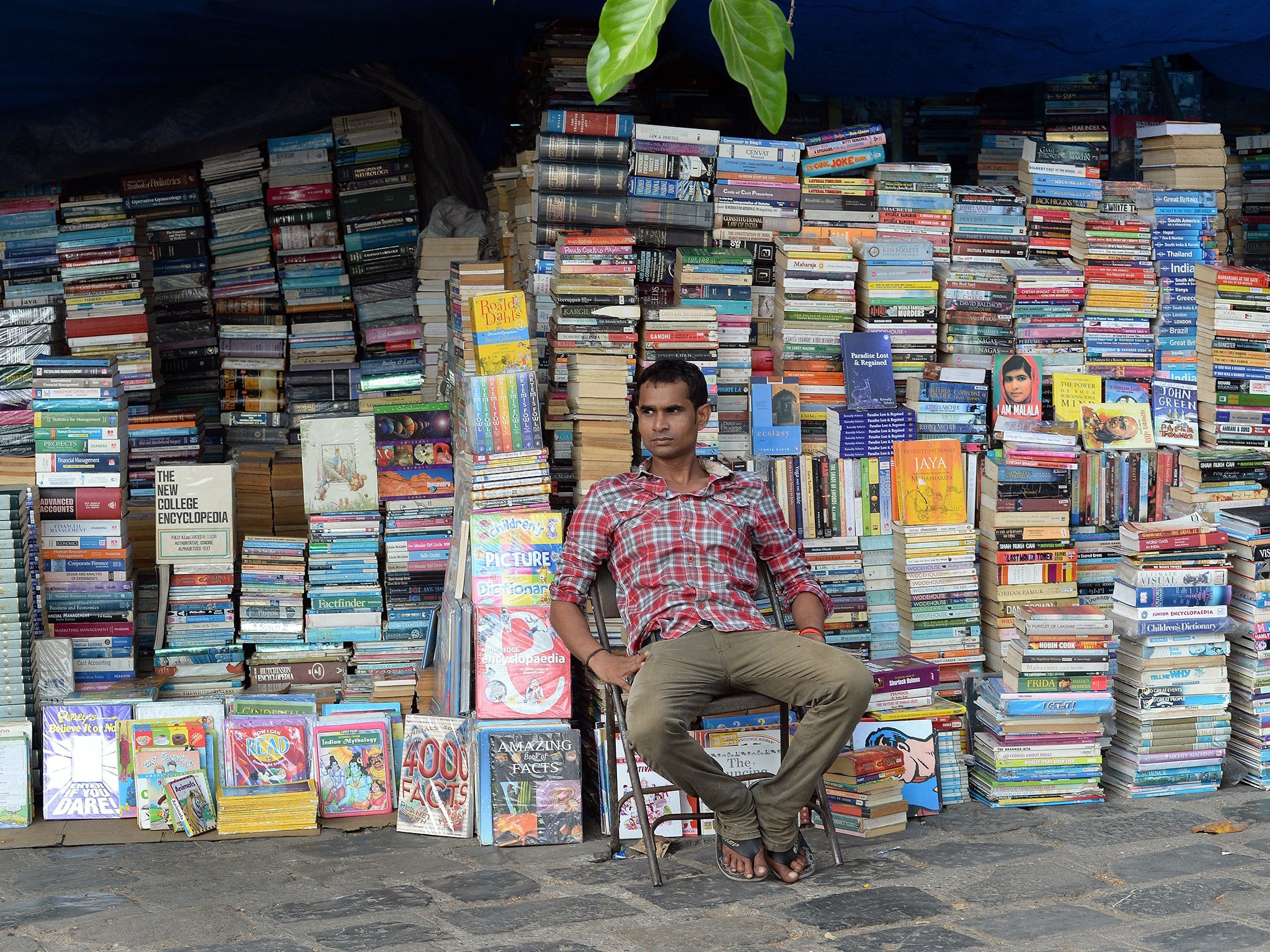

For as long as that remains the case, we can at least honour and reward the arts of translation that deliver the world to our doorstep. On Wednesday, the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize will be awarded again.

This newspaper pioneered an award for contemporary literature in translation in 1990. The first winner was Orhan Pamuk, long before the Nobel Prize committee saluted the Turkish novelist’s work. Since its revival in 2001, the Independent prize has run in partnership with Arts Council England and Book Trust, always with the aim of celebrating both the finest global fiction and the precious skills of the translators who let us enjoy it.

Last year, the IFFP hailed its first Arabic winner: the exiled Iraqi author Hassan Blasim. Along with his translator Jonathan Wright, Blasim took the award for his wildly imaginative stories of life in his ravaged homeland, The Iraqi Christ.

This year, we have a formidable shortlist of six novelists divided between Europe – Erwin Mortier from Belgium, Daniel Kehlmann and Jenny Erpenbeck from Germany – and the wider world: Haruki Murakami from Japan, Tomas Gonzalez from Colombia, Juan Tomas Avila Laurel from Equatorial Guinea.

It may seem a long way from tetchy EU wrangles in the Chilterns to the subtleties and nuances of literary translation. Yet if Britain is still a nation where impenitent monoglots call the shots, that creates a paradox. In politics and culture, it makes us more dependent on a corps of language experts in order to understand how others think and feel. If many of us won’t learn other tongues, we can in any case cherish and applaud the art of the interpreters who rescue us from the loneliness of the “anglosphere”.

Beyond the year-on-year impact of the Independent prize, other signs indicate a growing willingness to hear voices from elsewhere. After a run of English-language winners, last week the biennial Man Booker International Prize went to the mesmeric Hungarian novelist Laszlo Krasznahorkai.

In the UK, the proportion of literary fiction published in translation has crept up from the oft-quoted 3 per cent to something nearer 5 per cent. Since the entire output of British publishers has expanded crazily, that modest growth hides the good news that total numbers of translations have expanded by almost two-thirds.

Those figures could, and should, grow even further. But at a time when UK foreign policy and the response to it often sounds like a dialogue of the deaf, the quiet advance of the culture of translation shows that many Britons listen to the world with keener ears than ever.

That attentiveness will deepen whether the opening overs at Chequers eventually lead to an innings victory or a humiliating follow-on (translation available upon request...)

Boyd Tonkin will be interviewing the winner of the 2015 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize at the Hay Festival on Thursday 28 May: hayfestival.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments