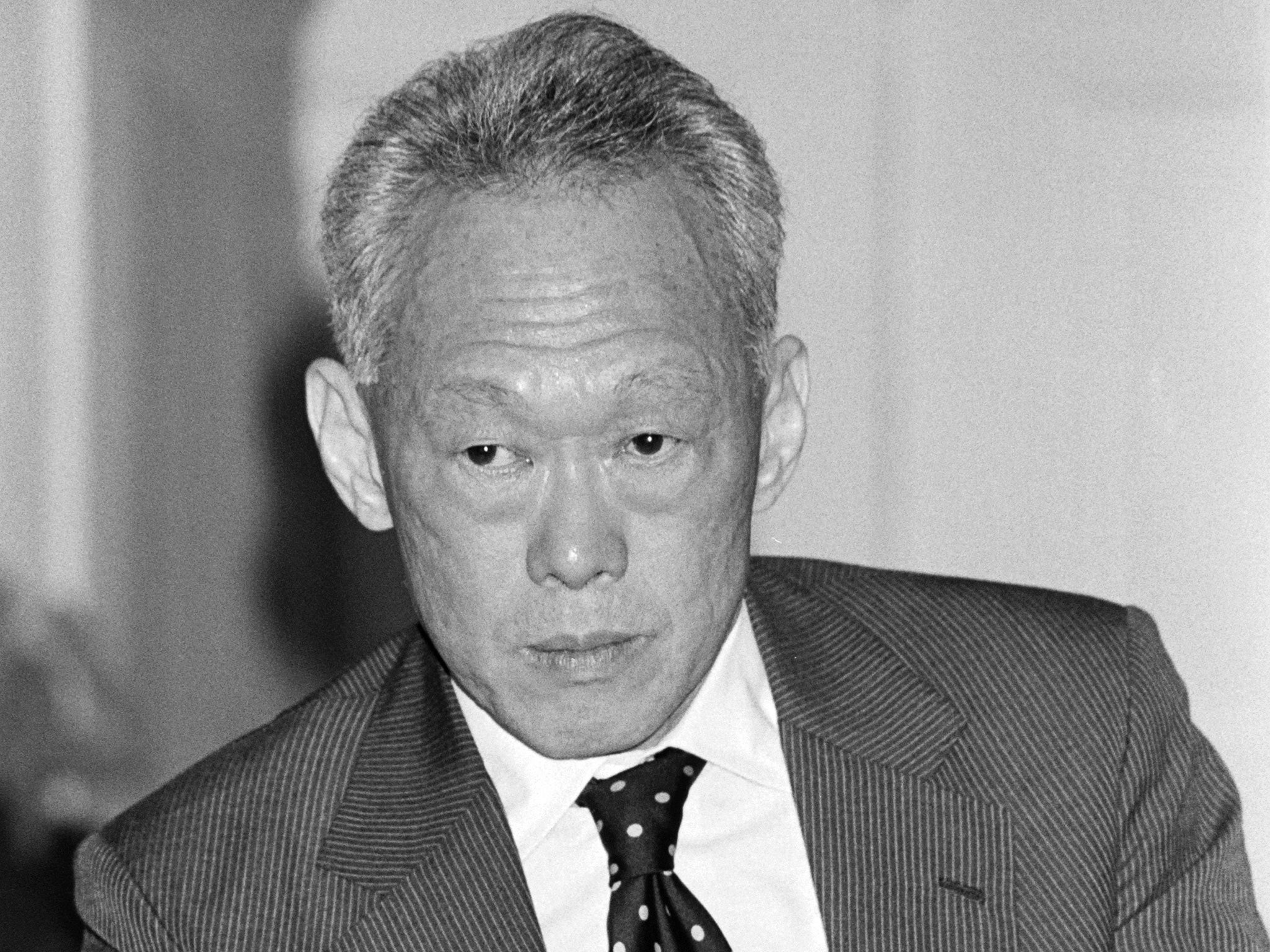

Lee Kuan Yew: An entirely exceptional leader who balanced authoritarianism with pragmatism

Modern Singapore was his creation and he was immensely proud of it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I went to stay with a relative in Singapore in the mid-1980s, I marvelled at the fact that the charming old colonial house he was renting had survived intact, surrounded by the booming city state’s office towers. Simple, he explained: the owner of the land it stood on was at school with Lee Kuan Yew, and had made the grave mistake of bullying the little fellow. He had wanted to knock the house down and build something more profitable for years, but for some reason planning permission was always refused.

For Lee Kuan Yew the personal was intensely political and vice-versa: modern Singapore was his creation, he was immensely proud of it, and for half a century he was not merely the city-state’s prime minister but also its unquestioned boss. If he was not above taking revenge on a childhood enemy, in other respects he was a model ruler – an uncrowned, secular king, duly succeeded to the throne by his son.

Overseas Chinese had made fortunes and established business dynasties across south-east Asia under the protection of the colonial powers, but once independence arrived their differences from the majority populations – of ethnicity, language and customs as well as wealth – often inhibited them from seeking the political power to which their financial clout and business skills would otherwise have opened the door. Singapore, so small, so strategically located, was the exception that proved that rule, and Lee Kuan Yew turned out to be an entirely exceptional leader. Singapore’s break with Malaysia in 1965, six years after he came to power, was “a moment of anguish”, he later said, but it was also the making of the city-state, and of his own political pre-eminence.

Poised on the Malacca Strait which controls sea trade between south and east Asia, Singapore was one of those colonial possessions, like Aden and Hong Kong, that were brought into being by the imperatives of the maritime trading empire, and in his style of rule Lee was the inspired successor to the British: balancing authoritarianism with pragmatism; committed, like the British colonial government, to the rule of law but with no interest in complicating matters by introducing real democracy; lacking the racial or religious chauvinism that plagued other Asian territories after independence, so the Malays, Indians and other non-Chinese Singaporeans continued to prosper under his rule without having to worry about political or religious persecution.

Just as remarkable was Lee’s freedom from the taint of corruption, and he succeeded in imposing a high standard of morality on the territory. Deng Xiaoping was doubtless inspired by Lee’s achievement when he turned the attention of the People’s Republic to capitalism, but the mainland’s failure to digest Lee’s lesson about corruption has created immense problems to which President X Jinping is desperately seeking solutions.

Singapore’s success has been a beacon to other maritime entities like Qatar and Abu Dhabi: proof that pocket size plus strategic location is potentially a recipe for post-colonial success, if shrewdly (and undemocratically) managed. If those statelets also share with Singapore a certain deracinated dullness, a lack of genuine cultural vigour – compared with dynamic, rackety Hong Kong, Singapore was always a bore – that is probably part of the package.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments