Nietzsche's ideas might have been dangerous, but that's no reason to ban a club dedicated to the man

Once we start censoring one ideology then we may as well censor all of them

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

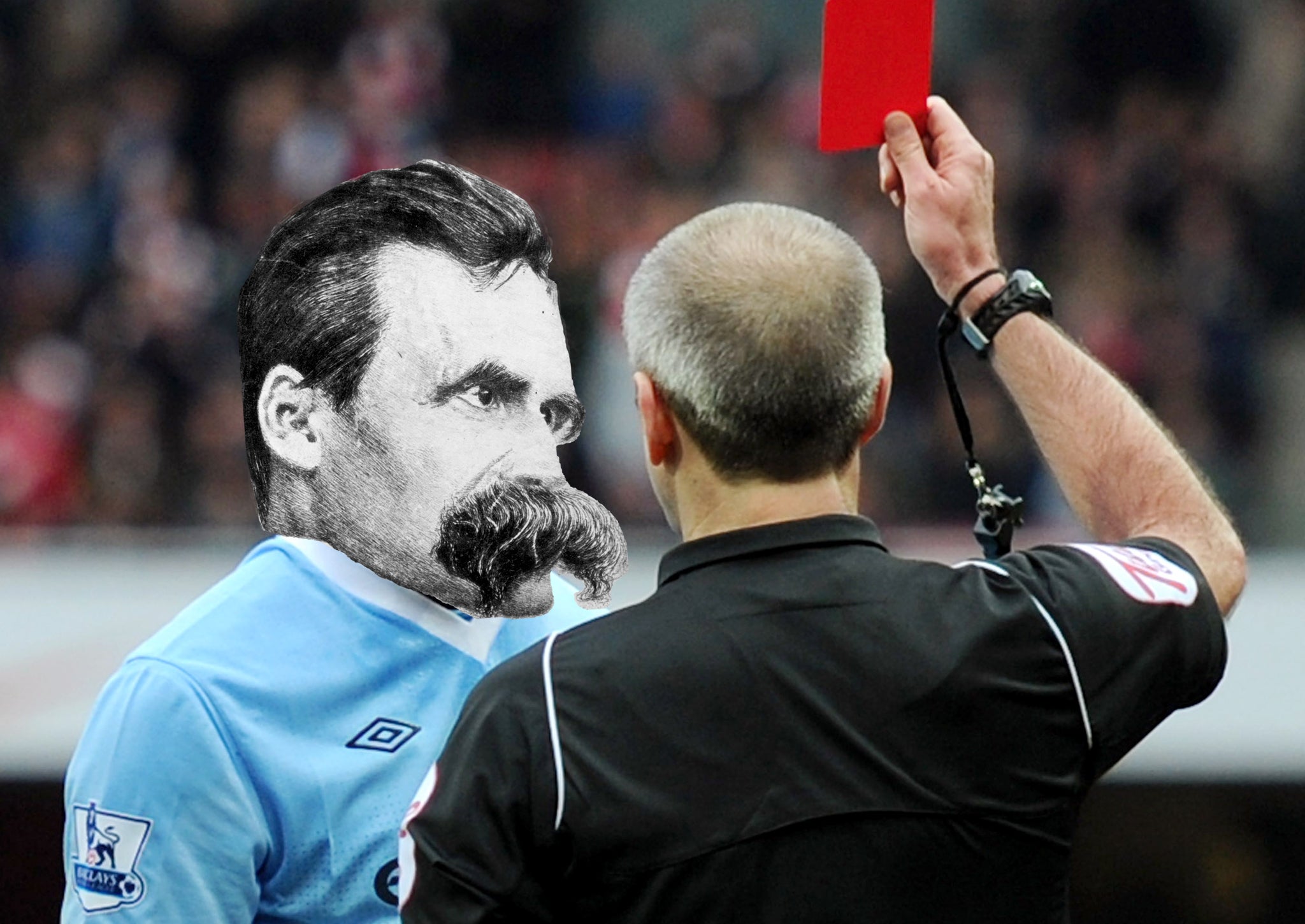

Your support makes all the difference.With the World Cup upon us, this seems a good time to raise the matter of Nietzsche’s sending-off during that ill-tempered football match between Greek and German philosophers in the Olympiastadion at the 1972 Monty Python Munich Olympics.

It’s true that Nietzsche had no business telling the referee, Confucius, that he lacked free will, but to many of the spectators – most of whom, it’s true, would have been German – Confucius was over-hasty in showing him the red card.

And why didn’t the linesman Thomas Aquinas intervene to restore order?

More than 40 years later, Nietzsche’s name has again gone in the book. Though this time it isn’t an inscrutable Chinese philosopher who has sent him off but the Students’ Union of University College London, aka UCLU, not to be confused with UCU, the University and College Union, a Pythonesque teachers’ body which only makes news when it doesn’t ban or boycott something.

One academic body is much like another when it comes to silencing unpopular views: it is an itch that spreads like a contagion from campus to campus.

To be clear – UCLU has not exactly sent Nietzsche off in person, but a university society that bears his name. Which is a bit like allowing Rooney to stay on the field and showing the red card to the Wayne Rooney Fan Club instead. But then what were the Nietzschophiles doing calling themselves a club in the first place? A club! For Nietzsche! The Zarathustrians would have been a better name. Or the Übermenschen. Though I imagine that the latter wouldn’t have gone down all that well with UCLU, either.

“You would not enjoy Nietzsche, sir,” Jeeves advises Bertie Wooster. “He is fundamentally unsound.” A verdict to which Wooster himself readily assents. “Not the sort of thing to spring on a lad with a morning head.” That’s more or less where UCLU stands on the Nietzsche Club, too. Its ideology compounds its morning head.

My own view, when it comes to ideologies, is that if we are to ban one we will have to ban the lot, since they’re all fundamentally unsound. But that’s a side issue. The particular ideologies which UCLU has assumed the right to police comprise the usual daisy chain of racism, homophobia, misogyny, anti-Semitism (unacceptable except in a Zionist context), anti-Marxism, and so on. Anti-Marxism! Did I just say anti-Marxism? As a frequently banned ideology itself, wouldn’t you think Marxism would be reluctant to have anything banned in its name. Ah reader, reader, where have you been these past 100 years?

It’s too obvious to state, but it seems we have to anyway: as a matter of academic principle, no student body has any right proscribing thought. You go to university to read books and, by all means, to refute them but certainly not to blacklist them.

Whoever approaches philosophy and literature with a made-up mind can have little hope of learning from them. No matter that decency is outraged by the practice of homophobia, misogyny, anti-Semitism and the like, intellectually and imaginatively those terms must always be open to question and interpretation.

Society seizes up once it knows to a certainty what it dare and dare not think. Is this not what has been concerning us about schools in Birmingham and Bradford – that brew of superstitious fear and iron conviction of which the only outcome is a closed community? And never mind that it’s to protect society from malign influence that you say you close the gates. The minute you turn the key the malignity is at work.

I don’t say there is nothing to fear from philosophy and literature. We cannot thrill to dangerous ideas while at the same time insisting on their harmlessness. To pursue a thought, however, is not the same as acting on it.

The poet William Butler Yeats could write of an old man’s sick desire brought on by the young in one another’s arms, but that doesn’t make him Jimmy Savile. Lolita might sing a more naked, if cautionary, song of illicit longing, for which reason the censors got out their pencils, but that seems an age ago now, in a dark, dark time, as does the ban on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, a novel once seen as liable to encourage wives and maidservants to copulate as and when and with whom they chose.

It isn’t that we have since decided literature offers no such incitements; it is that we believe we are the better for taking the risk.

As for Nietzsche, he is no more responsible for the Nazis than was Schubert, to whose melancholy melodies SS men went about their business. In fact, he was too restless a philosopher to condone the regimen of any faction: playful, contradictory, more of a poet than a logician, and if he said things some consider racially offensive, the fault lies in those offended. You can’t ask a man to think and put a brake upon his mind.

No Jew sits entirely easily when Nietzsche is in full flow, as no Christian should either. When he begins imagining the Jewish contribution to western culture as “a slave revolt in morals”, an act of “spiritual revenge” on the powerful and high-born out of which Christianity and democracy were born (both pejorative terms for Neitzsche), we quake a little. But ultimately there’s grudging admiration in his findings: an argument against himself. Go somewhere perilous and you don’t know what you’ll find.

If UCLU insists that the Nietzsche Club has a sinister agenda, that it is the members, not the philosopher, whom they fear, then it makes an argument not for banning but for surveillance. We won’t be safe from people who mean us harm by monitoring what they read; we need to monitor them. I don’t doubt that by the logic of the daisy chain Edward Snowden is a hero to UCLU. But if he is, their position lacks consistency. By their own reasoning – else why ban a club? – we need more people being watched, not fewer.

Keep your eye on the ball, Aquinas. You’ve got a flag – use it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments