Nelson Mandela: The man who shaped the new South Africa

The emergence of a stable democracy is due to Nelson Mandela and his principled leadership

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.By the end of the 1980s it was clear that apartheid as a political system would soon end. What no one knew was how it would end – and what would replace it. The end of the Cold War meant that the United States and Britain no longer felt they had to prop up dictatorships – or white power in South Africa. West European countries could now allow a measure of democracy to flourish in the rest of the world. Change was possible not just in former communist countries.

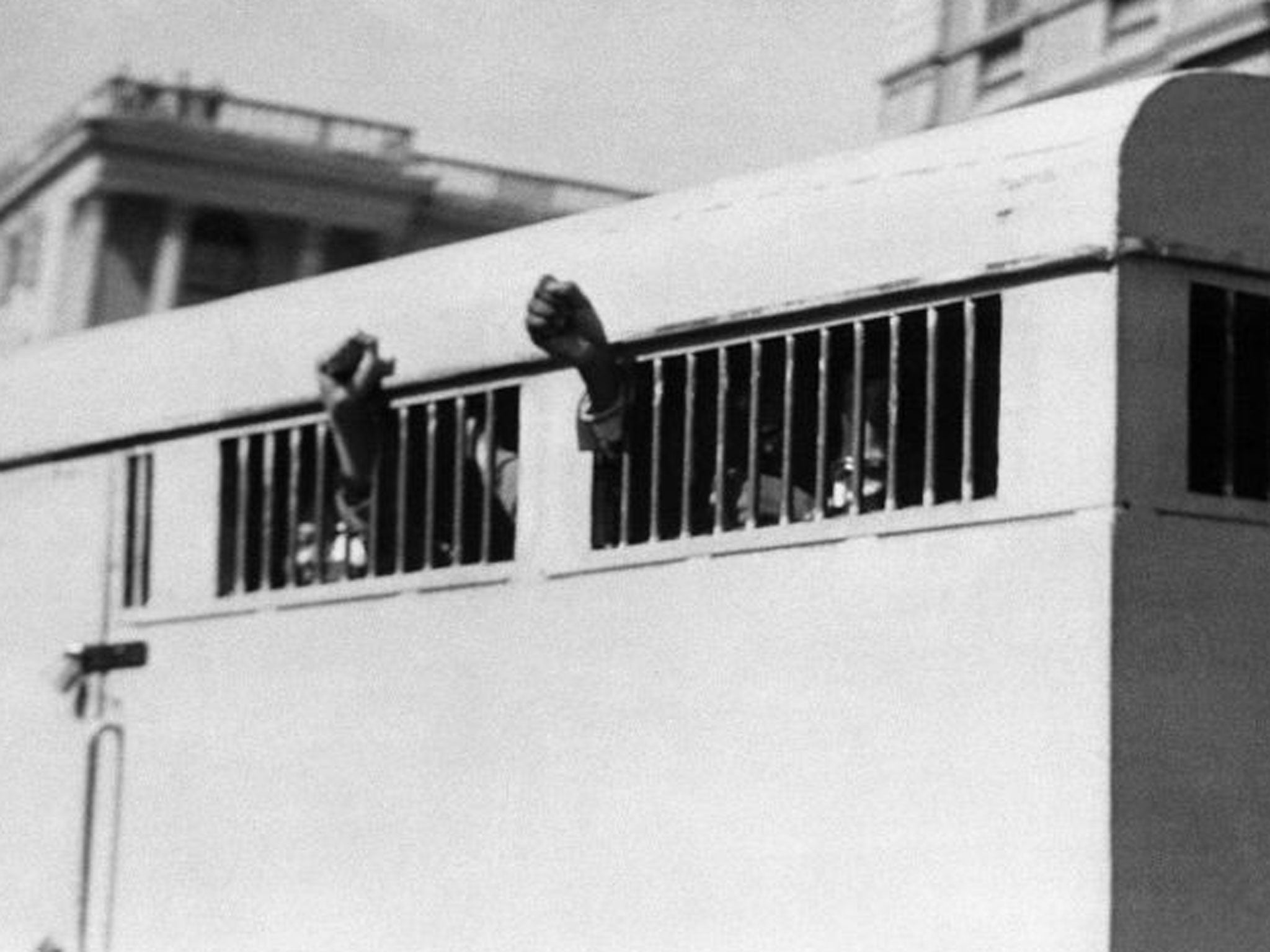

Many people assumed that democracy and majority rule in South Africa would bring chaos and bloodshed. No political organisation was allowed to non-white South Africans except those created by the apartheid state. Crushed by the repression of the early 1960s and dominated by the South African Communist Party (SACP), the African National Congress was unimpressive. Some of its leaders, including Nelson Mandela, were in prison in South Africa. The rest were in exile. At its headquarters in the Zambian capital, Lusaka, journalists were offered interviews with an incoherent alcoholic spokesman, Tom Sabina, who claimed that armed struggle would soon achieve total victory. Its public message was a mishmash of liberal aspirations and violent Marxist slogans. Despite this, the ANC managed to survive, held together by the personal charm of its indefatigable president, Oliver Tambo, and the rigorous, secretive structures of the SACP. Once they trusted you, its leaders would discuss the changes that were taking place in South Africa. But they had no idea how quickly the end of apartheid would come. They were not even close to preparing for government.

No one knew what Nelson Mandela was like. When news reached the ANC's exiled leaders in the late 1980s that he had talked with senior representatives of the apartheid government and even met P W Botha, they panicked. Under the ANC's rigid rules, he had not been authorised to do that. There were fears that Mandela had been turned while he was in jail. Senior ANC members started to brief the press to prepare them for the dumping of Mandela. Frene Ginwala, later Speaker of the Parliament, and Aziz Pahad, who became Deputy Foreign Minister, began to lay the groundwork, saying: "We just don't know what they have been giving him … He's an old man and has been in prison for a long time... He may not quite understand …"

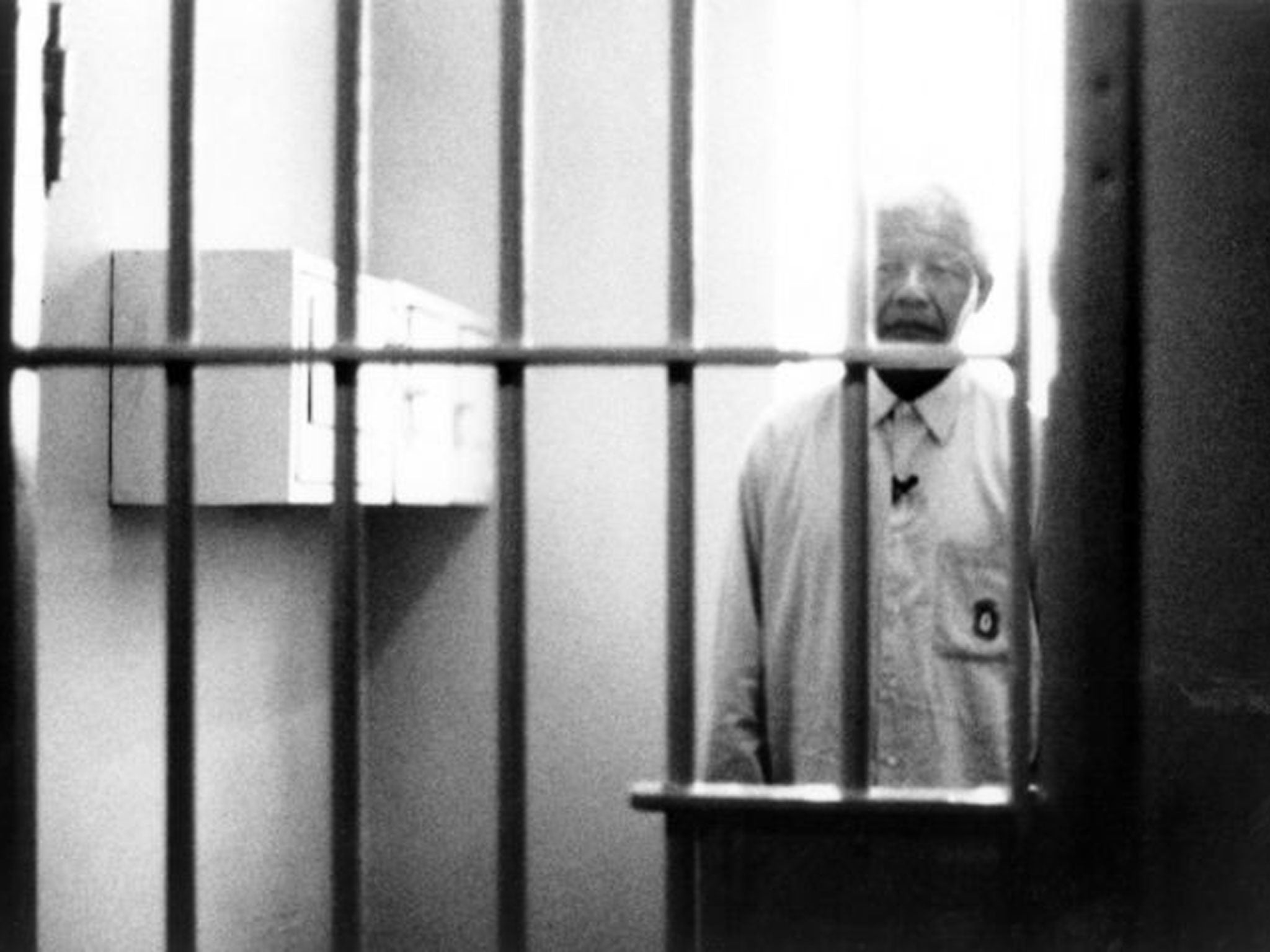

Their fears were groundless. Looking back, it is impossible to imagine the end of apartheid and the birth of the new South Africa without Mandela. He was seen as the hinge on which transition turned. Historians will find it hard to disentangle the economic and political inevitability of apartheid's collapse from the personal mission of its remarkable new president. At a distance, the two merge in a glorious moment of fairytale history.

Jail had strengthened and matured Mandela. More importantly for the exiled ANC, he had remained firmly within the ideology and policy of the party, describing himself as its humble servant. He had not done or said anything of political importance that the movement had not sanctioned. But, ironically, locked up and deprived of news, he saw further than the exiled leaders of the ANC living in Lusaka and London. And he still believed the rhetoric of the Freedom Charter: "that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white … that only a democratic state, based on the will of the people, can secure to all their birthright without distinction of colour, race, sex or creed."

Mandela's impact on the world was immense. The passionate re-assertion of the fundamental principles of human civilisation by a merry old black man imprisoned for 27 years for being black was like the rediscovery of childhood innocence and happiness. In South Africa, those principles became the foundation of the world's most liberal constitution. In the rest of Africa, however, the impact was less certain. To other African rulers, Mandela's belief in freedom, democracy and justice sounded like something from another planet.

Until the beginning of the 1990s there were only two nominal multi-party democracies on the continent: Botswana and Gambia. Most African countries were one-party states ruled by dictators, many of them military. Opposition was not tolerated. But to Britain, France and the US, Mandela and the new South Africa gave hope for the rest of Africa. The continent could be taken seriously.

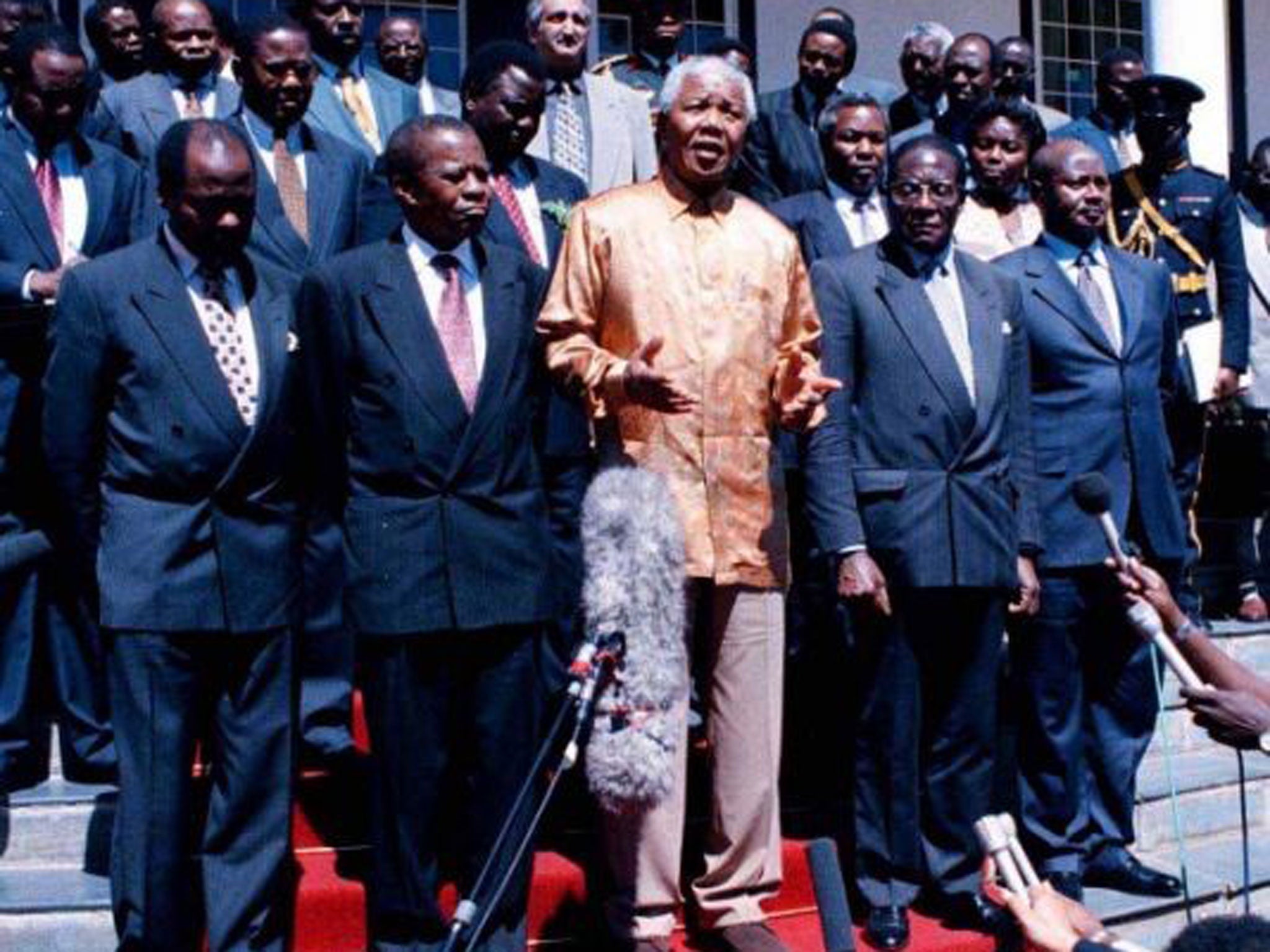

Mandela also gave hope to ordinary people in Africa. Wherever he went, he was greeted by cheering and dancing crowds. But he did not explicitly promote an agenda of freedom and democracy on these early journeys. Most of the visits were to thank African rulers for the support they had given the ANC during the struggle.

Although many of these leaders were themselves unrepentant old dictators, Mandela was always very careful not to criticise the governments of countries he visited, especially when, like Libya, they had helped the ANC. If asked about the human rights situation in a particular African country, he would smile and say that he had been away for a while and was not well-informed about latest developments. This was disingenuous but smart. He wanted to meet everyone, even if they were crooks or murderers. But the point was not missed. The words he used; freedom, rights, justice, caused many African dictators to pause and look over their shoulders. After all, he had talked to the most evil regime on the planet; nothing would be lost by a handshake and a few words. But many African opposition activists who had suffered in jail pointed out that Mandela would not have survived 27 years if he had been jailed in their countries.

During white rule in South Africa, the ANC and its supporters argued that Africa's poverty was the result of apartheid. Africa could begin to develop only once South Africa's industrial energy could be put to use for the benefit of the whole continent. At one level, it was true; Africa's biggest economy was cut off from all but its immediate neighbours. But it was clearly nonsense to blame hunger in Ethiopia on South Africa's race laws. At a deeper level, one legacy of colonialism has been a lack of self-belief, belief in Africa, Africans' ability and African institutions. "This is a wonderful country, the only problem is that it is run by Africans" has been a distressingly common sentiment across Africa. Nelson Mandela changed that. His dignity, self-belief and refusal to become a victim inspired millions of people, especially Africans. Here was a role model for any black people facing oppression. He renewed Africa's pride in itself.

When the ANC came to power, the big question for South Africa was whether it would embrace or remain separate from the rest of the continent. Its economy worked well but needed foreign investment. But foreign investors were put off by Africa's image of inefficiency, instability and corruption. So it made economic sense for the new South Africa to maintain a discreet distance from the rest of Africa. But would Mandela's government show solidarity with the continent or follow its self-interest?

It was not even a question for Mandela. He committed South Africa to being totally African. But where African rulers demanded solidarity against the "West" by asserting undefined "African values", Mandela preached universal values: freedom of speech, human rights and democracy. The continent's dictators had oppressed their people, claiming their rule was the "African way", and fended off criticism from the rest of the world by claiming it was neo-colonialist or racist interference in their internal affairs. The formula worked well, especially against former colonial powers. Mandela was careful not to condemn African rulers, but he began to undermine that defence with his call for universal human rights and freedoms.

Thus, South Africa came to have one of the most liberal constitutions in the world, making it as different from the rest of Africa as the old South Africa had been – but this time in the opposite direction. The new constitution enshrined rights for women and gays. In much of the rest of Africa, women are expected to stay at home and defer to men. Women's rights are a joke and gay rights unmentionable – in many African states homosexuality is a crime. Mandela's support for law and personal freedom flew in the face of many African customs and attitudes. He may have committed South Africa to Africa but it remained a very different country to the rest of the continent.

It was a difficult path to tread. South Africa's immense economic, political and military power could not but influence the rest of the continent. Yet the ANC government, deeply conscious that South Africa had bullied its neighbours in the past, did not want to use coercion again, even in the cause of its liberal values. Somehow it had to turn from a malign to a benign giant. But how? Mandela's principle was that if he could talk to the apartheid regime, he could talk to anybody. He approached people with an assumption of goodwill and emphasised forgiveness and reconciliation. Power sharing – even with evil murderers – was acceptable politically if it brought peace. Immediately after his release, for example, he upset the West by trying to heal the rift between Libya and the West over the Lockerbie bombing. He sought to have the men convicted of the bombing brought back to Libya and showed sympathy for them as imprisoned individuals. It was one of his few direct foreign policy successes.

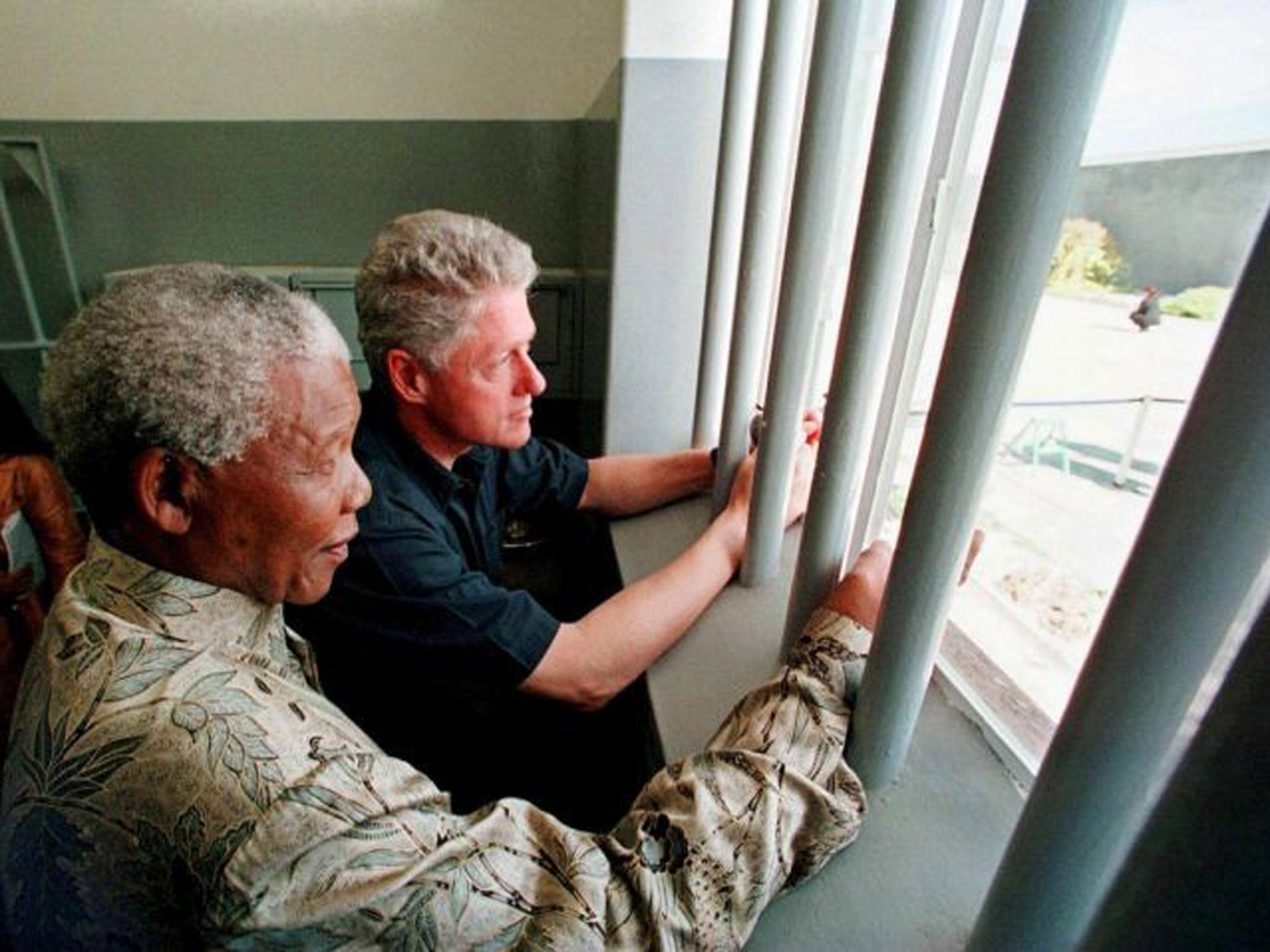

Mandela demonstrated that he was not afraid to upset Western governments in his statements of solidarity with the rest of Africa. At one level, there seemed to be a common interest in making peace. Western countries were keen for Mandela and South Africa to sort out Africa on their behalf. "African solutions to African problems," a phrase that came from the Clinton administration, seemed to fulfil Africans' ambitions to be masters of their own fate. But it was in part a cynical ploy of the West to wash its hands of Africa.

The Americans and British, and to a lesser extent the French, hoped that South Africa would become the policeman of the continent on their behalf. That was the last thing South Africa wanted; to be seen as the cat's paw of the West in Africa.

In 2000, Mandela threw South Africa's weight behind the plan to replace the Organisation of African Unity with the African Union. Given a wider and deeper mandate than its predecessor, the AU charter commits Africa to the principles of democracy and respect for human rights. Most importantly, the principle of intervention under certain circumstances replaced the principle of non-interference.

Mandela was also keen to get involved in making peace directly in Africa. But he would often make up foreign policy over the phone as he went along. As he got older, he sometimes forgot to brief his officials on what he had said.

Right from the start, Africa's ecstasy and agony confronted the new government. In 1994, against all predictions, as South Africa's first democratic election passed off peacefully and brought Mandela to power, hundreds of thousands of people were being murdered in Rwanda in the world's fastest genocide. Mandela later apologised for not doing more at the time, but it would have been hard to break off the party. He tried to make up for it by taking the lead in the Burundi peace process. It was a long, tortuous road and the Burundians showed no particular respect for Mandela. Only 10 years later was there an election and the beginnings of peace.

Under Mandela, South Africa took the political lead in other African crises, too. In 1996, Congo – then Zaire – was in crisis and Mandela tried to broker peace between President Mobutu Sese Seko and the rebels headed by Laurent Kabila and backed by Rwanda and Uganda. He did not succeed. Kabila and his allies also rebuffed his attempts at a power-sharing agreement and pressed on to take the whole country.

In 1995, when the Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha hanged Ken Saro Wiwa in the middle of a Commonwealth conference, Mandela was outraged. Nigeria's Foreign Minister hit back, saying Mandela could not be trusted, calling him "the black president of a white state". That was the first time someone had insulted Mandela in such a way, but the Nigerians got away with it. Mandela's magisterial condemnation of Saro Wiwa's judicial murder was thrown back in his face.

In 1998, Mandela sent the South African army into the tiny state of Lesotho, landlocked by South Africa, when an election ended in violence. Embarrassingly, it encountered unexpected resistance from the Lesotho army and suffered casualties before order was restored. But it began to be clear that when it came down to realpolitik, the new South Africa might be no more popular than the old South Africa.

Robert Mugabe gave Mandela the most grief. His party, the Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu), had been aligned to the Pan Africanist Congress, the ANC's South African rival, with the ANC aligned to Mugabe's rival, the Zimbabwe African Patriotic Union. This mattered. Even after independence, the abstruse but internecine infighting between the liberation movements continued. During apartheid, Mugabe had been chairman of the Frontline States, the alliance of southern African countries fending off South Africa's attacks in the region. With the end of apartheid, his role was redundant. Both politically and personally, Mugabe felt marginalised. Beside Mandela, he began to sound bitter and outdated.

In 1998, Mandela was involved in Congo again. Mugabe led an alliance of southern African states to protect President Kabila from rebels backed by Uganda and Rwanda. This was, in the words of Madeleine Albright, Africa's first world war. South Africa vigorously opposed the move but Mandela was outmanoeuvred and forced to support it. It was a personal and political public humiliation for Mandela. An aide recalls taking a call from Mugabe and Mandela, head in hands, saying: "Please don't tell me I have to talk to Comrade Mugabe again."

If Mandela's Africa diplomacy was sometimes thwarted, South Africa's new commercial activities in the rest of the continent were often rejected outright. Held back by the boycotts in the apartheid era, South African businesses and transnational corporations burst into action as soon as apartheid was declared dead. They sold cheap South African goods and bought up local businesses. Their impact on the region's economies was not always benign and they were regarded as arrogant and domineering. But they have persisted and are far more prepared to work in zones of political instability than their European or American counterparts.

So the new South Africa under Nelson Mandela was not always the bridge that linked Africa to the rest of the world. Both politically and commercially, it was often perceived as a wolf in sheep's clothing: politically a tool of Western governments, commercially gobbling up African businesses or starving them to death by undercutting their prices. While Mandela was a great African hero to ordinary Africans, to many African politicians he was just another interfering and powerful African ruler to be outmanoeuvred.

Richard Dowden is director of the Royal African Society

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments