In the Tower of Babel that is Twitter, silence descends. Quite right, too

Tweeters used to shrug and say, "Well that's just the internet", but Lord McAlpine's solicitors may have just changed Twitter for ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

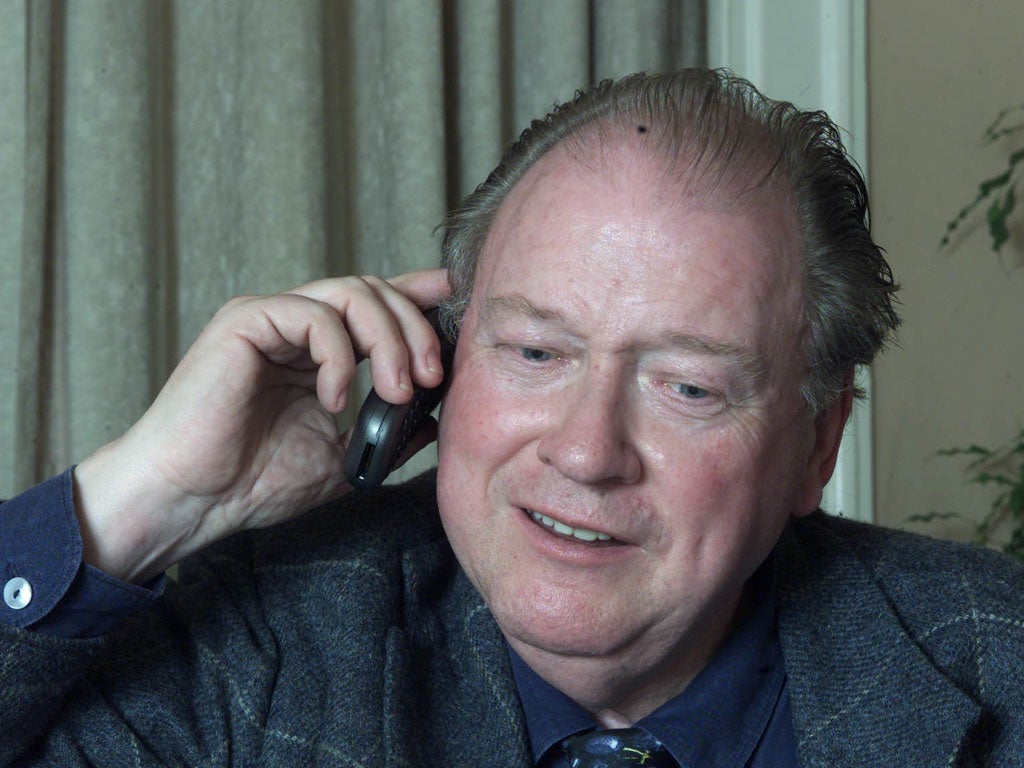

Your support makes all the difference.As news of poor, wronged Lord McAlpine’s £185,000 payout by the BBC – and his legal firm’s intention to pursue every single Twitter user who slandered him – played out on respected news channels this Thursday, the most curious thing descended over my favourite social network: a kind of hush.

OK, aside from the odd muted grumble about wealthy McAlpine becoming ever wealthier, and the odd meek musing on how he could donate his windfall to Children in Need. But otherwise Twitter seemed to be washing its hair. How strange? This news item ticked every box on the instant Twitter brouhaha checklist: the BBC, “fat cats”, the licence fee, sex allegations, the headiness of Sally Bercow, the pompousness of George Monbiot, freedom of speech and so on.

I’ve been a Twitter user for five years. I know how these things work. But where were the “Twitchfork mobs” now? Or those brave internet “publish-and-be-damned” warriors? Where were those delightful living-in their-mother’s-box-bedroom trolls? Or the amateur Radio 4 comedy writers, or the frothy-mouthed freedom-of-speech defenders? In internet parlance, they’d thought WTF and decided to STFU.

Andrew Reid, Lord McAlpine’s solicitor, may well have changed the face of Twitter for ever. Reid has said that a team of experts has collated any offending Twitter messages on McAlpine – including tweets, retweets and deleted tweets – and plans to pursue every single person involved. “Let it be a lesson,” he said, “to everybody that trial by Twitter or trial by the internet is a very nasty way of hurting people unnecessarily and it will cost people a lot of money.”

To me, Reid’s words felt like a social networking game-changer because – and wishing to sound the opposite of glib here – Reid actually sounded like he had a grip on that which he was spouting off about. Like he’d actually set eyes on a Twitter homepage, or had even sent a tweet, or was at least employing bright young things who had.

Until this week, legal threats against Twitter – for example, during the Ryan Giggs/Imogen Thomas superinjunction case – have had the risible feel of King Canute shouting at the sea. Shutting up Twitter seemed like a pipe dream. The matter was too big, too confusing, too brimming with arduous uncharted legal territory. And more than this, Twitter is the home and the weapon of choice of the educated troublemaker.

When Sally Bercow (58,000 followers) simply tweeted McAlpine’s name “mischievously” at a time when his name had become a trending topic, she clearly believed she was on safe ground. Same, too, for Iain Overton, managing editor of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which jointly produced the Newsnight report, who tweeted, “If all goes well we’ve got a Newsnight out tonight about a very senior political figure who is a paedophile.”

But then here comes Reid intending to open a can of old-school legal whoop ass on this brave, fresh, new technology. Reid sounded heavily briefed, ninja-focused, and was, that day, in the process of successfully extracting £185k from the BBC, not for saying McAlpine’s name, but for fanning flames which led to people tweeting his name.

Reid sees everyone who flocked to the scene pitching in flippant 140-character jokes, titbits and unfounded grot as part of the problem. “Twitter is not just a closed coffee shop among friends. It goes out to hundreds of thousands of people and you must take responsibility for it.” He added: “It is not a place where you can gossip and say things with impunity, and we are about to demonstrate that.” To me, this sounded like the piano in my favourite cyber speakeasy having the lid slammed firmly shut.

Is this the death of the Twitchfork trial? What McAlpine has suffered – regardless of the severity of the allegation made against him – has been until now a pretty standard Twitter process. Trial by Twitter happens to people, famous and non-famous, brands and businesses every single day, equally vicious and anger-making, for the most flippant and throwaway of reasons. From my experience, columnists and writers get it a lot. It feels like being in a schoolyard and the school bully punching your face in and the world putting down its lunches and running, chortling and howling, trying to join in.

Typically, when I watch other people getting the drubbing, the rumpus begins with a nugget of information displeasing someone. For example, “Have you heard what Tulisa said on This Morning?” “Have you heard that this bus company refused a pregnant woman a seat?” The “facts” about the case will be trumpeted, initially by tweeters who only have a few followers, then eventually retweeted by tweeters with thousands of followers, before a wildfire of incandescent rage over something very little takes hold.

Quickly the Twitter timeline gets clogged with abuse, jokes, attempts at debate, attempts to defend the person/company/ incident and thousands of abusive tweets being sent to the relevant Twitter account. The key words become a trending topic. More tweeters gather, confused and excited. Some tweeters will suggest, “Um, this is maybe slightly illegal?”, to be shot down furiously from the freedom-of-speech warriors.

And then the blogs begin, roughly cobbled together blogs, which will offer a great personal insight into the incident, typically without fact-checking anything that occurred. The blog will be tweeted; counter-blogs will appear and then threads on the Mumsnet messageboard and a dozen other open message-boards full of opinions on the very shonky facts. After about five days, a whole new set of late adopters will begin noticing the story, which leads to a constant trickle of abuse. It’s like being trapped in an echo chamber. And until now, most Tweeters would shrug and say, “Well that’s just the internet.” I have a feeling Andrew Reid might disagree.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments