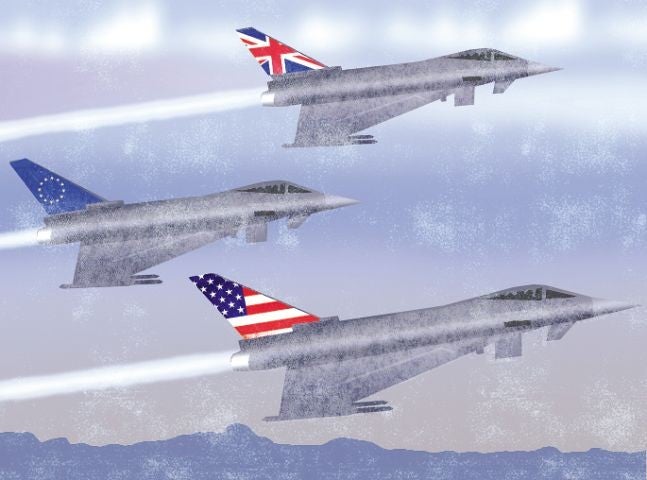

Learn from the errors of the Westland Affair and let the Europeans come to our defence

Yet again, when Britain is forced to choose between a special relationship with America and cultural affinity with Europe, it chooses dithering and delay instead

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This time next week, the whole landscape of the global defence and aviation sector may look different. Or it may not. The choice rests with Britain. For at least the third time in as many decades, the UK faces a choice between its “special relationship” with the United States and its geographical and cultural affinity with Europe. Once again, it is dithering, abjectly, as a prelude, quite probably, to doing the wrong thing.

For several weeks now, the British defence conglomerate, BAE Systems, has been talking to the European aviation giant, EADS, with a view to what the British – naturally enough – describe as a merger and their negotiating partners have generally been too kind to call a takeover. Under the terms, such as they have become public, BAE would take 40 per cent of the new company, while EADS would have 60 per cent. The UK Takeover Panel has set next Wednesday, 10 October, as the deadline for the two sides to publish formal proposals or abandon the project.

If the arguing in private bears any relation to the public fight – and all the signs are that it is even fiercer – the deadline may be extended, despite misgivings all round. Whether it is or not, the shadows are crowding in on a deal that appeared to be cruising to acceptance, and they seem to be growing darker by the day.

Ever since news of the talks leaked last month, it has suited the main parties to present the proposed merger as just a commercial proposition. And the arguments in favour are not hard to understand. BAE is primarily a defence contractor, at a time when government defence budgets are in decline. With the financial crisis dictating cost-cutting everywhere, the withdrawal from Iraq complete and disengagement from Afghanistan set for 2014, the world’s largest market for advanced military equipment is contracting. The rise of China is also precipitating what has been termed a “pivot” in US defence policy, away from Europe and land warfare and towards maritime competition in East Asia. The configuration of US defence spending is changing.

So unless it is to accept a drastic contraction itself, BAE needs to diversify. EADS is seen – by the two chief executives, Ian King for BAE and Tom Enders for EADS – as the perfect partner, with Airbus the jewel in its crown. A case can be made that the two businesses are complementary. BAE brings its strength in defence, a number of “special security agreements” that have allowed it to participate in sensitive areas of the US defence industry, and privileged access to the US market. EADS brings its success in civilian aviation, and the two markets – so the argument goes – tend to rise and fall at different times.

There are counter-arguments on the business front, of course. One is that a merger would cost jobs, and probably a disproportionate number of British jobs, because labour protection in Britain is weaker than on the Continent. Another is that US defence cuts will not leave as many openings for outsiders – even privileged outsiders – as the Europeans hope.

Such considerations, however, are far outweighed by the political concerns they conveniently cloak. The Americans, while boasting of their open market, routinely cite security reasons for closing it. China has just launched a lawsuit against the US for rejecting its investment in wind farms, and Dubai ran into difficulty over ports. A question mark thus hangs over the “special security agreements” that have been BAE’s key to the United States. Washington, already being lobbied by BAE’s home-grown rivals, is hinting that it would be uncomfortable advancing such privileges to a company with a majority EU holding – which is a polite way of saying it does not trust the French. BAE, for its part, says that if the merger with EADS costs it the special security agreements, the deal is off; full stop.

This is by no means the only political spectre at what is still far from a feast. Franco-German rivalry comes into it, with a minor squabble over the site of the European headquarters – Toulouse or Munich – and major differences over corporate structures and government involvement that have been brought to a head by the prospect of incorporating BAE. Enders hopes that a merger with BAE would entail the British, French and German governments each taking a “golden share”, while ending interference by ministers trying to defend sectional or national interests.

Enders wants the combined company to be run as a commercial undertaking. But what all the arguing underlines is that the defence industry has never been, and perhaps can never be, purely commercial. Profound national sensitivities always enter the equation, too.

Which brings us back to the UK. The Prime Minister was said to be relaxed about the proposed merger, even favourable. The trade unions have also been quiescent – so far – eying opportunities rather than lost jobs. Others, though, are hostile, and they include the same people that David Cameron is already having trouble with on the right wing of his party. They fear job losses; they fear the submersion of a great British company in a European conglomerate; they worry about national sovereignty. All these, though, cloak their central fear of a definitive tilt away from the “special” transatlantic relationship and towards a European defence alliance.

We have been here before, of course. In 1986, Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet split over the future of the Westland helicopter company and a furious Michael Heseltine resigned when the European option was rejected. Essentially, the same choice was made in 2006, when BAE sold its 20 per cent stake in Airbus to EADS to focus on the US defence market. And unless the BAE-EADS merger proceeds – which would go a long way towards reversing that 2006 decision – we are going to be here in another few years, with arguments about the renewal of the Trident nuclear deterrent, the totem of the UK-US special defence relationship.

Time and again, the UK – or, rather, stubbornly nostalgic sections of its political, business and media classes – simply refuse to recognise reality. Every time the Government has preferred the transatlantic over the European option, the result has been failure, with the – expensive – choice having to be revisited or reversed. The plan for a BAE-EADS merger offers Britain its latest opportunity to cease being a defence vassal of the US and show its commitment to a future in Europe. Putting it as baldly as that, though, almost guarantees that yet another historic chance will be missed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments